In February-March this year I traveled to Singapore, Sarawak and Jakarta - the first because Holly and I love visiting the Lion City (luckily it’s one of the two international destinations we can fly to directly from Lombok), and then onward to Sarawak to scout for an upcoming trip. This was followed a couple of weeks later by a quick overnight to Jakarta to run an errand. I’m a serious museum junkie, and with three of my favorites in these locations I was in heaven.

Modern museums date back to the collections of artefacts kept by Renaissance-era European collectors. Of course, people with the means to do so have always hoarded interesting treasures, but these private ‘cabinets of curiosities’ (Kunstkammer in German) formed the cores of many famous museums around the world today. Peter the Great’s Kunstkamera, opened to the public in 1714, was the first museum in Russia, and Sir Hans Sloane’s collection formed the basis of the British Museum when he bequeathed it to the nation upon his death in 1753.

Museums in Asia primarily date back to the European colonial era. The Indian Museum in Kolkata is the oldest, founded in 1814. Sir Stamford Raffles, founder of Singapore, collected his own Kunstkammer in the 19th century, and it later formed the core of the National Museum of Singapore, founded in 1887, and later the much newer Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum and Asian Civilisations Museum (ACM). All are wonderful places to explore the history, both natural and human, of the region - but the ACM is by far my favorite of the three.

Although it only dates to 1997, the ACM is housed in the beautiful colonial-era Empress Place Building on the north shore of the Singapore River, which makes it seem far more venerable. As “the only museum in Asia with a pan-Asian scope”, it is an extraordinary place to spend an afternoon getting a quick overview of the complex cultures of the region. Through its exhibits you get a clear sense of how Southeast Asia is the ‘melting pot’ of Asia, with influences from the Arabian Peninsula, India and China mixing with indigenous Malay and other cultures to create the dizzying mix you find in the region today.

And dizzying it is for most — if you don’t know your Mahābhārata from your Majapahit or Malay, it’s worth reading up on some of the pre-colonial history of the region before visiting. I’ll be covering some of these cultures in upcoming posts, and there are a number of books that present the material for specific regions in scholarly detail, but I’ve yet to find a single-volume, easily-accessible overview of precolonial Southeast Asian history (probably the best option would be the Brief History series on individual countries).

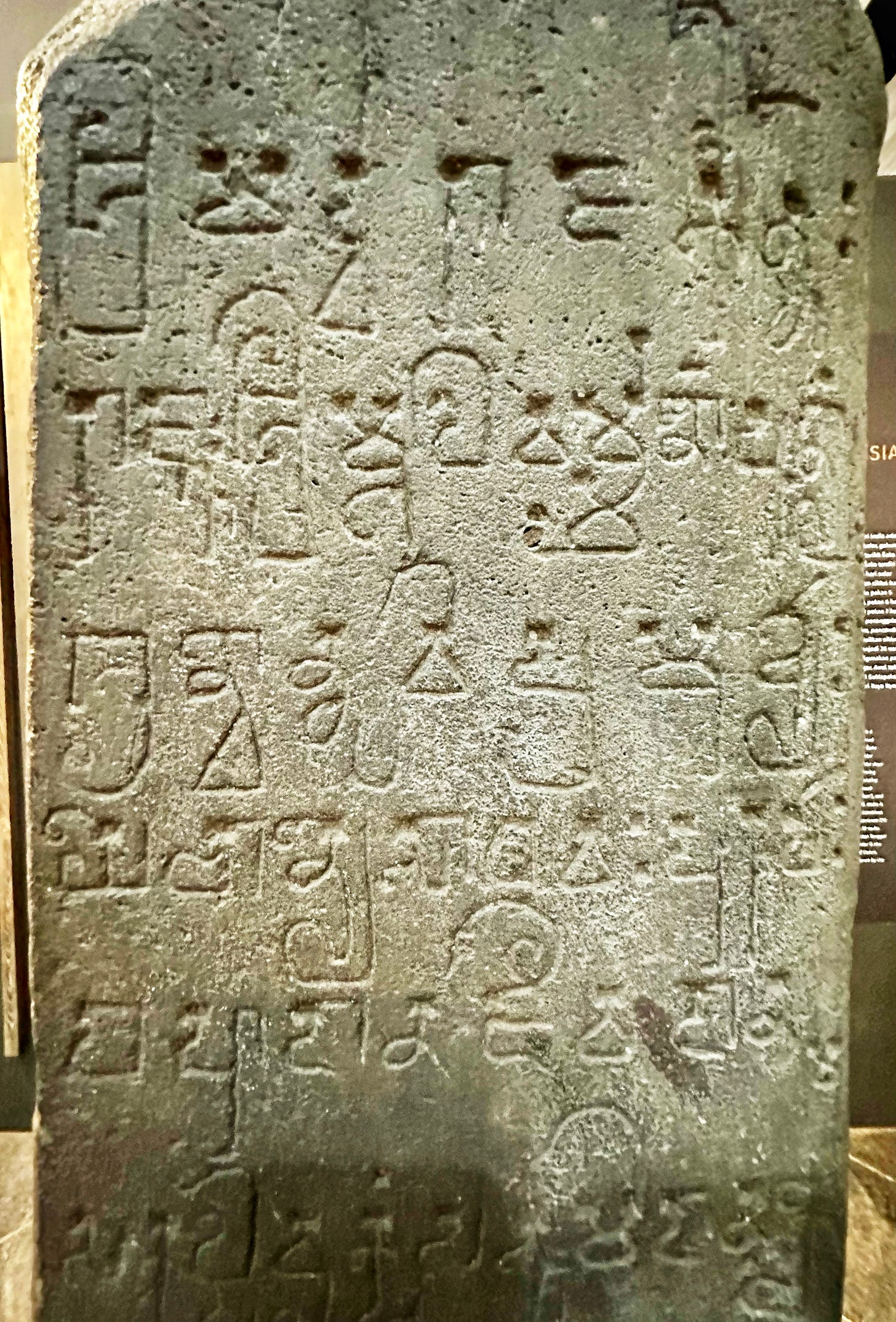

The first exhibit you encounter when you enter from the ticket counter is also one of its most important — the famous Belitung shipwreck, discovered in Indonesia in 1998. Dating to the Chinese Tang dynasty, it’s an Arabian dhow that sank in a storm off Belitung Island to the southeast of Singapore in ~830 CE. It was returning from a voyage to China with a cargo of ceramics and gold intended for traders in the western Indian Ocean, and represents the largest collection of Tang-era artefacts ever discovered outside of China.

The initial display is impressive, with ceramic bowls arranged in the shape of a wave, with a model of the ship to the far left. The fascinating aspect of the ceramic finds is how they were manufactured to order for western consumers at factories in southern China, entirely for export — some 60,000 items attesting to the massive scale and desirability of China’s manufactured goods in the 9th century. This theme is continued throughout the rest of the museum, where you can see many other examples of the ancient trade between East and West along this ‘Maritime Silk Route’.

The collection is vast, and can easily occupy a full day of exploration. One of the most fascinating pieces for me was the ampang bilik from Tana Toraja in Sulawesi. The Toraja people, while nominally Christian, practice an ancient form of ancestor worship that was once far more common throughout the Austronesian world. When someone dies, the Torajan family keeps the bodies in the back section of their houses until they can afford a huge ceremony at which many water buffalo are sacrificed. The bodies are eventually buried in hand-cut rock chambers high up on a cliff face, with wooden effigies of the person perched in front of them. Before that happens, though, the bodies can spend months — even more than a year — residing in the back of the house. In between this back room and the front of the house is a carved ritual gateway intended to represent the dividing line between the world of the living and that of the dead - the ampang bilik.

Our next stop after Singapore was Kuching, the capital city of the Malaysian state of Sarawak, which I’ve written about in a previous post. A quick 1-hour flight across the South China Sea from Singapore, this city of ~400,000 is often referred to as the ‘gateway to Sarawak’, and is a popular weekend getaway for Singaporeans looking to take in its delicious food scene and rich history, as well as a base for more adventurous travelers looking to head into the interior of Borneo. We strolled around the waterfront along the Sarawak River, ate many helpings of spectacular Sarawak laksa, and explored the fascinating Brooke legacy — but probably the highlight was the new Borneo Cultures Museum, which opened in March 2022.

Billing itself as the second-largest museum in Southeast Asia, it has an incredibly impressive collection of artefacts from the local Dayak tribes, as well as a fascinating section on the earliest inhabitants of Borneo, discovered in the Niah Caves in northern Sarawak. The overview of the caves and their importance were a great amuse-bouche before my visit to Niah a few days later. The core of the collection is from the nearby Sarawak Museum, founded in 1888 by Charles Brooke.

The Dayak artefacts comprise one of the most extraordinary ethnological collections in Southeast Asia. These Austronesian-speaking peoples live throughout Borneo, dominating the interior, but with many groups scattered along the coast as well. Some still live in traditional longhouses, a village of hundreds of people dwelling in a single gigantic wooden structure, with communal living and cooking spaces and subdivided family sleeping units. Other tribes were hunter-gatherers until very recently, though most are now settled in sedentary villages. Dayaks famously practiced headhunting, although this ceased in the 20th century because of government intervention.

Overall, the Borneo Cultures Museum is a fantastic addition to the major museums of Southeast Asia, and is housed in a beautiful building with modern takes on traditional design elements that create a gorgeous space to display this hugely important collection.

The final museum in my trio was the National Museum in Jakarta, which I had only visited once before, hurriedly squeezed into a hectic day in Jakarta. There are many national museums in Southeast Asia — Bangkok’s National Museum is outstanding — but Indonesia’s National Museum comprises an absolutely enormous collection of ~70,000 aretefacts from the largest country in the region, spanning an unparalleled temporal range from the earliest hominins in Southeast Asia ~1.8 MYA up to the 20th century.

The collection is overwhelming enough for first-timers that a guided tour is definitely worth it, particularly if you’re not acquainted with Indonesian history. On this trip I booked with the outstanding Indonesian Heritage Society a few days before my visit, and enjoyed bantering with my Indian guide (she moved to Jakarta from India with her husband and family a decade before) about the exhibits and some of the omissions in the display descriptions. Thoroughly enjoyable, and worth it even if you already know your Gajah Madah from your gamelan.

One of the joys of seeing objects in Southeast Asian museums, whether in Jakarta, Kuching or Singapore, is seeing the citizens of the countries that created the objects viewing their own history. Unlike a western mega-museum such as the British Museum, where the majority of the objects are removed from their countries of origin (hopefully to be repatriated at some point as curators worldwide seek to decolonize their collections), in these museums you can see local people learning about their own history and culture — in the case of Southeast Asia, a rich, syncretic blend of indigenous, Indian, Chinese, and Arab influences that has combined to create the fascinating tapestry of diversity you find in the region today.

Strong agree on ACM!