During my current expedition through Wallacea I’ll be spending a lot of time on Sulawesi. I’ve already seen Bira, on the southern coast, as well as the Maros region. I’ve also spent a lot of time in Makassar, the capital and largest city in eastern Indonesia — a bit too much, to be honest, but the jeep is a fickle beast (more on this in an upcoming post). I’ll be spending the rest of August and most of September on the island, exploring the many wonders in Central and North Sulawesi.

By the end of September, though, my goal is to ferry the jeep from North Sulawesi to Ternate, the gateway to North Maluku. Like Wallace, I intend to use this as a base to explore the nearby islands of Halmahera and Bacan — some of the most interesting locations Wallace visited during his travels in the Malay Archipelago. It is here that you can truly see the complex intermingling of Asian and Australasian animal species characteristic of Wallacea. The first bird of paradise species you encounter moving eastward in the archipelago, for instance, makes its appearance in North Maluku — Wallace’s standardwing.

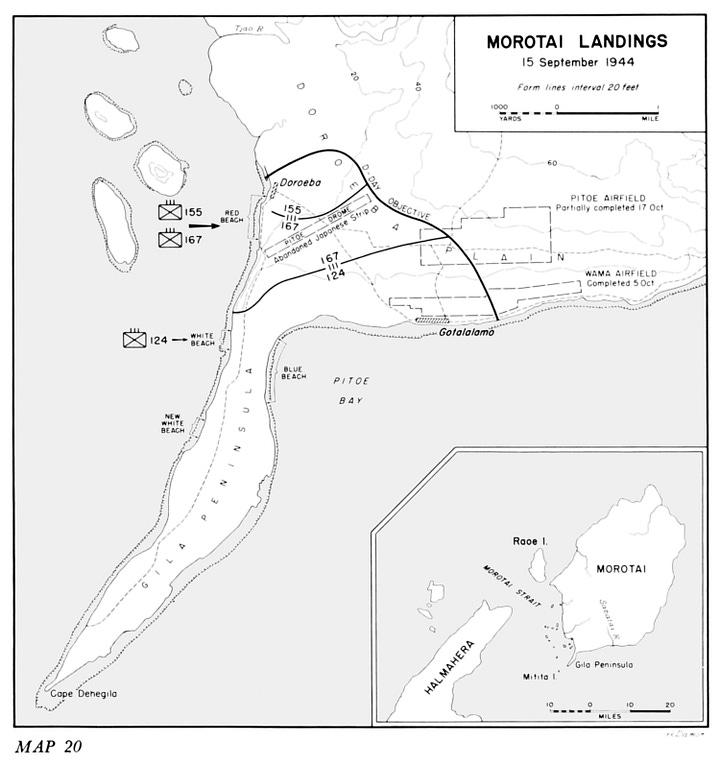

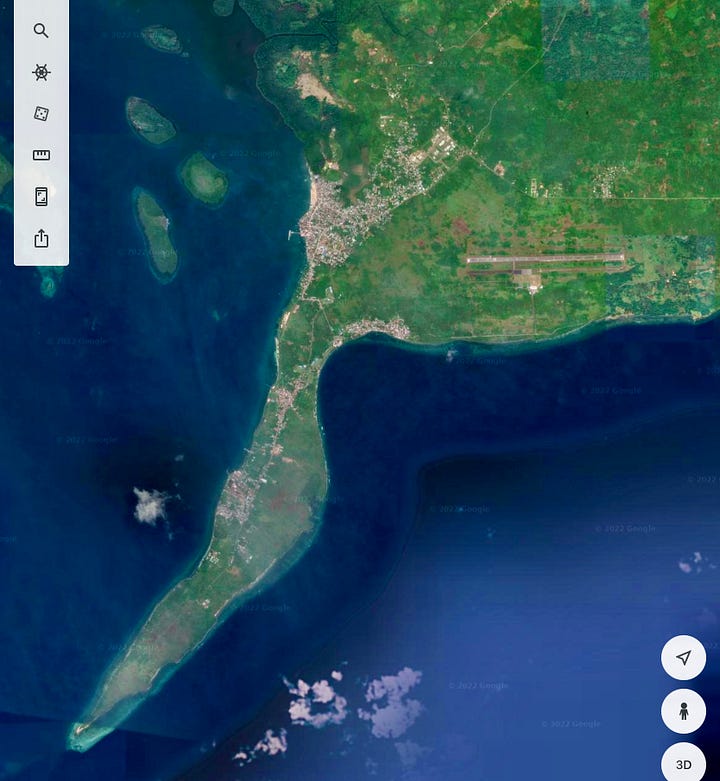

In planning this part of the trip, I’ve been interested in how far I could push my exploration of the islands surrounding Halmahera. Morotai is on the list, in large part because of its role in the Second World War, when MacArthur’s forces used it as a base for the final assault on the Japanese-held Philippines. On Google Earth you can still see the remains of the Allied runways running parallel the present-day airstrip, just to the east of the small town of Daruba, and there are several boat and plane wrecks dating from the 1944 invasion in the shallow waters off the coast that should make for some interesting diving. It was even the location of the last Japanese surrender of the war, in 1974 — five years after I was born. The story is fascinating.

Looking into the islands to the south, though, yielded a surprise. The Obi Islands are about as far off the beaten path as you can get in Indonesia — far beyond what’s covered in Lonely Planet or a Bradt Guide. There are a couple of helpful websites, though, and one of them included this ominous description of Bisa Island:

Also known as “Snake Island” because of its healthy population of Death Adders, visitor’s will likely tread wearily as they explore Bisa.

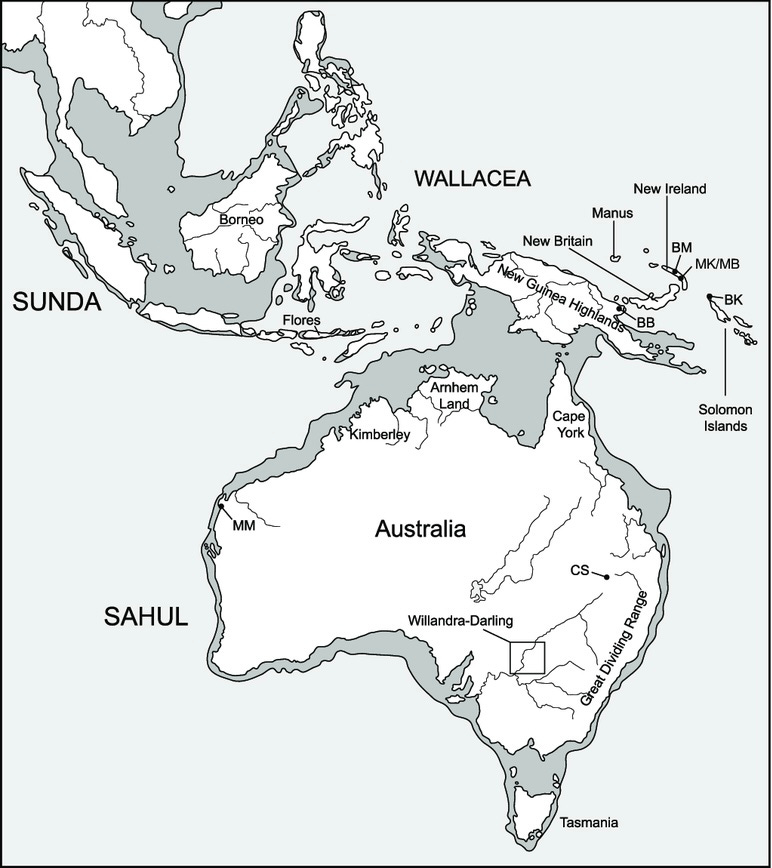

Death Adders? I’ve always thought of this as an Australian species, so I was surprised to learn that there is a ‘healthy population’ (‘unhealthy’ would perhaps be a better description for visitors, given that these are among the most dangerous snakes in the world) on tiny Bisa Island, especially as they aren’t found on nearby Bacan or Halmahera. I did some digging and found a Death Adder distribution map, confirming my sense that this is basically an Australian species, with a range that extends into nearby New Guinea — also part of the Australasian biogeographical region.

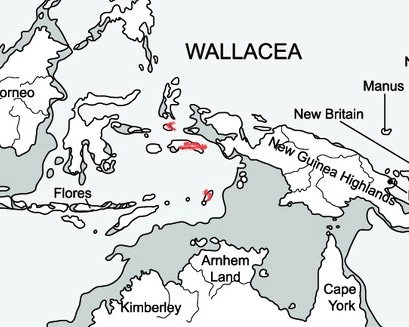

Zooming in, you can see the oddity of finding Death Adders on Obi and Bisa islands, but not Halmahera:

It’s quite easy to explain Death Adders in New Guinea. As with Sunda — the landmass created during the last glacial maximum joining Sumatra, Java and Borneo to mainland Southeast Asia — the island of New Guinea was once joined to Australia in a landmass known as Sahul. During the last ice age, sea levels were over 100m lower than today, creating land bridges between the present-day islands of the region. New Guinea was connected to the Cape York Peninsula and Arnhem Land, allowing easy movement between the two for thousands of years. This has been a regular occurrence throughout the Pleistocene as ice ages have ebbed and flowed, allowing for the dispersal of a variety of species — including Death Adders. The Aru Islands south of the Bird’s Head Peninsula in western New Guinea were also part of Sahul during these periods, explaining the presence of the snakes there. The enigmatic Australasian fauna of the Aru Islands — particularly the spectacular greater bird of paradise — actually inspired Wallace to interrupt his two stints in South Sulawesi in 1856-1857 with a six-month visit to the remote islands.

What does this tell us about the spread of Death Adders westward into Wallacea? We’re left with three island groups where the snakes are found today that were never connected to Sahul: the Obi Islands (including Bisa) in North Maluku, Seram (and nearby Ambon) in Central Maluku, and the Tanimbar Islands in southern Maluku. All have remained disconnected from the larger continental landmasses of Sunda and Sahul throughout the Pleistocene.

The tectonic structure of this region of Indonesia is the most complicated in the world, with a dozen or so tectonic plates and fault zones twisting, thrusting and sliding around each other. Sulawesi is a relatively young island, pushed upward out of the ocean only in the past 15 million years. Halmahera is roughly the same age, while Obi and Bisa seem to date to the past 2-3 million years. Despite the tectonic whirlwind in the region, though, all of the islands were in roughly the same location they are today for at least the past 15-20 million years: they didn’t detach from Sahul recently, carrying Death Vipers with them on their tectonic journey.

This leaves one final possibility to explain how the Death Vipers reached Snake Island: they were carried there from Sahul over water, most likely from the westernmost part of the Bird’s Head Peninsula, given the prevailing currents due to the Indonesian Throughflow. During the violent tropical storms that are relatively common in the region, wind and heavy rain can wash trees and undergrowth out into the deeper water where they form rafts that can then be carried long distances with terrestrial stowaways like insects, snakes and small mammals. I’ve visited the Raja Ampat region in the northwestern part of the Bird’s Head — renowned for its spectacular diving — and floating tree debris is common enough that small boats always have someone on lookout at the bow to avoid crashing into a partially submerged tree trunk.

These would have been rare voyages, governed by prevailing winds and currents, their success unlikely at best. Serendipity, as well as the generally southward rather than westward currents flowing past the Bird’s Head, accounts for the presence of Death Adders on Obi, Bisa and Seram, but not Halmahera. The timing of the arrival is uncertain, though. This would be a fantastic opportunity to use genomic data to date the population split between the Obi and Bisa snakes and their New Guinean counterparts. No detailed genetic work has been done on the Death Adder — the only scientific paper I could find was concerned with the definition of a new species in northwestern Australia, and it is focused primarily on the phylogenetic analysis of a small number mitochondrial DNA and nuclear loci. A fascinating project for any geneticists prepared to obtain Death Adder tissue samples…🐍🧬

The complexities of Indonesian Fauna, geology and geography are interesting subjects and very much worthy of study👍🏻.

Thanks for shining a light on them