“If you do not know history, you think short term. If you know history, you think medium and long term.”

― Lee Kuan Yew

This week Holly and I are in Singapore, stopping off for a few days en route to another destination to enjoy one of our favorite cities in the world. One of the things we love about living on Lombok is that we have inexpensive direct flights to two of Southeast Asia’s most vibrant cities, Kuala Lumpur and Singapore. This was by design. We enjoy being able to hop on a low-cost carrier for a quick getaway (AirAsia serves the KL route daily, Scoot has twice-weekly flights to Singapore), but didn’t want the tourist hub insanity of dozens of international flights every day like Bali. Singapore and KL are both major transportation hubs so there are plenty of international connections beyond that if we’re so inclined, all easily accessible from our relaxed home base on Lombok.

What’s so special about Singapore? One of the most futuristic cities in the world, its bold architecture - think Marina Bay Sands, the new Apple Store, or the Rain Vortex in Changi International Airport, consistently voted the best in the world - sits next to some of the most well-maintained heritage buildings in Southeast Asia. Add to this the world’s best botanical garden (it’s a toss-up with Kew of course, but to be able to see tropical plants in their natural environment outside of a glass house pushes Singapore into first place for me), one of my favorite museums in the world - the sublime Asian Civilizations Museum - and one of the world’s best food scenes, and you can see why we love living just a short hop away.

Singapore has a rich history - and not just since it became an independent country in 1965. Its status as one of the world’s great trading entrepôts dating back to at least the 13th century, when it starts showing up in Chinese texts as Danmaxi or Temasek. Its Malay name was Singapura, which comes from ‘lion city’ in Sanskrit: siṃha (सिंह) means ‘lion’, and pūra (पुर) means ‘temple’ or ‘city’. Singaporean scholars prefer Temasek as the name used for the pre-colonial city, so that’s what I’ll use here.

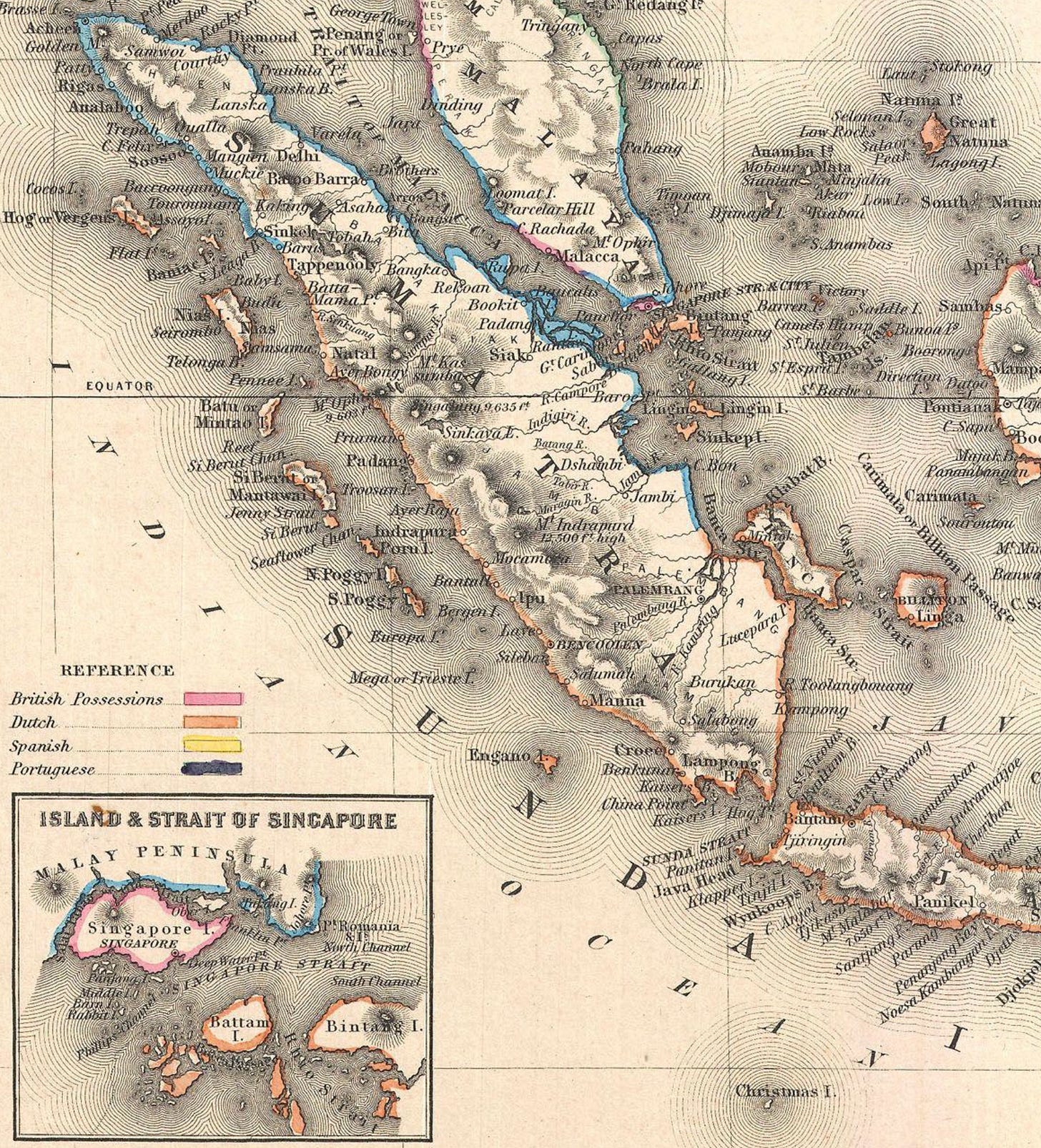

Singapore’s position at the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, at the entrance to the Malacca Strait - the key waterway that has connected East and West for the past two millennia, and still the world’s second-busiest shipping route - made it strategically valuable. Its importance was recognized by the great Asian empires of the 14th century, including the Chinese and Majapahit. The trade at that time consisted of a wide variety of goods, but perhaps the most important from the East were China’s silk and porcelain (a ceramic technology not duplicated in the West until the late 18th century by Josiah Wedgwood, Charles Darwin’s grandfather) and Indonesia’s spices. Western goods included spices and textiles from India, and frankincense and glass from the Middle East. It was rare to make the entire trip from one end of the Indian Ocean to the other, and early travellers like Marco Polo and Ibn Battuta brought back accounts that were often met with disbelief.

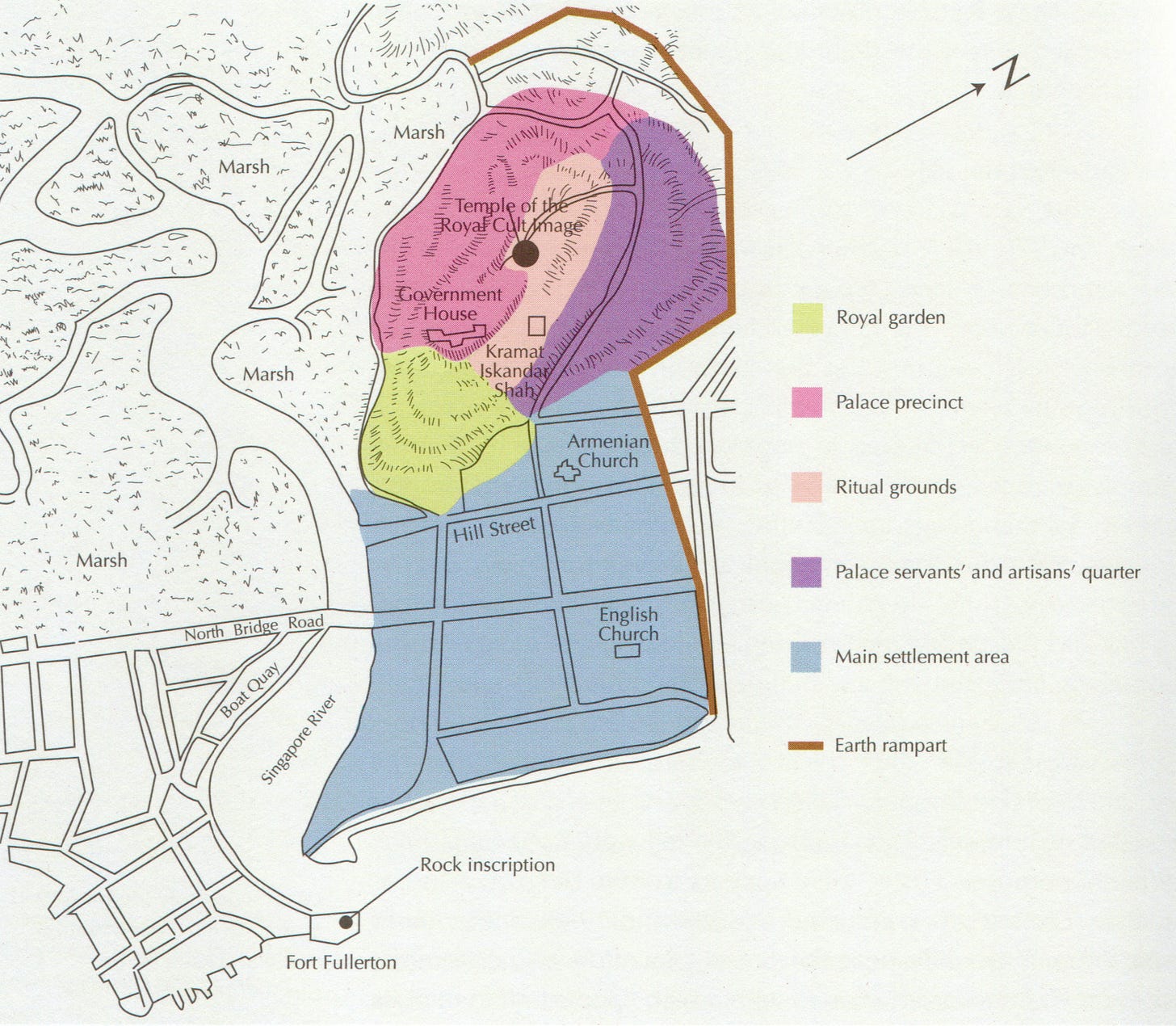

Archaeological evidence from the early Temasek settlement is fairly sparse, and mostly consists of small glass fragments and beads found in excavations on Fort Canning Hill in the southeastern part of today’s city. The hill itself, on the north shore of the Singapore River, is where the central religious and governmental complex of the Hindu-Buddhist city was located. Perhaps the best known artefact recovered from the area is the so-called Singapore Stone, a fragment sandstone from what had been a much larger boulder that was blown up by the British in 1843, found at the nearby mouth of the Singapore River. It is inscribed in a script thought to be Majapahit Kawi, and has been estimated to date from the 13th century - though it could be even older. Another well-known artefact is the gold jewelry engraved in Majapahit style found on Fort Canning Hill, thought to date from the 14th century. Beyond this, though, what we know of Singapore during these early days comes primarily from Chinese records.

During this time the dominant power in the region was the Hindu-Buddhist Majapahit empire, which controlled the spice trade through the Malacca Strait from their base on Java. The Majapahit had ports on both sides of the strait in Sumatra and on the Malay Peninsula, but by the 15th century another power had assumed local control: the Malacca Sultanate. Based in the present-day port of Malacca (Melaka in Malay) ~200km northwest of Singapore, the Sultan of Melaka controlled trade through the Malacca Strait for over a century until its conquest by the Portuguese in 1511. Singapore largely faded into obscurity for four centuries after this, a small village of perhaps a few hundred people used primarily by the Orang Laut, pirates and seasonal traders. The Portuguese, followed by the Dutch and the British, would control trade through the strait from Malacca and later Penang.

Singapore’s real entrance onto the international scene happened in 1819 when Sir Stamford Raffles, Lieutenant-Governor of the British colony of Bencoolen on the southwest coast of Sumatra (and former Lieutenant-Governor of the Dutch East Indies after he seized western Java from the Dutch in 1811), signed a treaty with Hussein Shah, the Prince of Johor, a territory that included southern Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore. The goal was to establish a significant British presence at the mouth of the Malacca Strait, consolidating Britain’s control of maritime trade between East Asia and India, which was already controlled by the British East India Company. Singapore would remain a British colony until independence in 1965.

With its mix of sailors and traders from throughout the region, early colonial Singapore was a wild place with opium dens, gambling parlors, prostitutes and Chinese secret societies; there is a documentary on YouTube about what life was like in the early colony that is well worth a watch. Needless to say, in those days the settlement was a far cry from today’s efficiently regulated city-state. Nonetheless, its status as a free port - levying no duties on goods trans-shipped through it - made it wildly popular with Asian traders. The population would quadruple to more than 60,000 by the 1860s, but with little in the way of infrastructure put in place by the East India Company to deal with the growing population it became increasingly unruly.

The situation eventually became so dire that the British government removed administration of the colony from the Company in 1867, declaring Singapore a Crown Colony under direct control of the British government. The latter half of the 19th century and the first quarter of the 20th would see Singapore come into its own as a European colonial outpost and trading center, and much of the colonial architecture that you see in the city today dates from this time. Perhaps most famous is Raffles Hotel, named after Singapore’s founder but built and operated by the Sarkies Brothers, a successful Persian-Armenian family that would eventually own an empire of high-end hotels throughout Southeast Asia, from Burma to Java. Opening in 1887, it was the epitome of colonial elegance in Singapore, and remains so today.

Singapore was captured by the Japanese in 1942 during the Second World War, and the British failure to defend the colony led to considerable unrest following the Japanese surrender in 1945. The inexorable postwar slide toward independence would eventually culminate in internal self-rule in 1959 and full independence in 1965. The Singaporean who oversaw this transition and architected the new city-state was Lee Kuan Yew, one of the most influential world leaders of the 20th century. Equal parts strongman and technocrat, LKY created the blueprint for modern Singapore’s success, and his People’s Action Party still rules Singapore to this day, despite viable opposition parties and free elections.

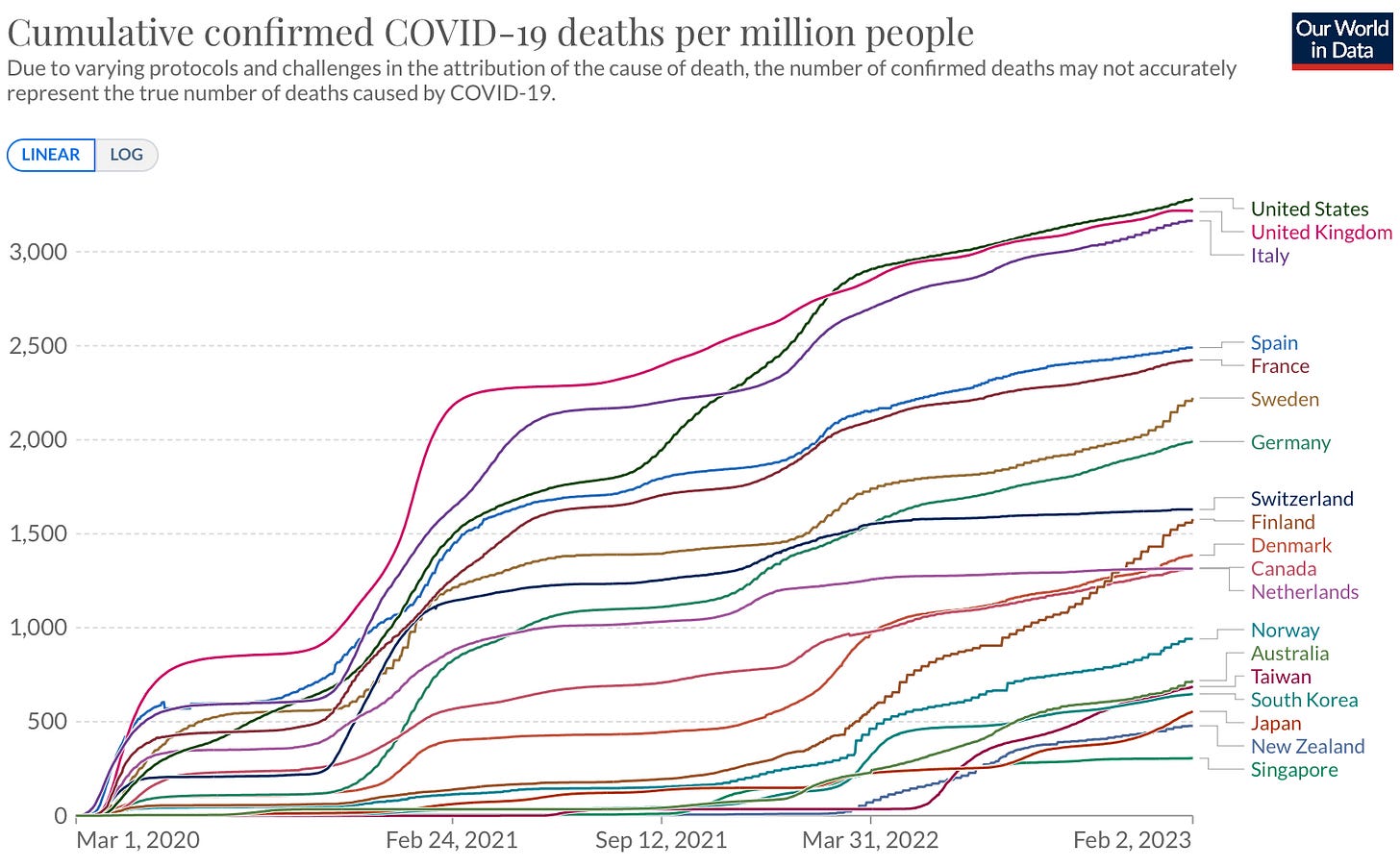

Modern Singapore’s undeniable success - it’s the second richest country in the world after Luxembourg, and its life expectancy rose from 66.8 at independence to 84.3 in 2023 - world-leading infrastructure and sound governance equipped it very well for the Covid-19 pandemic. Based on my experience there during our last visit in February/March 2020, I wrote a piece for MIT Technology Review early in the pandemic arguing that Singapore’s Covid-19 response was a model for other countries to emulate. This has in fact been borne out by the data: Singapore has had the lowest number of Covid deaths per capita of any rich country in the world. If this is any indication, I suspect it is likely to handle the existential challenges of the 21st century (particularly climate change) with similar success. A country with a deep and fascinating past, but also - perhaps - one that can show us the best way to navigate our way into an uncertain global future.

Bibliographical note: The award-winning Seven Hundred Years: A History of Singapore is highly recommended for the early history of Temasek and colonial Singapore - probably the best single-volume overview available.

Singapore is one of my favorite cities too. We lived there 2005-2006 and enjoyed it tremendously. (I cried when it was time to leave.) Food, culture, people, safety, cleanliness, healthcare...all superlative. Thanks for sharing this post.