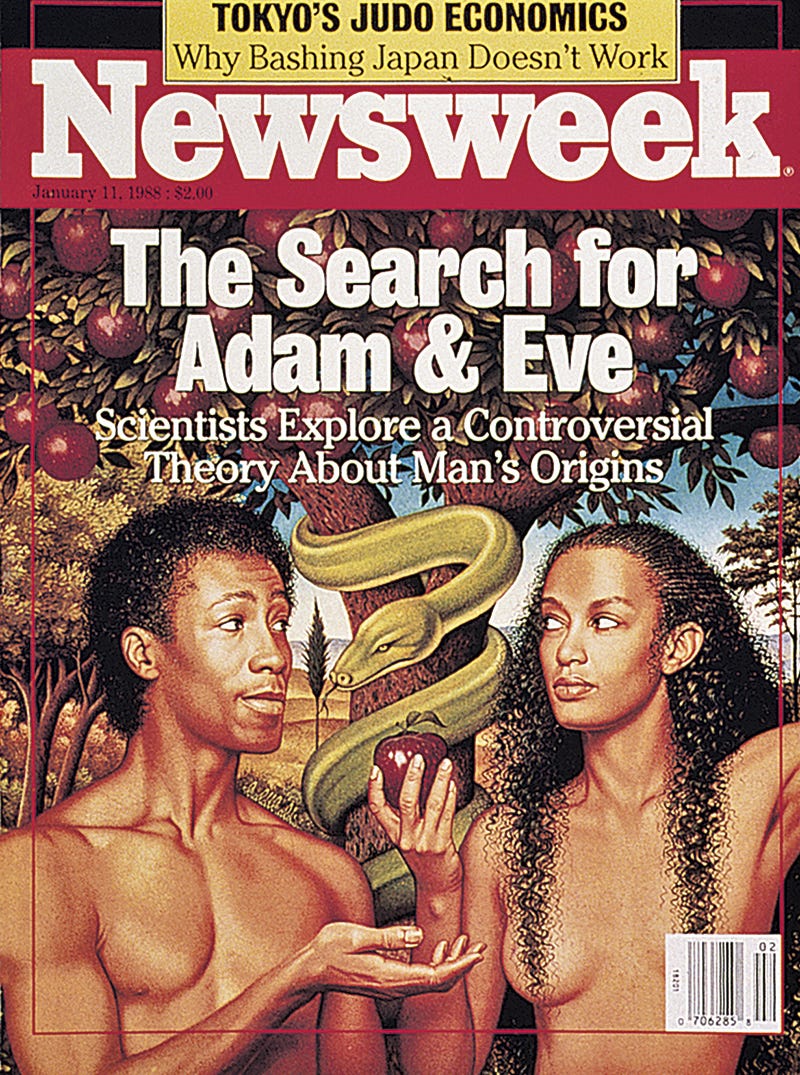

My career as a scientist has been marked by two significant paradigm shifts in the study of human origins. I started my PhD in 1989, two years after Rebecca Cann, Mark Stoneking and Allan Wilson published their groundbreaking paper on mitochondrial DNA showing that all humans around the world share a recent common female ancestor around 200,000 years ago (200kya) in Africa. By 1988 ‘Mitochondrial Eve’, as she was dubbed, had gone mainstream — she even made the cover of Newsweek, a popular American weekly news magazine. It seems such a bedrock scientific finding now that it’s easy to overlook how revolutionary — even controversial — it was at the time.

Why was it so controversial? Many reasons, ranging from technical concerns about the analysis to overt racism. While many had argued for an African origin of humans for decades — since at least the time of the discovery of Australopithecines in southern Africa in the 1920s — many scientists in the 1980s thought that the primary migration of human ancestors out of Africa had occurred during the time of Homo erectus perhaps a million or more years ago, and that human ‘races’ had evolved into modern humans separately in different parts of the world. This so-called ‘multiregional’ model of human origins had many adherents in the paleoanthropological community, which had dominated the study of human origins for over a century, and the notion that modern humans had emerged fully-formed from an African homeland much more recently was a shock. The fact that this challenge to the orthodoxy came from a genetics lab rather than the study of ‘stones and bones’ was also a difficult pill for many in the field to swallow. Finally, many nonspecialists simply refused to believe that their recent ancestors had come from sub-Saharan Africa: surely Europeans and East Asians were so different from the people of this region that they must have been evolving separately for much longer!

While there were some early and valid technical concerns about placement of the root of the mitochondrial tree, an African root was later shown to be correct when more genetic data was available in the early 1990s.1 By the time I began my postdoctoral work in Luca Cavalli-Sforza’s lab in 1994 it was pretty much the mainstream scientific view. One significant question remained, though: if all modern humans ultimately had a recent common African ancestor, when did they first emerge from this continent to populate the rest of the world?

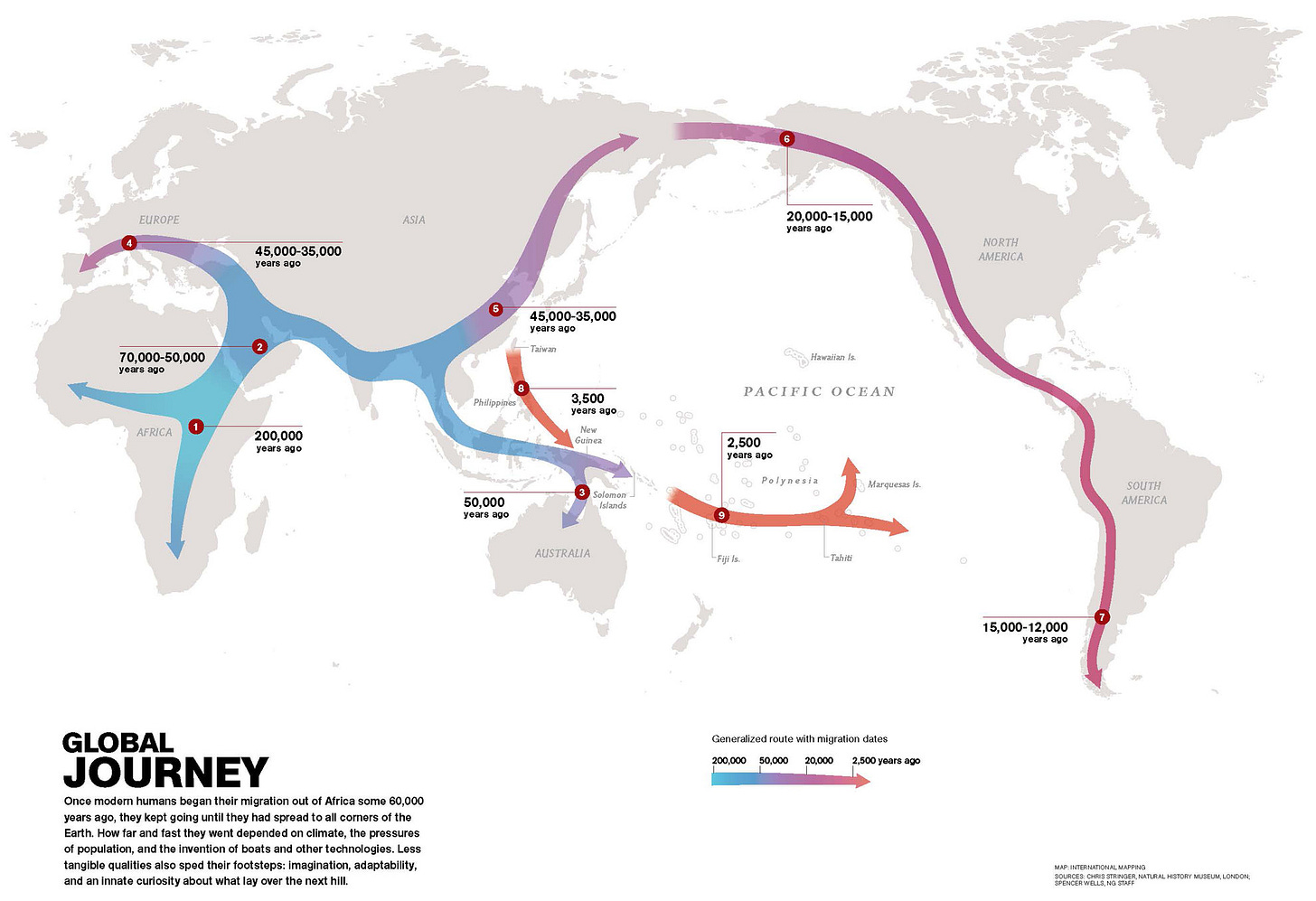

The answer to this would have to wait until more was known about the non-African patterns of diversity of both mitochondrial DNA and the Y-chromosome, along with accurate estimates of the ages of the lineages. The consensus that emerged by the beginning of the 2000’s was that humans had emerged from Africa very recently - around 50-60kya, or ~2,000 human generations. My book The Journey of Man traced these early journeys around the world using Y-chromosome data. More recent studies of data from across the entire genome have confirmed these estimates, firmly placing the date of the African exodus at ~60kya. Consistent with this, modern human fossil remains in Europe, the Middle East, Central/South Asia and the Americas all date to after this time.

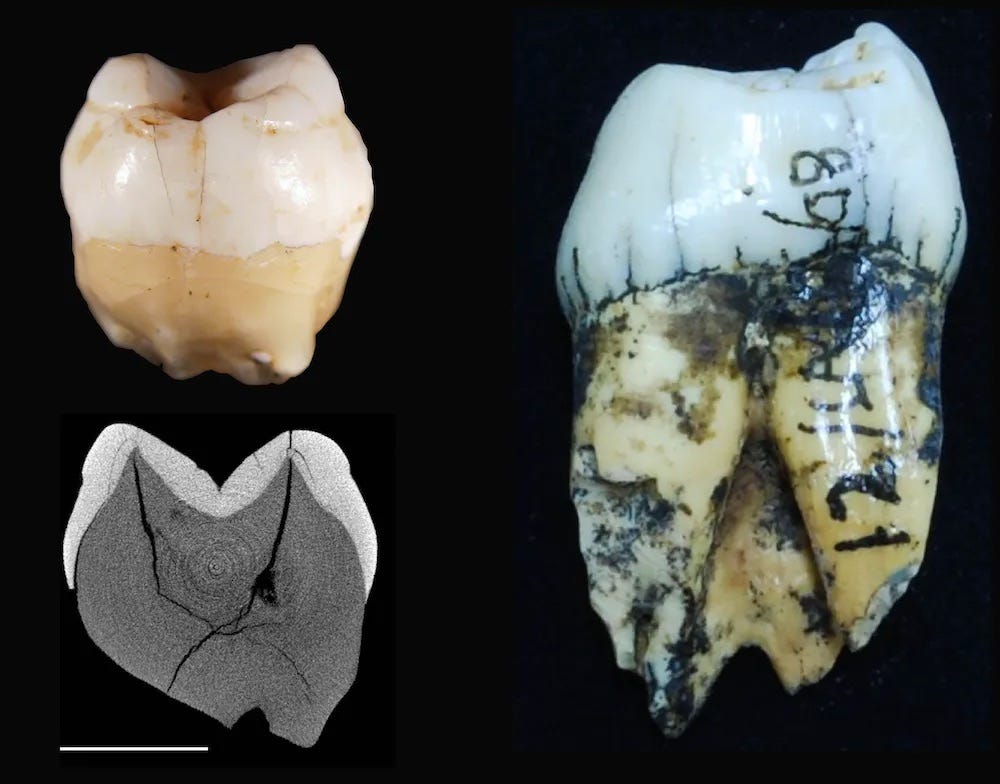

Unfortunately a wrench is thrown into this simple model when we arrive in Southeast Asia. In much the same way that Homo erectus in the region seems to date to ~1.8 million years ago, at roughly the same time as their earliest exodus from Africa, modern humans are also found in the region far sooner than they would be expected to have arrived here. The earliest evidence discovered thus far comes from two sites: skull fragments excavated at Tam Pà Ling cave in Northern Laos, and two teeth found at Lida Ajer cave in western Sumatra. The Laotian remains have been dated to between 63kya and 46kya, while the Sumatran teeth date to between 73kya and 63kya. A new find in the deeper layers at Tam Pà Ling dates to as much as 86kya, though this hasn’t been peer reviewed yet. Finally, human remains and microlithic stone tools found in Traders Cave in the Niah Caves complex in Sarawak, Malaysia, apparently date to >60kya, though this is currently unpublished.

Taken as a whole, the weight of evidence clearly indicates a human presence in Southeast Asia prior to 60kya. While any particular find can be dissected and issues can be raised about the excavation or dating methods (e.g. Lida Ajer), the consistent regional pattern simply cannot be easily dismissed on the basis of archaeological nitpicking. Part of the reason that this pattern is particularly striking in Southeast Asia is because of how little paleoanthropological work has been done in the region at all, compared to, say, Africa and western Eurasia. Until recently there has been a notable dearth of Late Pleistocene human fossils from Southeast Asia compared to elsewhere, so this makes it even more surprising when the ones that have been found are consistently quite old.

Where does this leave us with the genetic dates, which are quite clear about an African exodus at 60kya? There are two options. First, the genetic dates may be incorrect. Not completely, of course — they are clearly in the right ballpark, as no modern humans have been found in Asia or elsewhere outside of Africa and the Middle East that date to ~100kya — but perhaps off by ~20,000 years. This seems unlikely given the relatively robust methods of whole-genome genetic dating used, but it is a possibility. The second option is that these pre-60kya remains from Southeast Asia are like the early humans found in the Middle East — Homo sapiens that left Africa prior to 100kya in small numbers, some of which found their way to Asia, but were later completely replaced by modern humans within the past 60,000 years, perhaps aided by the Toba supereruption. This would certainly be consistent with the genetic data, but many researchers feel that Toba’s impact has been greatly overstated, with signs of continuity in stone tools across the eruption boundary in India, for instance, despite significant ash deposits there. What would solve this thorny issue in the peopling of Southeast Asia is ancient DNA obtained from the excavated remains.

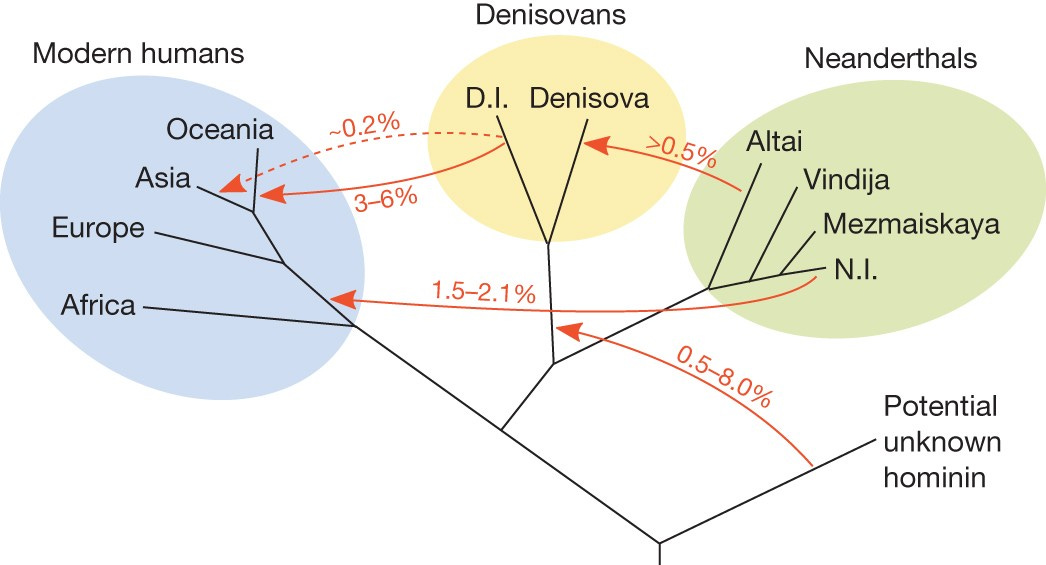

If the Late Pletistocene human remains discovered so far in Southeast Asia are bones with no genetic context, the final denizen of the region’s ‘Star Wars cantina’ that I explored in the second post in this series makes its presence known from DNA evidence alone, with no associated bones yet discovered here: the Denisovans. Denisovans were the first hominins described entirely from DNA, in fact. In 2008, Russian archaeologists working in Denisova Cave in southern Siberia discovered the finger bone of a juvenile hominin that was initially dated to between 50kya-30kya. It was only in 2010, though, when the genome was sequenced by Svante Pääbo’s team in Leipzig that its significance became known: the bone belonged to a new type of human distantly related to the Neanderthals. The DNA showed that the individual from the Denisova Cave shared a common ancestor with Neanderthals ~400kya, and both are effectively distant ‘cousins’ of modern humans, sharing an ancestor with us ~600kya. In the absence of any diagnostic skeletal material, the researchers dubbed her (they could tell her sex from the DNA) a ‘Denisovan’ after the cave. Her discovery threw a wrench into our understanding of human prehistory.

First, there was the fact that this was a creature that had never been seen before in the fossil record — weird by itself, especially as more individuals were discovered in the cave. Since then other ‘ghosts’ have been discovered in genetic data from various populations around the world. Second, there was the fact that some modern human populations carry a significant fraction of Denisovan DNA — but these were all limited to Southeast Asia and Oceania, far from where the Denisovans had been discovered. The closest indigenous populations to Denisova Cave geographically — Kazakhs, Altaians, Mongolians, Chinese — have only the tiniest traces Denisovan ancestry. On the other hand Papua New Guineans, Australian Aborigines and ‘Negrito’ groups from the Philippines such as the Aeta carry as much as ~5% Denisovan DNA — even though no Denisovan remains have ever been found in the area. Bizarre.

It may come as a surprise that modern humans are carrying DNA from our extinct hominin cousins at all, given that for decades they were thought to be separate species. It certainly surprised me (and many others) when it was first announced. The discovery of widespread trysts between human ‘species’ during the Pleistocene is the other significant paradigm shift that has occurred during my career. When the first Neanderthal genome was sequenced in 2010, again by Svante Pääbo’s2 group, it revealed the shocking discovery that a small percentage of of the genomes of modern non-Africans came from interbreeding with Neanderthals (who only lived in Eurasia) during the early exodus from Africa ~50-60kya. The Neanderthal genetic contribution has now been refined to ~2%, and is roughly the same in all non-African populations — Europeans, South and East Asians, Native Americans and Oceanians. The value of ~5% Denisovan ancestry in Negrito and Oceanian populations, on top of their ~2% Neanderthal ancestry, is extraordinarily high and makes the lack of Denisovan fossils in the region even more curious.

A more complete exploration of this Southeast Asian ‘Denisovan conundrum’ will have to wait for a future post. For now, though, who were the first modern humans to migrate to Southeast Asia? Here again, genetics provides some clues — but tantalizingly few at this point, unfortunately. The DNA from present-day populations in the region reveals two primary components. One has been linked to the spread of rice agriculture during the Neolithic period, between ~8kya and ~3kya. This ultimately traces its source back to China, where the East Asian variety of rice (japonica) was first domesticated. As these farmers moved southward from their Chinese homeland, planting rice ever further afield, they intermixed with an earlier population of hunter-gatherers who are thought to have constituted the original settlers of the region in the Pleistocene ~60kya. This earlier genetic component is found at highest frequencies in the remaining hunter-gatherer populations of the region today, like the Aeta of the Philippines and the Orang Asli of Malaysia. This so-called ‘Two Layer’ settlement model was first proposed a century ago in the absence of any modern genetic data, and is still the one that most researchers refer to when discussing the early prehistory of Southeast Asia.

As we have seen from work other regions of the world, though, there have been many migrations throughout human history, and these often have a significant impact on the genetic composition of the populations living there. Third-millennium BCE Bronze Age migrations into Britain, for instance, resulted in a 90% genetic replacement of the Neolithic population that was living there before their arrival (Bronze Age migrations from southern China also had a minor genetic impact on parts of Southeast Asia). The only way to disentangle the tempo and mode of long-term population history in a region is to sample ancient DNA from multiple points in time in order to disentangle the complex historical processes that created today’s genetic patterns. The analysis of DNA from modern human remains dating to ~40kya discovered at Tianyuan in China, for instance, reveals that the oldest genetic component seen in Southeast Asian populations is quite different from the early inhabitants of China. Were 40-60kya Southeast Asians also genetically distinct from the hunter-gatherers found in the region 8,000 years ago — or those living in the region today?

Unfortunately this is where Southeast Asia’s geography — in particular its wet, tropical climate — prevents us from performing the sorts of genetic analyses on samples tens of thousands of years old that have become relatively straightforward in northern Eurasia. DNA degrades rapidly in wet, tropical conditions. No ancient DNA has yet been obtained from Southeast Asian human remains older than 10kya, leaving the analyses of Plestocene population movements to be inferred weakly from these much more recent samples. While the Holocene hunter-gatherers that have been studied so far, dating to between 3kya-8kya, may in fact represent a direct genetic line back to the earliest settlers of the region some 50-60,000 years before, we simply don’t know for sure. The eventual analysis of Southeast Asian Pleistocene DNA will be an enormous leap forward in our attempts to understand the complexity of early human history in the region.

I will be posting on what has been discovered from the oldest complete Southeast Asian ancient genome yet analyzed in a couple of weeks, as I shift focus to an upcoming journey that I’ll be covering in this blog. Up next, though, I will explore the curious geography of the fascinating place where this ancient genome was found: Wallacea.

Brief aside: The radical and seemingly simplistic focus on mitochondrial DNA by Wilson’s group at Berkeley was a large part of the reason I decided not to apply to pursue a PhD there; at the time (1988) this approach was considered to be neither ‘true’ population genetics nor ‘true’ anthropology. I went to work with population geneticist Richard Lewontin at Harvard instead, but I’ve sometimes wondered how my career might have turned out differently had I done my doctoral work with Wilson. One of the true greats in the study of human evolution (his work on the biochemical timing of the human-chimp split in the 1960s-70s was similarly radical at the time), Wilson died prematurely of leukemia at the age of 56 in 1991.

The primary reason Pääbo won the Nobel Prize in 2022.