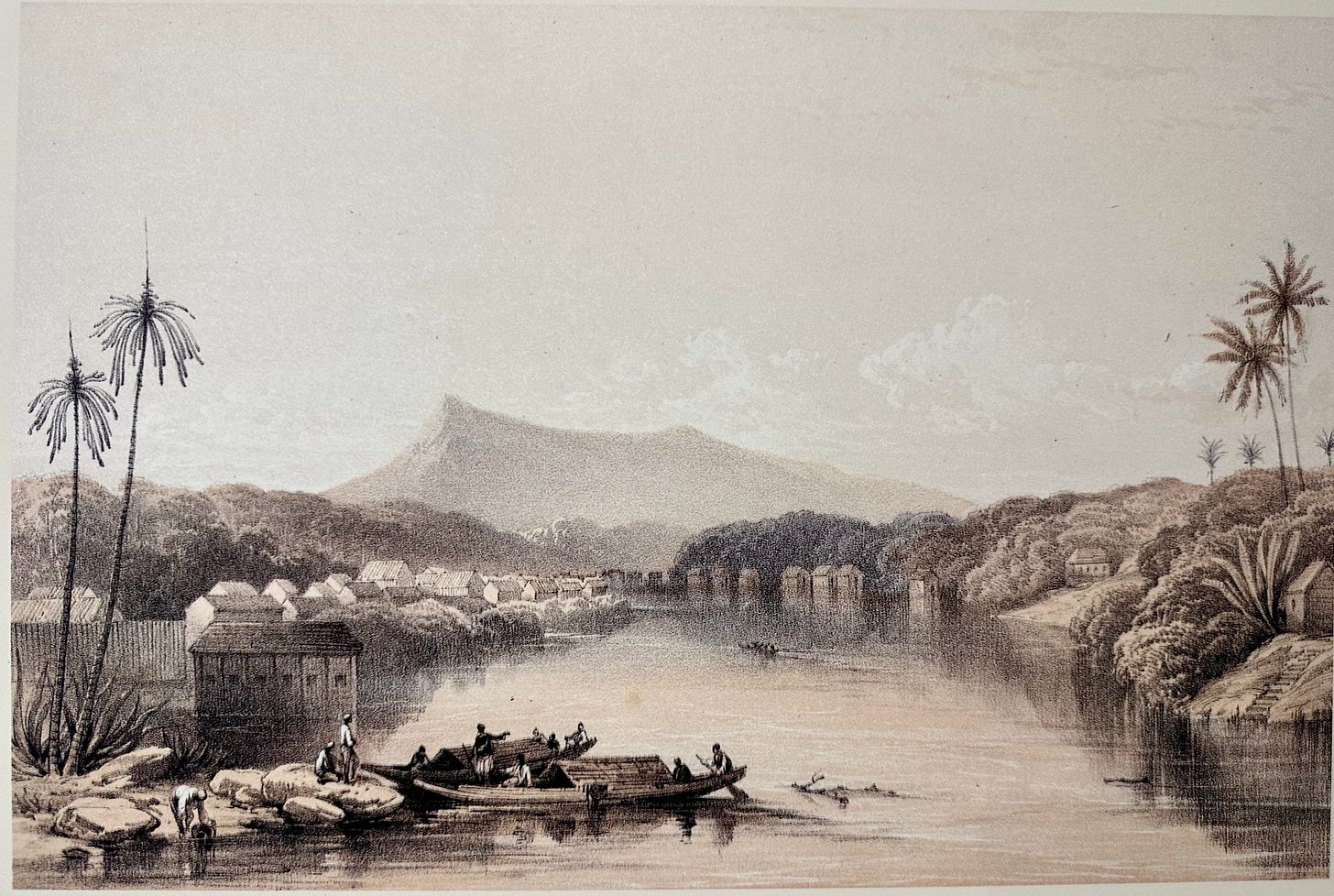

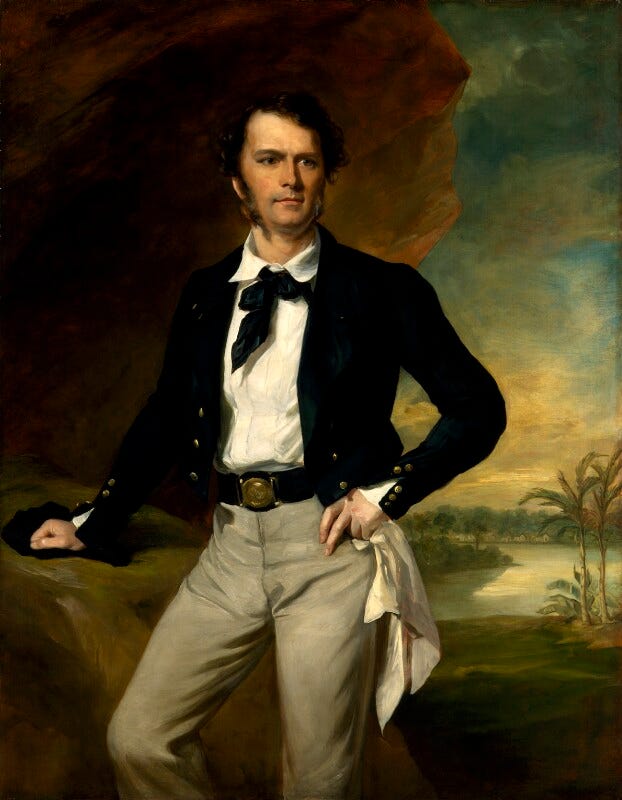

On the 15th of August 1838, a ship under the command of James Brooke sailed into the harbor of the trading port on Borneo’s Sarawak River (present-day Kuching). Brooke was 35 at the time, a former British army officer who had been seriously injured in India and given a military pension in his 20s. The scion of a wealthy family, his inheritance in 1835 had paid for his ship, the Royalist, as part of a plan to pursue a swashbuckling lifestyle in the Far East. Not much of a trader - as he discovered in a previous failed venture in Macao - James had set his sights on something far loftier: establishing his own colony, much in the mold of Sir Stamford Raffles. Borneo seemed to be a good place to cast his lot.

At the time, the Dutch claimed southern Borneo (present-day Kalimantan, part of Indonesia), while the Sultan of Brunei claimed the northern part of the island. The Brunei sultanate was something of a backwater in Southeast Asia, its rulers described succinctly by James Brooke’s biographer Nigel Barley:

The Royal House of Brunei, in the city known as Borneo Proper, divided its time equably between the traditional demands of fornication, murdering its relatives and Islamic piety.

The Brunei sultanate encompassed some of the most remote parts of the island of Borneo, and its primary trade at that time (before its vast petroleum reserves were exploited in the 20th century) was in metals such as tin and antimony, coal, and rubber and pepper from small plantations. The coastal settlements were populated by Malays from throughout the archipelago, as well as Chinese traders, while the inland parts of its territory were the realm of the Dayaks - a catchall name for the numerous Austronesian-speaking animist tribes native to Borneo, including the Iban and Bidayuh. The interior was only accessible via the many rivers flowing from the central highlands of Borneo to the coast, or on foot through the forests and mountains. Wild territory, to be sure, and the inspiration for many of Joseph Conrad’s books - Lord Jim is even based in part on the adventures of James Brooke.

The Brunei sultanate had long played the coastal Malays against the Dayaks, at the great expense of the latter, leading to long-established tensions between the two. These regularly erupted into armed clashes, and it was during one of these that Brooke arrived on the scene. In his self-assigned role as ‘enlightened colonial despot’, Brooke decided that he needed to step in to establish order and reduce the suffering of the Dayaks. This he did in a series of skirmishes along the Sarawak River over the subsequent two years, and the grateful Sultan of Brunei awarded him with Kuching and the surrounding territory in 1841. Brooke assumed the title of Rajah: head of state and ruler of Sarawak.

Over the subsequent six decades the Brooke Rajahs - Charles, James’ nephew and heir, became the second Rajah in 1868 - would gradually amass a huge amount of territory in Borneo, ultimately dwarfing the holdings of the Sultan of Brunei, which were reduced to a tiny enclave surrounding the capital city. The Brooke family would continue to rule Sarawak until the Second World War, when the Japanese invasion and subsequent postwar fallout would lead to the cession of Sarawak to Britain, adding to its holdings on the Malay Peninsula. Finally, in 1957 the Federation of Malaya would become an independent country with Sarawak as its largest state.

The history of the White Rajahs of Sarawak is fascinating in its own right, but it also intersects with the deeper history of Southeast Asia via the arrival of Alfred Russel Wallace in October of 1854 as a guest of James Brooke. Wallace and Brooke had met in Singapore earlier that year, at the beginning of the former’s journey through the Malay Archipelago, and Brooke invited Wallace to stay with him in Sarawak while conducting his fieldwork. Wallace would spend the next 16 months there, in the process cataloguing (and collecting) Borneo’s incredible biological diversity to a far greater extent than had ever been attempted before. He traveled deep inland, upriver and into the high interior mountains on foot, documenting new species such as the flying tree frog and the birdwing butterfly, and even adopting a baby orangutan orphaned when he killed its mother for a museum specimen. While in Sarawak he began to formulate his theory of evolution by natural selection, independent of Darwin, sketched out for the first time in his famous ‘Sarawak Law’ paper.

Wallace’s extended stay in Sarawak gave him time to learn many things about places he was unable to visit from discussions with local communities and other European explorers. Among the most interesting, perhaps, are the stories he heard of a huge cave in the northern part of Sarawak - then still part of the territory controlled by the Sultan of Brunei - where the locals found ancient animal and human-like bones. He even suggested (with his 19th-century racial bias) that it might even be useful for the study of human evolution:

It is not improbable that some human remains may also be found to throw light upon the question of the origin of the Malayan races, and to prove whether a Negrito or some still lower race was formerly spread over the whole archipelago.

Now known as the Niah Caves Complex, this site has proven to be arguably the most important in Southeast Asia for understanding the initial settlement of modern humans in the region. Based in large part on Wallace’s recommendation, the first survey of the site was conducted in 1878-9 by Alfred Hart Everett. Everett’s clearly perfunctory examination of the caves yielded nothing of interest, and it would be another 80 years before the caves were fully explored by archaeologists. And what a dynamic duo these archaeologists were.

Tom Harrisson was born in Buenos Aires in 1911, the son of a British railway engineer who was stationed there. The family returned to Britain at the outbreak of the First World War, but Tom’s parents returned to Argentina in 1919, leaving Tom and his brother in boarding schools. Tom later studied at Cambridge and Oxford, and led an Oxford expedition to Sarawak in 1932. In the late 1930s he co-founded a social observation project named Mass-Observation to study the lives of everyday Britons, and by the 1940s he was also a radio critic for British newspaper The Observer. During the Second World War he was a member of Z-Force, a special unit of the British Army tasked with recruiting Dayaks for Borneo to fight against the Japanese as part of Operation Semut.

In 1947 he settled into his long-term career as Curator of the Sarawak Museum, which had been established by Charles Brooke in 1888. He would remain at the museum for another twenty years, accumulating the finest collection of Bornean ethnological and natural history specimens ever assembled. The Harrisson Collection forms the core of the Sarawak Museum, including the newly opened Borneo Cultures Museum - the second-largest museum in Southeast Asia (after the National Museum in Bangkok).

Perhaps Harrisson’s greatest contribution to the study of human history, though, was to conduct extensive archaeological excavations at Niah Caves between 1954 and 1967 with his wife Barbara, whom he met when she served as a curatorial assistant at the Sarawak Museum. In 1958, while digging nearly 3 meters beneath the surface level of the cave in what they dubbed ‘Hell Trench’ because of the infernally hot conditions, Barbara discovered a human skull. Nicknamed the ‘Deep Skull’, it belonged to a teenaged modern human female. Initially dated to 45,000-39,000 years ago, it was the oldest modern human skeletal material ever discovered in Southeast Asia.

The remains from Hell Trench have recently been re-dated to ~35,000 years ago, and include a human femur that has enabled paleoanthropologists to assess the overall size of the young woman. The estimates of ~145cm in height and ~35kg in weight reveal her to be a very small, gracile individual most similar to the Aeta of the Philippines - a so-called ‘Negrito’ population of hunter-gatherers living on the island of Luzon. Although no DNA has been obtained from the Deep Skull remains, it is likely given their age and morphological affinities that she represented a Bornean population of the small-statured people who are likely to be among the earliest Homo sapiens in Southeast Asia, their descendants represented today by groups such as the Anadamanese, the Semang in Peninsular Malaysia, and the Aeta - and related to ancient Hoabinhian hunter-gatherers who lived in the region during the early Holocene starting ~10,000 years ago.

I’ll unpack the details of these population relationships and what they mean for the early migrations of modern humans in a future post, as part of my series on the prehistoric human settlement of Southeast Asia, but I do want to mention one more recent discovery that adds to the complexity of the early settlement of the region. Professor Darren Curnoe’s recent work at Trader’s Cave has demonstrated the presence of microlithic tools and human bone fragments dating to at least 65,000 years ago in the Niah Caves Complex. If confirmed, this will be among the earliest evidence of modern humans in the region - and tantalizingly, it suggests a modern human presence here at roughly the same time as our species’ exodus from Africa ~60,000 years ago. The details remain to be fully worked out, but Niah Caves continue to yield important insights into human prehistory, and reconstructing the tangled web of evidence demonstrates the extraordinary difficulty of synthesizing archaeology and genetics in this fascinating part of the world.

Highly recommended: The Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) has published an excellent multimedia overview of Darren Curnoe’s work at Niah Caves here: The bone hunters

I love reading your posts. Please make a book.

Great read. Thanks for the education on Kucing. I’ve just visited Liang Bua Cave in Flores where it was discovered a human species inhabited ~ 50,000 years ago.