In my previous post I was off on the ferry from Labuan Bajo, on the island of Flores, to Bira in South Sulawesi. The crossing took around 26 hours, not counting a two-hour delay in leaving, and included a 3am stop to unload cargo at the island of Jampea in the Selayar Islands in the middle of the Flores Sea. The activity at a remote eastern Indonesian harbor in the middle of the night is something few casual travelers have an opportunity to witness, but it’s a key part of understanding these far-flung places, which often only have a weekly ferry linking them physically to the outside world, even if they have 4G wireless service these days. It gives you a glimpse of what travel was like in the pre-airline era — not so very long ago in this part of the world.

Probably the best way to experience eastern Indonesia is to travel between islands by boat, in the way people have done since time immemorial — and possibly since the late Pleistocene, based on the archaeological and genetic evidence I discussed in a previous post. Direct flights between smaller destinations are rare, and in this case I needed to get the jeep to Sulawesi to begin the real ‘expedition’ part of my trip through Wallacea.

The crossing went well, with only a bit of nasty weather at the end of the journey, a few hours before we docked at Bira, the main port on the far southeastern coast of Sulawesi’s western peninsula. Nothing major, but some noticeable rolling on the ship and rain falling sideways into the car deck. We finally arrived in Bira around 4pm, and I made my way to the guesthouse I would be staying for a couple of nights.

The weekend brought an onslaught of tourists from Makassar, capital of South Sulawesi and a 6-hour drive away to the northwest, and the activity of choice was being dragged around the bay in front of the beach on a gigantic float, the passengers’ screams mixing with the revving boat engine. At least I had been able to do some meditative snorkeling on the reef before they arrived.

It was time to move on to Makassar, but first I stopped in to see some traditional phinisi making near Bira — the center of traditional shipbuilding in the Indonesian archipelago. Historically the villages would have felled trees in the nearby forests and dragged them down onto the beach where the ship would be painstakingly constructed by hand over the course of 18-24 months. They are still built by hand — and given that, the size of the ships is extraordinary, usually around 30m or so — but these days the lumber is shipped in from other places in Sulawesi or nearby Kalimantan, as the local supplies of the tropical hardwoods used in construction have now been mostly exhausted in South Sulawesi itself.

These ships are the most quintessentially Indonesian style of traditional boat used in the archipelago. Historically used for shipping goods from eastern Indonesia to markets on Java and the Malay Peninsula, they have now largely become synonymous with the tourist liveaboard industry, their shipping role replaced by modern steel-hulled vessels in the 1970s and 80s. Some of the liveaboards are quite luxurious, and it really is a marvelous way to explore the thousands of islands and dive sites of the eastern part of the country if you have the dosh.

![Sulsel linguistic map [Converted] Sulsel linguistic map [Converted]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!b-pW!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F02e85122-3aa5-47f9-a2a7-6876a67a1be6_565x883.jpeg)

The people who build these ships are the undisputed ‘Lords of the Seas’ in Indonesia. Ethnically classified into the Bugis and Makassarese, they are the descendants of the first Austronesians to settle the southern part of Sulawesi in the 2nd millennium BCE. The Makassarese, native to the region around the port city of Makassar, essentially seem to be a mixed population of Buginese and settlers from the Malay Peninsula, so the Bugis are in a sense the ‘aboriginal’ Austronesian population in this part of Sulawesi. On the map of languages in Sulawesi — one of the most diverse regions of the world linguistically — you can see that the Bugis language is unusually widespread compared to the others. Why has it become so dominant?

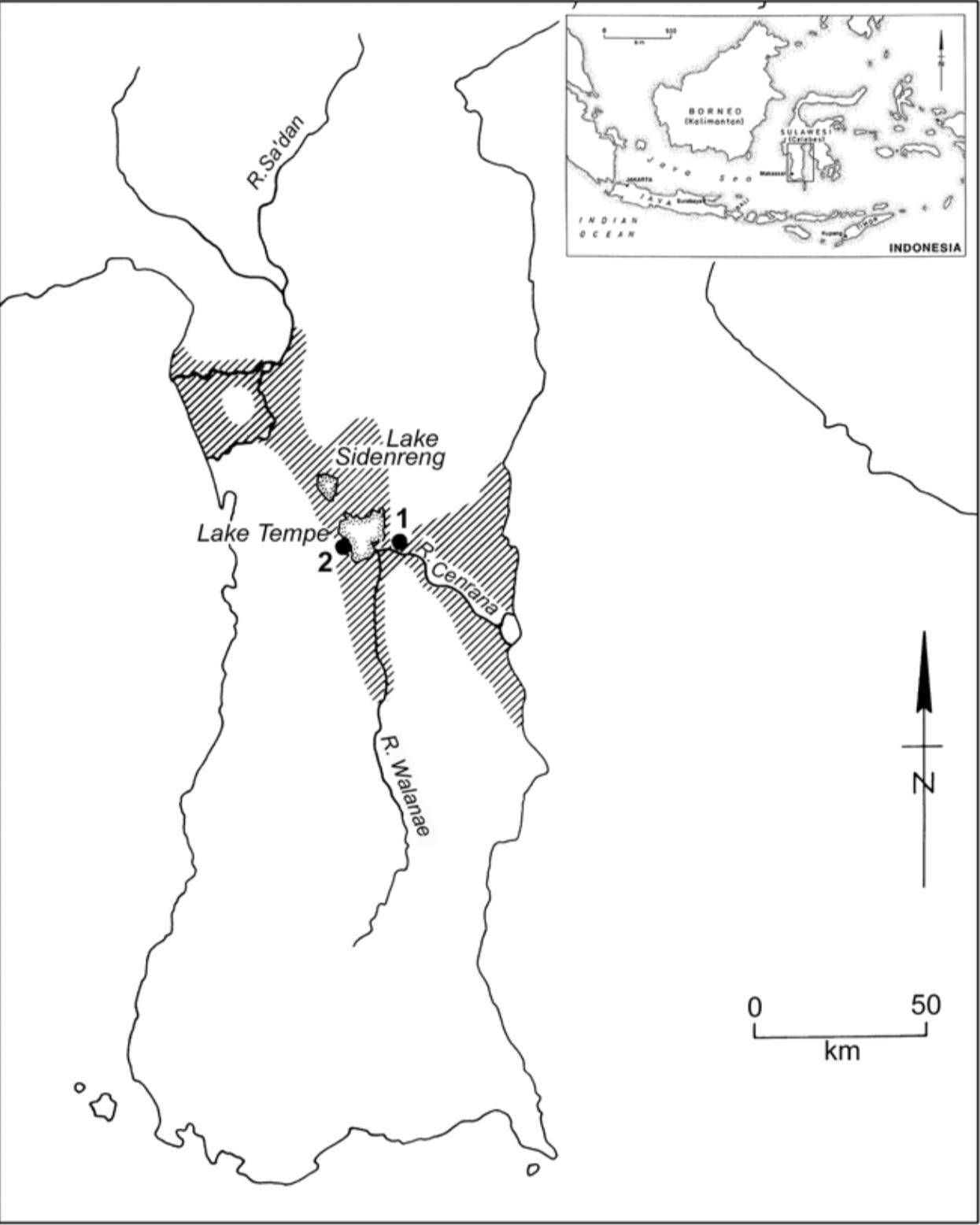

The answer has to do with the unusual topography of South Sulawesi. Today, much of it is lowland rice fields, flat land stretching around the highlands east of Makassar. A few thousand years ago, though, when the Austronesian-speaking ancestors of the Bugis first arrived on the island from the Philippines, likely via Borneo, some of it was actually underwater. This is due to the fluctuations in sea level that occurred during the mid-Holocene, as well as the ongoing uplift of Sulawesi itself. Recall from a previous post that Sulawesi is a very new island, with the majority having risen above the waves due to tectonic activity only in the past few million years. This combination meant that the lowest part of the island today, around Lakes Tempe and Sidenreng, would have been estuarine environments accessible from the Makassar Strait and Gulf of Boni. Even today the great rivers of the region, including Walanae, Cenrana and Sa’dang, can be used to navigate throughout the South Sulawesi interior.

These inland waterways enabled the rise of the Bugis kingdom during the 13th-16th centuries. Even long after the estuarine environment separating South Sulawesi from the rest of the island faded into myth, the rivers allowed the Bugis to crisscross the peninsula in far less time than early European arrivals at the end of this period. Coupled with an intensification of rice agriculture in the rich paddyfields around the central lakes, the human population exploded. The Bugis built the capital of their kingdom not on the coast, but next to Lake Tempe, near present-day Sengkang — the heartland of their rice-fuelled empire.

Much of the rice was exported to China, allowing the Bugis to accumulate great wealth — along with massive quantities of Chinese ceramics, which are ubiquitous in the younger layers of any archaeological site of the region. Most date from the late Ming and Qing dynasties.

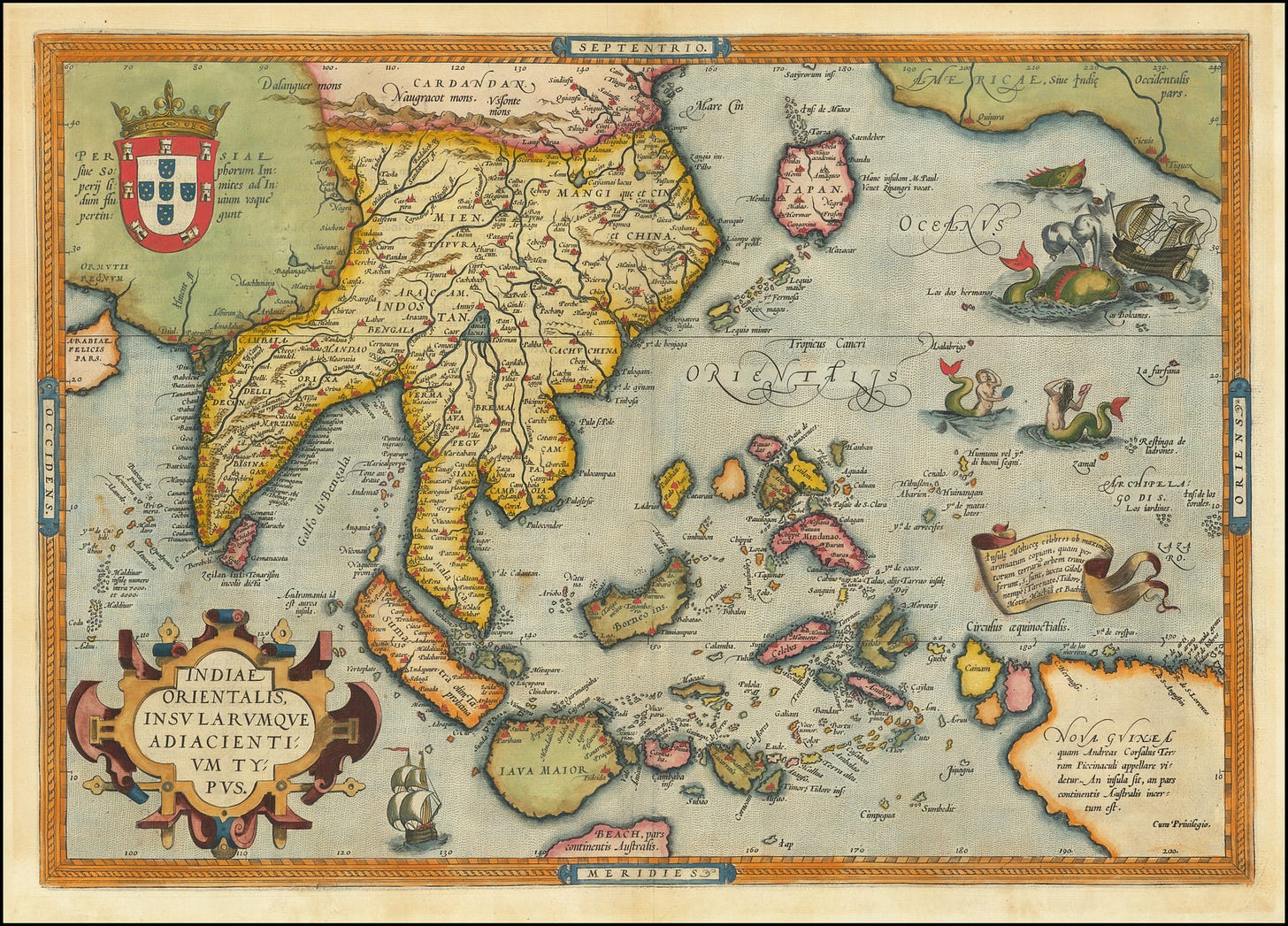

The ability of the Bugis to navigate across the peninsula using inland waterways, coupled with the odd shape of the island, with four long peninsulas and a highland central region, led early European explorers to believe that it was actually an archipelago of separate islands. This makes sense, given the unusual shape produced by its unique setting at the boundaries of several tectonic plates. The Sulawesi coastline, for instance, is 5478km long. Compare this to Borneo, the largest island in Asia (roughly 6x the size of Java) at 4971km. In comparison, Sulawesi’s surface area is only ~186k square km, roughly a quarter the area of Borneo (~743k square km).

Nonetheless, it is Makassar and the region immediately inland from the port city that is most associated with the Bugis. These master seamen dominated trade with eastern Indonesia since the first millennium, and it was the Bugis and their descendants, the Gowa and Tallo kingdoms, that Europeans encountered on their early voyages to the region. As the Portuguese and Dutch gradually established colonies and sought to control maritime trade themselves, the Bugis naturally revolted — often resorting to piracy out of desperation. The European term ‘boogeyman’ may have originated in these encounters, as the Bugis’ exceptional seamanship made them formidable foes.

The final stand of the Gowa kingdom against the European invaders came in battles fought in 1667-1669, when the Duch seized control of the Gowa stronghold of Ujung Padang from the Gowa Sultan Hasanuddin. The ruins of this fort became the foundation of Fort Rotterdam, which still stands near the port area of Makassar. South Sulawesi had finally been incorporated into the rapidly growing Dutch East Indies empire. The precolonial history has lived on in the modern place names in Maksassar, however: from 1971 to 1999 the city was renamed Ujung Padang, and the IATA code for its Sultan Hasanuddin International Airport remains UPG from this period. The main university in the city is also named after Hasanuddin.

Alfred Russel Wallace arrived in Makassar from Lombok on the 2nd of September, 1856, when the Dutch were near the peak of their power in the Malay Archipelago. He wrote:

Macassar was the first Dutch town I had visited, and I found it prettier and cleaner than any I had yet seen in the East. The Dutch have some admirable local regulations. All European houses must be kept well white-washed, and every person must, at four in the afternoon, water the road in front of his house. The streets are kept clear of refuse, and covered drains carry away all impurities into large open sewers, into which the tide is admitted at high-water and allowed to flow out when it has ebbed, carrying all the sewage with it into the sea. The town consists chiefly of one long narrow street along the seaside, devoted to business, and principally occupied by the Dutch and Chinese merchants' offices and warehouses, and the native shops or bazaars. This extends northwards for more than a mile, gradually merging into native houses often of a most miserable description, but made to have a neat appearance by being all built up exactly to the straight line of the street, and being generally backed by fruit trees. This street is usually thronged with a native population of Bugis and Macassar men, who wear cotton trousers about twelve inches long, covering only from the hip to half-way down the thigh, and the universal Malay sarong, of gay checked colours, worn around the waist or across the shoulders in a variety of ways.

Joseph Conrad, during his time as a merchant seaman in the East Indies, also remarked that Makassar was “the prettiest and perhaps, cleanest looking of all the towns in the islands”. Today the fourth-largest metropolitan area in Indonesia, and largest city east of Java (by far), it is indeed a clean and attractive place. I based myself here for my exploration of the Pleistocene cave art in the nearby Maros region, which I’ll cover in my next post.

Absolutely fascinating.

So interesting. And your photos are 🤌🏻🤌🏻🤌🏻