Wallacea

Exploring Indonesia's evolutionary 'Goldilocks Zone'

You can’t travel very far in Indonesia without encountering Alfred Russel Wallace. His presence is felt nearly everywhere, from the pre-trip reading you’ve likely done before arriving here to the displays in the National Museum in Jakarta to the view looking eastward from Bali across the Lombok Strait. Wallace was born in Wales in 1823, and as a self-taught naturalist and professional collector he had already made quite a name for himself in scientific circles before he arrived in Southeast Asia in 1854. His trip to the Amazon with fellow naturalist Henry Walter Bates (of Batesian mimicry fame) from 1848-1852 solidified his reputation, although tragically his collection of specimens was lost when his ship back to England sank in the middle of the Atlantic. After dusting himself off (luckily his sales agent in London had insured the collection for £200, which enabled him to live in London for 18 months) and writing up some of his findings from field notes and the small collection he managed to salvage, he set his sights on what was at that time largely a scientific terra incognita: the Far East.

European colonialists had first reached Southeast Asia in 1511, when the Portuguese seized control of the wealthy Malay trading port of Melaka, and by the early 19th century it was carved up primarily into British, Dutch, and Spanish colonies. Wallace chose to focus on what was then called the Malay Archipelago: the Malayo-Polynesian region encompassing present-day Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and Brunei. It was ruled at the time by Britain and Holland, but very little proper natural history work had ever been conducted in the region. Wallace would soon change that.

He stepped off the boat in the British trading port of Singapore on 18 April, 1854. For the next six months Wallace would collect specimens in Singapore and British Melaka, but his real journey of discovery began in October of that year when he boarded the brig Weraff bound for Sarawak, on the island of Borneo. Invited personally by James Brooke, the first ‘White Rajah’ of Sarawak, Wallace would spend nearly 15 months on Borneo collecting samples and learning about the nature of this fascinating island that’s home to one of the oldest rainforests in the world. While there he would pen the beginnings of a model of biological evolution, published in his famous ‘Sarawak Law’ paper in February 1855.

Wallace returned to Singapore briefly in early 1856, but in May of that year he boarded a ship bound for the island of Lombok in the Lesser Sunda islands of Indonesia, just to the east of Bali. In the map at the top of this post, it’s the island in the far lower left-hand corner, just to the west of Sumbawa — and it’s where Holly and I call home. Wallace would spend 75 days on Lombok, waiting for a boat to take him to Sulawesi and collecting specimens at his first stop in eastern Indonesia. This gave him more than enough time to take in the scenery and begin to formulate yet another deep insight into the evolution and distribution of biological species, which would eventually form the basis of what is known today as biogeography.

It was on Lombok that Wallace began to discover the magic of what would eventually become his namesake, Wallacea. It struck him first in his observations of the avifauna on the island:

Birds were plentiful and very interesting, and I now saw for the first time many Australian forms that are quite absent from the islands westward. Small white cockatoos were abundant, and their loud screams, conspicuous white colour, and pretty yellow crests, rendered them a very important feature in the landscape. This is the most westerly point on the globe where any of the family are to be found. Some small honeysuckers of the genus Ptilotis, and the strange moundmaker (Megapodius gouldii), are also here first met with on the traveller's journey eastward.

Wallace had arrived in a transitional realm between flora and fauna typically found in Asia, which includes all of the islands to the west of Lombok (Bali, Java, Borneo and Sumatra), and the Australasian realm, which includes Australia and New Guinea.

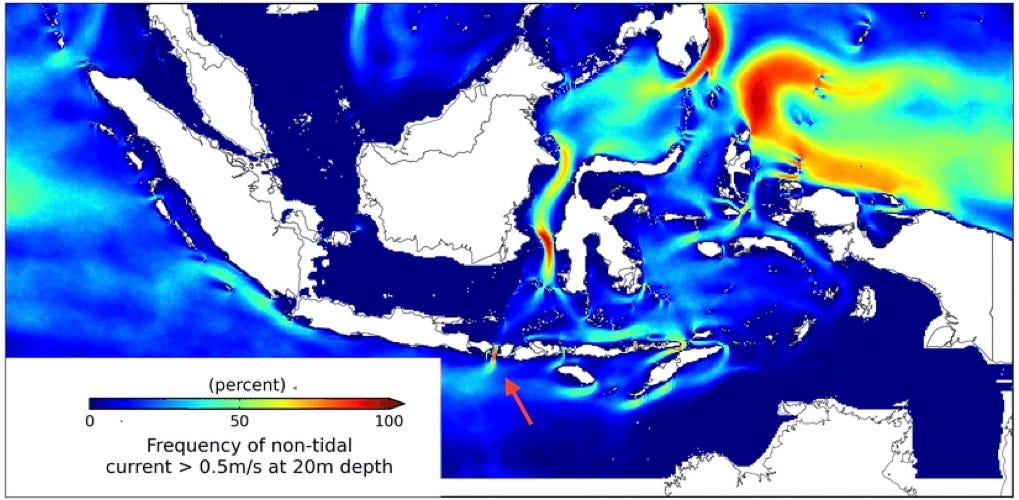

Lombok is separated from the island of Bali by the Lombok Strait, a channel of water between the two islands no more than 40km across at its widest point, and roughly 60km long. What it lacks in surface expanse, though, it more than makes up for in depth. At its deepest, in the region shown in the photograph above, it is ~1400m, and even at its shallowest in the south it is still ~250m. This means that during all of the sea level changes during the Pleistocene, Bali and Lombok were never connected — Lombok is the first island you would have encountered moving eastward from ancient Sundaland. Moreover, although it seems like a simple crossing to make, the currents in the strait are incredibly treacherous — around 20% of the oceanic exchange between the Indian and Pacific Oceans flows through the Lombok Strait, resulting in the drownings of many swimmers over the years. I was once caught in the flow swimming beyond the fringing reef in southeastern Bali, and there is literally no way to fight the strength of the current — if I hadn’t managed to climb onto a cliff face and make my way back into the lagoon on an incoming wave my body probably would have ended up in western Australia a couple of days later.

As you can see in the image above, the western edge of Wallacea is defined by incredibly high levels of oceanic flow — not only through the Lombok Strait, but also in the Makassar Strait separating Borneo and Sulawesi. These deep-water channels have served as natural boundaries to species dispersal for millions of years, largely oblivious to the sea level fluctuations that have characterized much of the region during the Pleistocene. In fact all of the waters in Wallacea are incredibly deep, and the islands have never been joined into a single landmass like Sundaland or Sahul (Australia + New Guinea). The Weber Deep in the Banda Sea reaches a depth of 7,200m, for instance — the deepest point in the world’s oceans not found in a trench — and was formed when a section of the Earth's crust ripped apart by more than 120km, exposing the underlying mantle.

These deep waters, and the extraordinarily high levels of tectonic activity due to the collision and twisting of numerous plates in this part of Indonesia, means that the islands are relatively new. Sulawesi, for instance, only began to coalesce into its current form over the past 15 million years, and only began to assume its current connected form, with a land area nearly as large as Great Britain, in the past few million years. Contrast this with Borneo, which is roughly 400 million years old, helping to account for its ancient rainforest dating to at least 130 million years ago.

What this means is that almost all of the terrestrial species on Sulawesi have been introduced here from elsewhere, relatively recently in evolutionary terms. This provides it with a sort of biogeographical ‘Goldilocks’ status — recent enough that relationships to the source species can still be recognized, but isolated long enough for new species to have evolved, much like the islands of the Galapagos. And evolve they did: 93% of Wallacea’s species of mammal are endemic (excluding bats, which disperse far more easily), and on Sulawesi alone 63% are endemic. It’s no wonder Wallace discovered so many species here during his sojourn in 1856-61, his longest stay in any region of the Malay Archipelago.

The nearby islands of North Maluku, including Ternate, Halmahera and Bacan, have their own fascinating species. The westernmost bird of paradise, for instance — appropriately named Wallace’s standardwing — is found on the islands of Halmahera and Bacan. The world’s largest bee, Megachile pluto (commonly known as Wallace’s giant bee), is found on the same islands. It reaches a length of 38mm, and builds nests in termite mounds. The species was thought to be extinct for over a century until it was rediscovered in 1981 and then again in 2018, when one was offered for sale on eBay.

The high degree of endemism in Wallacea has also created species with enormous commercial value, leading to their nickname: the Spice Islands. Nutmeg, the seed of the fruit of Myristica fragrans trees endemic to the Banda Islands in Central Maluku, is perhaps the most famous (along with the nut’s outer covering, which is known as mace). Enormously valued by the Romans and medieval Europeans for its flavor and supposed medicinal properties, nutmeg made these tiny islands some of the most valuable real estate in the world in the 17th century — famously ceded to the Dutch by the English, who took the island of Manhattan in return, and voilà, New Amsterdam became New York. Similarly, cloves, the flower buds of the Syzygium aromaticum tree, are endemic to Ternate, Tidore and a few nearby islands in North Maluku. They are highly valued for their pungent aroma and numbing properties, and are a key ingredient in Indonesian kreteks (cigarettes). The earliest evidence of long-distance trade in cloves comes from Bronze Age finds in Syria dating to the 2nd millennium BCE, and their trade in China was so well established by the 3rd century BCE that Han emperors required all court visitors to freshen their breath by chewing them (oral hygeine clearly wasn’t that great at the time). The natural monopoly on clove production provided by Wallacea’s endemism made the sultans of Ternate and Tidore incredibly wealthy, although they wasted much of their geographic largesse on waging almost constant war against each other.

Finally, it was on the island of Ternate that Alfred Russel Wallace wrote his famous essay sent to Charles Darwin, supposedly based on an insight that he had while in a malarial fever during a collecting excursion to nearby Halmahera. In this essay he outlined a model for the evolution of species by natural selection, which Darwin himself had been working on independently for many years. When Darwin read Wallace’s essay in June 1858 it spurred him to compose a short description of his own theory of natural selection, urged on by his colleague Charles Lyell. These two papers were read and published together at the Linnean Society in London in the summer of 1858, and the sudden urgency of completing his much more extensive discourse on the topic finally led Darwin to finish On The Origin of Species and publish it the following year. The most important scientific insight of the 19th century — the description of evolution by natural selection — arguably had its genesis, at least in part, on a remote island in Wallacea.