Sulawesi's extraordinary karst galleries

The Maros-Pangkep region is home to the world’s oldest figurative art

Alfred Russel Wallace arrived in Makassar in early September 1856, staying until he set sail for the remote Aru Islands in December of that year to see (and collect) their Australasian fauna. It was on his second visit, in July-November 1857, that he ventured inland beyond the immediate environs of Makassar and its outlying Dutch plantations, into the Maros region. Here, in the rugged karst landscape, he was in search of specimens of the fabled Celebes butterflies, and he collected many examples from throughout the region. “I have rarely enjoyed myself more than during my residence here,” he wrote of his time in the Maros. Australian archaeologist Adam Brumm and his Indonesian colleague Budi Hakim retraced Wallace’s travels in the Maros karsts in the late 2010s — their paper is a fascinating combination of fieldwork and historical research that helps to fill in the gaps in Wallace’s own writings.

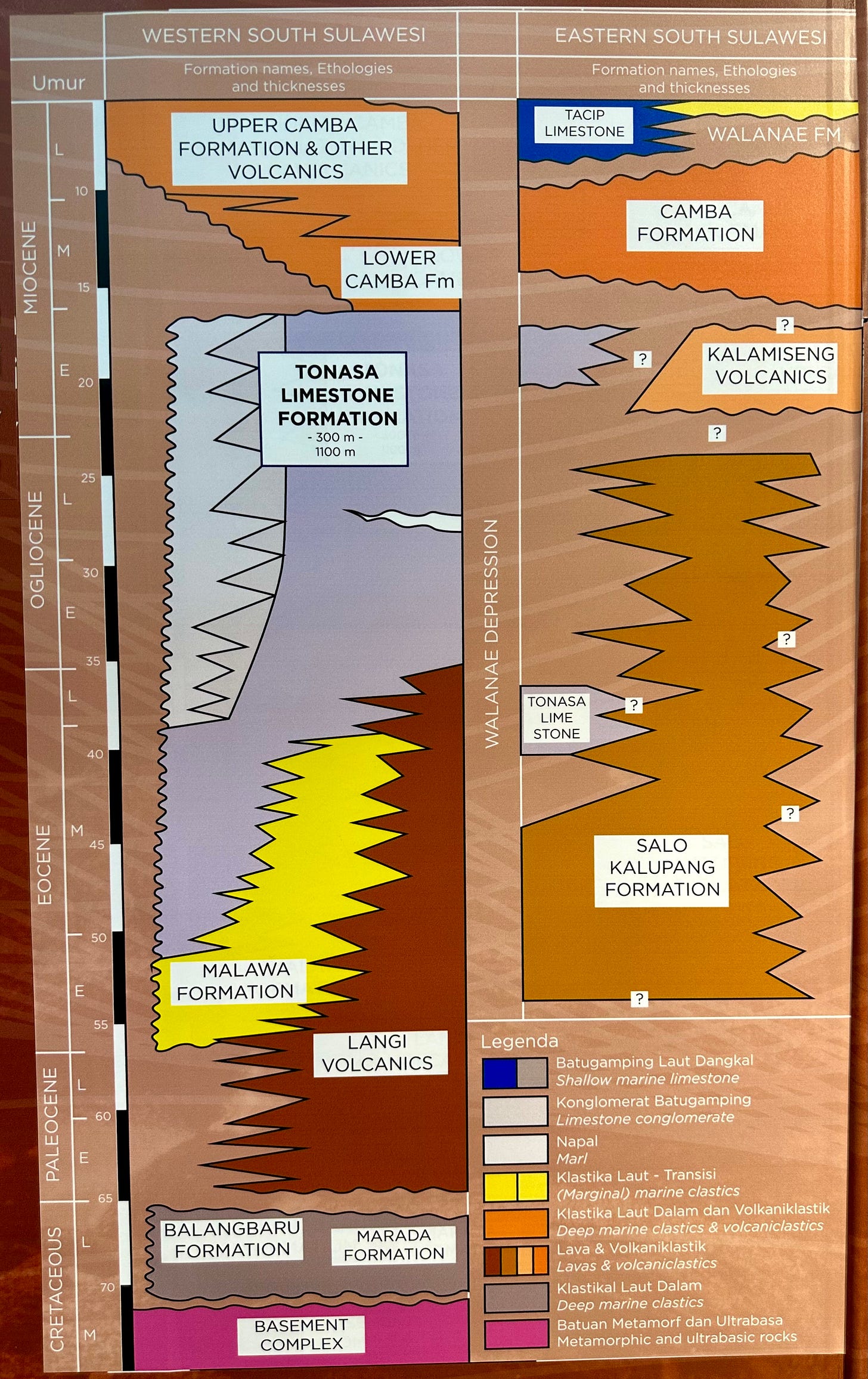

What is karst, though? Craggy cliffs of eroded limestone, in essence. In the case of the Maros region, these originated as shallow coral reefs between 50 million and 15 million years ago when most of Sulawesi was still underwater. Through the gradual tectonic uplift that gave Sulawesi its current form, they were thrust above the waters of the Flores Sea in the past few million years. Recently named a UNESCO Geopark, the Maros truly is a geological wonder, and one of the largest karst formations in the world.

Caves in the eroded limestone cliff faces are easy to spot anywhere in the Maros, and the local Buginese people have used them for shelter and events throughout recorded history — one of the most famous caves, Leang Panninge, even serves as the venue for local badminton tournaments. Given how common they are, it’s perhaps surprising that the art on the cave walls wasn’t discovered until 1950. Dutch archaeologist Hendrik van Heekeren was leading an excavation at Leang Pettae cave, accompanied by a young graduate student named Clementine Henriette Marie Heeran-Palm, when she wandered into a deeper part of the cave:

On February 26th, when the first sector was being excavated, Mrs. C.H.M. Heeren-Palm was inspecting the interior of the cave when suddenly she discovered, at the end of the cave on the ceiling, several negative hand-stencils on a red background. In total 7 hand-stencils were spotted. Against one of these a crescent-like shape in red was observed, a little further a figure with five oblong stains, perhaps representing another hand-stencil. It became evident that in prehistoric days left hands had been spread with the palm against the ceiling and a red pigment splashed or spat all around them. Splashes of red paint on nearly all hands proved that the stencils were made one after another. In many places the red pigment had blistered so badly that many details were lost. All were stencils of left hands, with slender fingers probably belonging to women. Next day I found in the same tunnel, a little further inwards and on a lower part, a fine contour drawing in red striped-line technique of a charging boar with 5 or 6 tufts of hair on its neck and back. On the head were 2 horn-like objects. D. A. Hooijer, palaeontologist and zoologist, to whom I sent a reproduction, observed that the horns were bent with the crooked part forwards instead of backwards. As a matter of fact they were portrayed in the same way as the tufts on the back and neck. This is all the more remarkable as Babyrousa, of which the slender legs and clumsy body remind us, has no hair at all. In the cardiac region an object was pictured, evidently a spear-head. Is it possible that we are here dealing with a symbol of sympathetic magic, expressing the wish to strike the game in its most vulnerable spot.

Finding ancient cave art, especially in a location like Sulawesi where none had previously been described, immediately raised the question of how old it was. In the absence of reliable dating methods for the ochre pigment used to create the Maros paintings, mid-20th century archaeologists deferred to their own biases: it likely dated to the time after the arrival of the Austronesians on Sulawesi in the second or third millennium BCE. Thus, it was old and clearly interesting, but not Earth-shatteringly so — just another example of how the Austronesians introduced modern human culture to island Southeast Asia. Even today, tourist guides at the most frequently visited cave art site in the Maros, Leang-Leang (which includes Leang Pettae), often tell visitors that the art dates to the Holocene — a few thousand years old.

This all changed in the early 21st century. Uranium-series dating methods were originally developed in the 1980s, and they have revolutionized the study of ancient cave art. By dating the speleotherm ‘popcorn’ deposits of calcium carbonate precipitated on the surface of a painting or petroglyph, archaeologists have a tool for assessing the minimum age of previously undatable art. When this was applied to the Maros paintings in the 2010s, the results made headlines around the world.

Up until this time the famous figurative cave art of southern Europe — Chauvet, Peche Merle, Lascaux and Altamira, among others — was thought to be the oldest in the world. The amazing creations at Chauvet date to around 37,000 years ago, for instance — originally thought to be the harbinger of the arrival of behaviorally modern Homo sapiens in this part of Europe. While these are very old dates indeed, the Maros artwork pushed the envelope even further into the past.

The Leang Bulu Sipong 4 cave contains beautiful paintings of anoas, a species of dwarf buffalo endemic to Sulawesi, as well as wild pigs and half-human creatures known as therianthropes. When these were dated using Uranium-series techniques in 2019 they were revealed to be 43,900 years old — the oldest figurative cave art ever discovered at the time. The therianthropes hint at a quasi-regious conceptualization of a world beyond the mundane, and are a fascinating insight into the culture of the people who created them.

The Leang Tedongnge cave has since yielded even older figurative art, dating to 45,500 years ago. Sequestered away in a ‘hidden valley’ in the Maros karst, this cave is only accessible by a strenuous 2.5-hour climb over loose, sharp karst fragments up through the jungle, over the top of the karst formation and then down into a fertile valley inhabited by a few local rice farmers. In the wet season the fields are submerged in a meter or more of water, so access is limited to the dry months. Its remoteness assures security, which was an issue until one of the local farmers was hired to serve as a caretaker. We camped on the front porch of his stilted house when we visited, washing with and drinking the water (boiled) from the tiny village’s communal well. Needless to say, the visit was an unforgettable experience.

Two things are striking about the ancient cave art in the Maros. First, that it has only been discovered very recently. Leang Tedongnge was only discovered in 2019, for instance, as part of an intensive survey of potential cave art sites in the Maros carried out by Budi Hakim, Basran Burhan and their team from the archaeology research center in Makassar. This suggests that there is far more still waiting to be discovered. The second striking aspect of the Maros cave art is how old all of it is — most of it dates to the Pleistocene, over 25kya. It seems to have suddenly appeared fully-formed in this part of Sulawesi between 45-50kya — there are no antecedents with more primitive features yet discovered. While we can’t rule this out, of course, it does suggest that it arrived from somewhere else, perhaps as part of the initial migration of fully modern humans to Sulawesi.

The most likely source of this migration is from Borneo across the Makassar Strait, where similarly old cave art has been discovered in East Kalimantan. Was there a rapid expansion of culturally advanced humans through island Southeast Asia around 50kya, perhaps leading to Australia? I’ve discussed the evidence of a modern human presence in Southeast Asia from perhaps ~80kya in a previous post, though it’s possible that these early settlers were replaced by a later wave of behaviorally modern humans. The jury is still out, though, and as I said in that post, one of the ‘Holy Grails’ of Southeast Asian prehistory is to characterize genetically just who the first modern humans in Southeast Asia were — ideally from Pleistocene human remains associated with the ancient cave paintings in Sulawesi or Borneo.

The extraordinary cave art of the Maros has been preserved for nearly 50,000 years — a huge expanse of time. It is rather poignant that the environment that has assured its preservation is within caves made from the skeletons of dead animals — the former coral reefs that form the karst — which have maintained ideal conditions of humidity and temperature for tens of thousands of years. This natural material is now threatened, however, because of its valuable chemical composition. Cement companies have been granted long-term leases to mine the karst, which they are pursuing with ruthless efficiency. Bulu Sipong is actually located on a cement company’s land, and to visit you need both government approval and written approval from the company. While the cement company employees I met on my visit to the cave seemed committed to the long-term preservation of the priceless art in their care, one does wonder what the eventual limits to this caretaker relationship might be. The combined forces of shareholder value and local economic development in a poor region are powerful foes to long-term preservation.

Even if the cement companies are up to the task, though, climate change is creeping inexorably into the equation. Changes in rainfall patterns are leading to exfoliation of the caves, as mineral-rich sediments seep into the interiors and dislodge chunks of limestone from the painted surfaces. The art in its current state of preservation may only be recognizable for a few more decades. I feel incredibly lucky to have been able to have seen it now — in all likelihood it won’t survive for future generations to have the same opportunity.

A reminder of the long-term ebb and flow of cultural influences in South Sulawesi can be found today in traditional Buginese houses. As these houses are being constructed, the families building them carry out a ceremony known as the Mabedda Bola. In this ceremony, family members place their handprints on the support pillars of the house to signify ownership and to ward off evil influences. While it’s unknown what the function of the hand stencils were in Pleistocene caves, they are likely to have played a similar role. Long-term interactions have been well documented between the Toaleans — the pre-Austronesian inhabitants of Sulawesi who were, at least in part, the descendants of the Maros cave artists — and the Buginese after their arrival on the island, allowing for extensive cultural exchange. Perhaps the Buginese handprints are a remnant of these interactions — a poigant, living fragment of the extraordinary figurative art created in the region tens of thousands of years ago.

Excellent and informative article. I visited the most well-known cave about 10 years ago and the staff archeologists were extremely helpful and happy to help. Even just the "easy" hand print was difficult for me, cliimb up a few large boulders and twist your head in a very uncomfortable position. But very memorable and exciting. By the way right around the corner are huge active marble quarries.