Southeast Asia: 1.8 million years of human prehistory (Part 2)

Star Wars cantina in the Malay Archipelago

In Part 1 of this series, I talked about the geographical context for humanity’s long-term presence in Southeast Asia. One surprising aspect for many is the existence of vast tracts of savanna nestled in between the present islands of Sumatra, Java and Borneo during much of the Pleistocene, from ~2.5 million to ~12,000 years ago. There is a wealth of evidence for this, dating back to the first settlement of the region by Homo erectus at sites such as Mojokerto. Today’s shallow Java Sea was dry land, and much of it was grassland with a variety of large mammals, including elephants, rhinos, buffalo, tigers, leopards — in short, a place very much like the African savannas the ancestors of Java Man had left just a short time before.

Perhaps the most fascinating thing about this era before the arrival of modern humans around 60,000-80,000 years ago (kya) is that Homo erectus weren’t the only hominin species living here. By 100kya, there were at least four other human species dotted around the islands of the archipelago, each adapted in its own way to the environments of the region. Beyond this, the region was home to a variety of hominoid species — a broader term that includes all of the great ape cousins on the human lineage. Who were these creatures cohabiting in a place that would have seemed like a prehistoric version of the Star Wars cantina, full of distantly-related but quite distinct ape-like species?

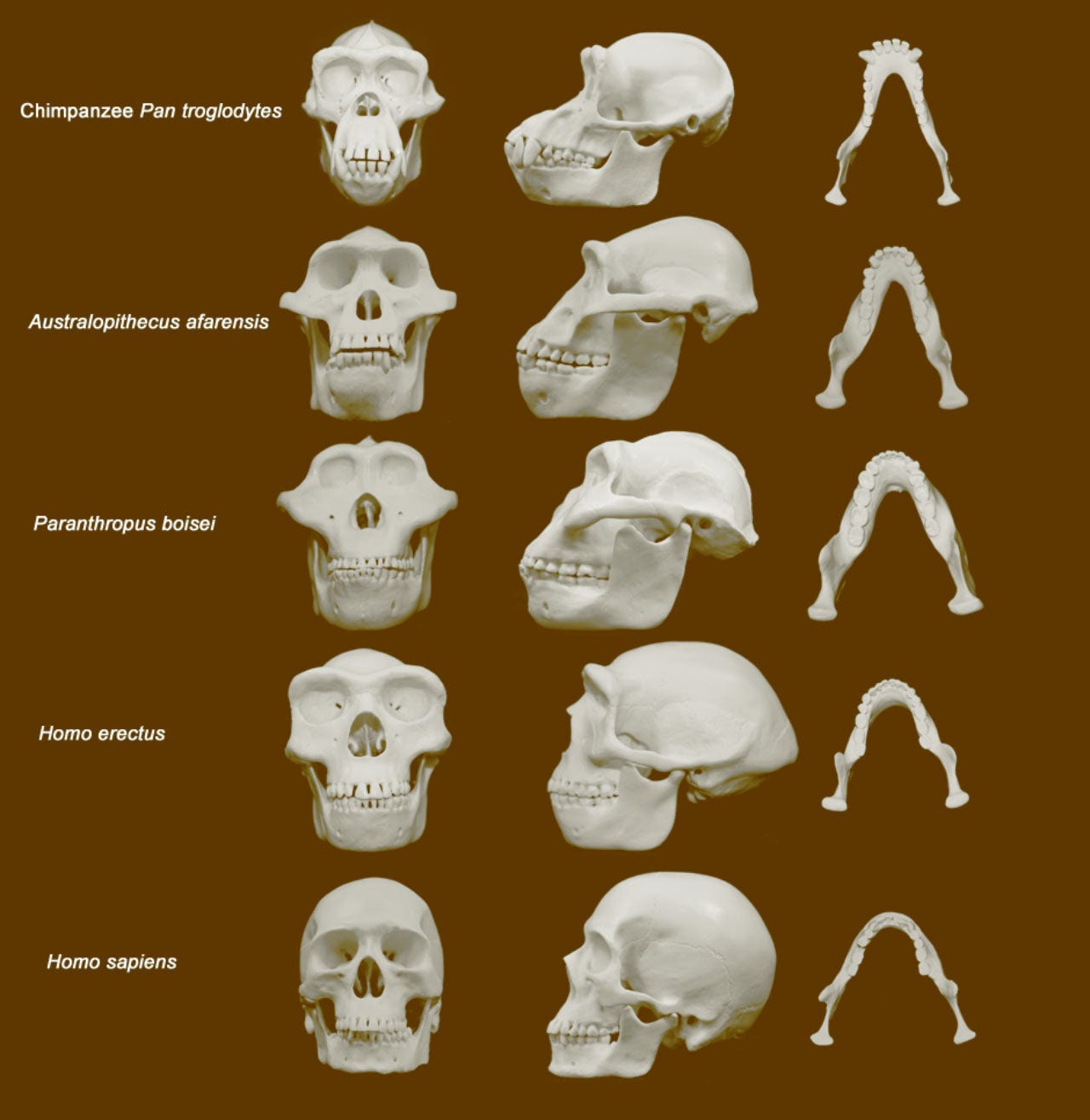

First, let’s get our terminology straight — then return briefly to geology. Hominins include the species most closely related to modern humans, including Homo erectus, but also chimpanzees. Hominines add gorillas to these extant species. Hominids include all of the great apes, with orangutans joining the party. Finally, hominoids add the lesser apes - in terms of present-day species this includes the gibbons, which are found only in Southeast Asia. Collectively, all are classified as apes.

Apes are first found in the fossil record in Africa, with a creature known as Proconsul. Dating to ~23 million years ago, Proconsul lived in Kenya at a time when Africa was completely disconnected from the rest of the world’s landmasses due to the vagaries of plate tectonics. Between 18-20 million years ago Africa bumped into southwestern Eurasia, allowing biological exchange between the two continents for the first time since the breakup of Pangaea nearly 200 million years before. Some of the apes that exited Africa at that time would eventually evolve into the gibbons and orangutans in Southeast Asia. Today, there are three recognized species of orangs — two on the island of Sumatra and one in Borneo. Gibbons have been classified into four genera and 20 species, ranging from eastern India and Bangladesh through Yunnan Province in southern China, down to Java and Borneo. But these are just the ape species surviving today — dig into the region’s fossil record and some really wild things pop up.

Perhaps no extinct ape excites the imagination as much as Gigantopithecus — a real-life King Kong that lived in Southeast Asia between 2 million and ~350kya. The largest ape ever identified in the fossil record, males are estimated to have weighed as much as 200-300kg, and to stand perhaps 2.7m high — at least 25% larger than a mature male gorilla. Unfortunately, no postcranial skeletal material of Gigantopithecus has been found - these estimates are based on gigantic molars and jaws and their similarity to orangutan teeth. Its hard to argue with the massive size estimates, given the 6mm-thick dental enamel and huge tooth sizes. Their validity received a boost in 2019 with the sequencing of proteins from teeth found in southern China, showing that Gigantopithecus was definitely related to present-day orangutans, and confirming that massive orangutan body proportions are likely to be a good proxy for these enigmatic extinct apes.

Humans arrive

In the last post in this series I discussed the arrival of Homo erectus in Java around 1.8 million years ago. This marks the earliest hominin presence in the region, almost immediately after their exodus from Africa, and dating to roughly the same time as the Dmanisi erectus remains in Georgia. These early humans would have encountered Gigantopithecus during their journey through Southeast Asia, and likely cohabited with them on Java. Imagine seeing one of these gigantic creatures — likely completely herbivorous and harmless if left alone, but formidable if threatened. While there is no evidence of direct clashes between them, such encounters must have occurred on occasion. Truly frightening.

Homo erectus lived here until at least 100kya, based on the age of the youngest remains found on Java. Because fossil finds are sporadic, and any particular site will never be the actual first or last of anything, but only a sample from within the date range, it seems reasonable to assume that erectus might have overlapped with the arrival of modern humans in the region between 60-80kya. But even if there was no overlap between them, Homo erectus weren’t alone in island Southeast Asia during their nearly two-million year-long sojourn in the region.

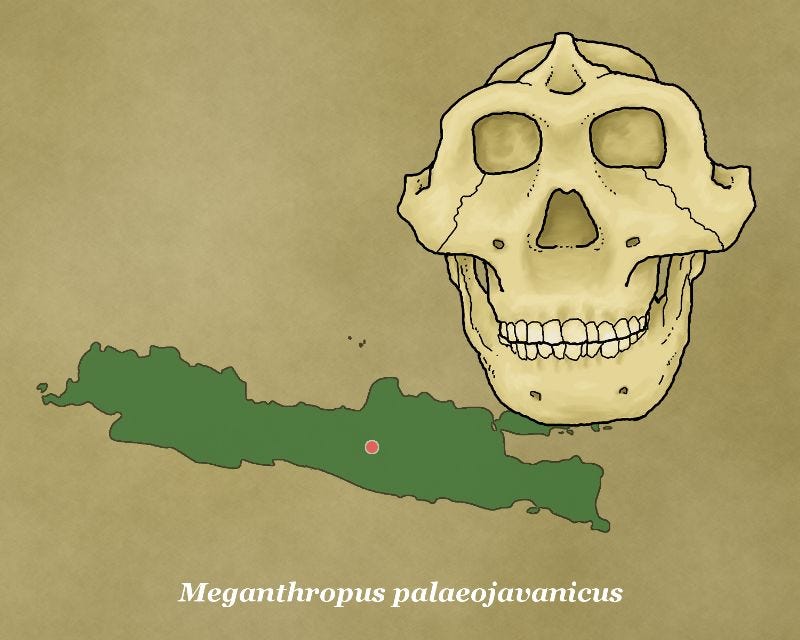

Their island-mates in Java were among the oddest in the hominin menagerie. A jaw was discovered at Sangiran in central Java in 1941 by Ralph von Koenigswald, but when the Japanese invaded in early 1942 he sent a cast of it to the eminent paleoanthropologist Franz Weidenreich at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. While von Koenigswald was interned in a Japanese camp during the war, Weidenreich carefully described and named the specimen, dubbing it Meganthropus palaeojavanicus. It was the largest hominin jaw ever found at the time, and Weidenreich inferred that it belonged to a gigantic human ancestor that was nearly the size of Gigantopithecus - perhaps standing 2.4m tall.

The features of the jawbone are more similar to humans than to apes like orangs, and in many ways similar to the robust Paranthropus boisei first discovered in South Africa in 1938, later nicknamed ‘Nutcracker Man’ for his massive jaws. The Meganthropus teeth were more human than ape-like, and most paleoanthropologists have tentatively assigned it to a particularly robust Homo erectus subspecies that evolved in Southeast Asia. A recent analysis of dental wear calls this into question however, assigning Meganthropus to a non-hominin, non-orangutan ape lineage, despite the overall jaw and tooth similarities to hominins. The jury is still out, then, on exactly what Meganthropus was — hopefully additional skeletal material will be discovered in the future that will help to resolve on exactly where this large-jawed giant sits in the human family tree.

Lest you think that every hominid arriving in island Southeast Asia evolved to become gigantic, however, fossils discovered at two sites ~3,000km apart in the past 20 years have revealed even more peculiar additions to the Star Wars cantina in the Malay Archipelago. The first of these was discovered in September 2003 at Liang Bua on the island of Flores by a team under the direction of Indonesian archaeologists Raden Pandji Soejono and Thomas Sutinka and Australian Michael Morwood. Nicknamed ‘the Hobbit’ because of its diminutive stature, its formal scientific name is Homo floresiensis. Standing only 1.1m high, this was the smallest member of the genus Homo ever described. The complex stratigraphy of the cave initially led to incorrect estimates that the Hobbits had lived as recently as 13,000 years ago, but later studies refined these estimates to between 200kya and 50kya - still remarkably late for such a primitive hominin, and raising the possibility that it had overlapped with modern humans in the Indonesian archipelago.

A more recent discovery from Callao Cave on the island of Luzon in the Philippines shows a similar diminutive body size. Homo luzonensis, as these creatures were dubbed, stood ~1.4m tall and had primitive features — skull morphology, hand anatomy, and tooth shape. The premolar teeth are particularly interesting, as they show similarities to robust Australopithecines such as Paranthropus. Dating to >50kya, and with nearby evidence of human butchering activity as much as ~800kya, they are clearly a very old species in the region, predating the arrival of modern humans. In order to arrive on Luzon they must have made an oceanic passage, likely from the island of Borneo.

The emerging picture of early human diversity in Southeast Asia presents a compelling case for a very early occupation by hominins even more archaic than Homo erectus. This runs counter to the traditional view that only erectus had the intelligence to adapt to life outside of Africa, but it is consistent with other emerging data from Africa and Eurasia. For instance, stone tools in China have been dated to 2.1mya, much earlier than any Homo erectus sites that have been found elsewhere on the continent. The recent discovery of human-like Oldowan stone tools at what appears to be a Paranthropus site in Africa also challenges the view that only humans were capable of making them. Careful analyses of H. floresiensis and H. luzonensis suggests they are more closely related to Homo habilis — or even Australopithecines such as Paranthropus. This might also help to explain the anomalous Meganthropus hominids, as they are in many ways similar to these robust Australopithecines.

There is an enormous amount of work still to do on the early human history of Southeast Asia, and the next decade promises to be an incredibly exciting time for paleoanthropologists working in the region. The evidence so far reveals tantalizing details that inform not only our understanding of Asian prehistory, but also perhaps the history of the entire hominin lineage and the timing of the initial exodus of human-like species from Africa.

Thank you Spencer!