Happy New Year! I will be doing a special post next week for my first Substack anniversary, but this is one of several upcoming deep dives (quite literally in this case) into some of the fascinating places I visited during my expedition across Wallacea in 2023. I hope you enjoy it, and that you had a wonderful holiday break.

After reading about Lake Matano for the past couple of years while planning my expedition through Wallacea, it was a genuine pleasure to finally arrive there in August and be greeted by such an awe-inspiring sight. The scale of the lake is massive, and with forest-covered mountains rising up all around and mist hanging low over its surface during rainy weather (there were intermittent showers every day when I was there) it’s positively magical. I hadn’t been to such a huge lake in years — the last time was in May 2019 when I spoke at a conference in Montreux, on the northern shore of Lac Léman. The Swiss lake is over 3x larger, but Matano is far deeper at ~600m. In fact, it’s the deepest lake in Indonesia, the deepest island lake in the world, and the 11th deepest lake in the world overall.

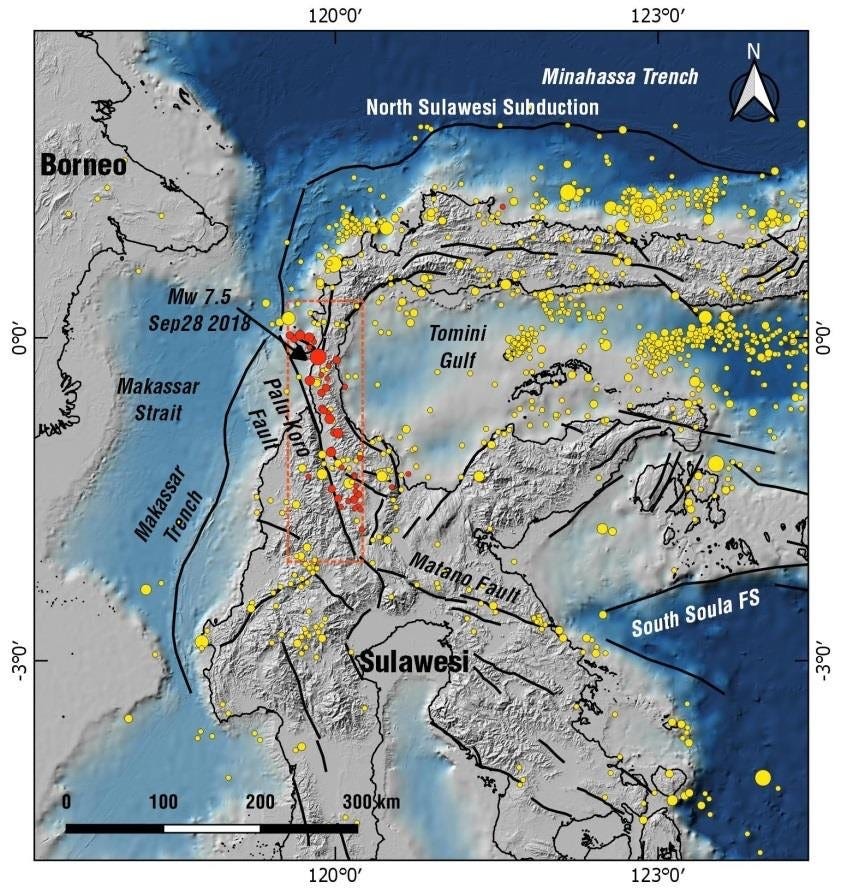

Why so deep? It has to do with the way the lake was formed. Matano is part of the Malili lake system, a series of five interconnected lakes in east-central Sulawesi. Unlike most lakes in Indonesia, which are found in the calderas of dormant or extinct volcanoes like Toba, the largest lake in the country, Matano was formed through the action of plate tectonics — in particular, the spreading apart of two plates, creating a deep fissure between them. Over time this rift valley has filled with water, and the end result is today’s Malili lakes. Like the Rift Valley lakes of Africa — Victoria, Tanganyika and Malawi among them — and Lake Baikal in Siberia, the Malili lakes are fascinating bodies of water.

Lake Baikal contains largest volume of fresh water in the world, with more than 20% of the total. It is also the deepest — at 1642m — and oldest lake in the world, forming some 25-30 million years ago. For this reason, it contains many endemic species that have evolved in the depths of its crystal-clear waters over a long period of time, including the famous Baikal seal, known locally as nerpa. The African Rift Valley lakes, while not nearly as old (the oldest dates back 10 million years or so), are characterized by many interconnected bodies of water with a huge number of endemic species, especially cichlids. These fish have undergone a massive adaptive radiation as they have colonized new lake environments with varying ecologies, resulting in more than 850 species in Lake Malawi alone.

The Malili lakes in Sulawesi also have a well-studied adaptive radiation of fish known as sailfin silversides, belonging to the family Telmatherininae, which have diverged into dozens of species over the past 1 million years or so as they have colonized the lakes and the rivers surrounding them. This complex evolutionary laboratory is being threatened by environmental degradation, especially from the Sorowako nickel mine — the largest in nickel-rich Indonesia — along the southern shore of Lake Matano, as well as a population explosion of introduced flowerhorn cichlids alien to Sulawesi. Interestingly, there are crocodiles in the Malili lakes that have migrated upriver from estuaries near the coastal town of Malili. While I didn’t see any when I was there, I was assured that populations still lurk in the less-visited recesses of the lakes.

The Sorowako nickel mine brings me to the main theme of this post. Mining has long been the primary industry in the Matano region, with valuable minerals exposed due the intense tectonic activity. Today it’s nickel, one of the key components in the rechargeable batteries essential in the global transition to a ‘green economy’, but historically it was high-quality iron. 17th century Dutch chroniclers of the colonial enterprise in Indonesia wrote about the iron they associated with the Kingdom of Luwu, which at that time controlled its trade with the outside world from Lake Matano:

Luwu…lay in a remote corner of island Southeast Asia, and was free of direct colonial interference until very late in the nineteenth century. Early European visitors were aware of the high-quality iron coming out of Luwu, but apparently made no attempt to seize control of its trade, presumably as iron could be imported reasonably cheaply from Europe as ballast. The earliest source to mention the export of iron from Luwu is Speelman (1670). Writing in the same century, the blind naturalist Rumphius declared that the iron produced at Lake Matano was practically as good as steel, and that one single Lake Matano sword was worth six swords from Bunku in Central Sulawesi (Beekman 1999:238). Until the early twentieth century, iron tools made at Lake Matano were traded to Maluku, and Lake Matano iron ore was exported as far as northern Sumatra….

(source)

The reason for the high quality of the iron was the trace metals contained in the ore, including chromium, manganese, cobalt, as well as the abundant nickel mined there today.

While Luwu — one of several of Bugis kingdoms in South Sulawesi that I’ve discussed in a previous post — did indeed control the export of the high-quality iron to the rest of the Indonesian archipelago, the region around the lake was inhabited by a very different people: the Rahampu’u. Belonging to a completely different ethnolinguistic group, speaking languages belong to the Celebic division of the Austronesian language family, the Rahampu’u are proud of their ancient history as master ironsmiths. The Luwu kingdom may have grown rich from trading their handiwork, but the iron mines were built and run by the Rahampu’u.

Knowledge of the high-quality Matano iron elsewhere in the Indonesian archipelago dates back much further than the Dutch colonial period, of course. It was actually this high-quality iron that gave the island of Sulawesi its name — a combination of sula (‘island’) and besi (‘iron’, which has morphed into -wesi in modern Indonesian, though the older form remains in the original Portguese name for the island, Celebes). The earliest mentions of it are during the Majapahit era (1293-1527 CE). The Majapahits, based in eastern Java, were one of the dominant empires of medieval Southeast Asia. Their foundation story is fascinating, and the expansion of their power across the far-flung islands of Indonesia created a medieval precursor to the modern country of Indonesia.

Biologists have a saying that ‘nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution’, first coined by evolutionary geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky (my ‘academic grandfather’, as he was the doctoral advisor of my doctoral advisor) in an essay he published in 1973. A historical corollary of this might be that ‘nothing in the 13th century makes sense except in the light of the Mongols’: 13th century Eurasia was indelibly marked by their overarching presence. Expanding out of the remote mountains and plains of Mongolia in the early part of the century, the Mongol cavalry under Genghis Khan rapidly conquered the wealthy cities of the Silk Road in Central Asia. By the time of Genghis’ death in 1227, Mongol rule extended from the Pacific Ocean to the Caspian Sea. Under the command of his son Ogedei, the Mongols expanded the empire to include Persia and Northern China, and under Ogedei’s cousin Kublai they eventually expanded westward into Europe (briefly). It is their expansion southward into China, though, that matters for our story. When Kublai founded the Chinese Yuan Dynasty in 1271, the Mongols at last completely controlled the valuable transcontinental trade along the Silk Road between East and West, becoming the largest land empire the world had ever seen.

Not content with his terrestrial victories, Kublai soon turned his attention to the maritime realms to the east and south of China. At this point he ran into serious problems, in part because the islands and tropical jungles they were expanding into weren’t as amenable to the Mongol methods of mounted warfare. Attempted invasions of Japan in 1274 and 1291 both ended in failure, with weather conditions at sea playing a significant role — especially the famous kamikaze (‘divine wind’) waves that wiped out the Mongol forces in their second attempt. Mongol expeditions in Southeast Asia were similarly ill-fated, with failed invasions of several of the region’s kingdoms.

Kublai first sent emissaries to the court of Singhasari, the dominant power on Java, in 1289. One of several small Javanese kingdoms vying for control of the spice trade in the power vacuum left by the decline of the earlier Srivijaya empire (which had been based in Sumatra and was the most powerful regional kingdom from the 7th-11th centuries CE), Singhasari was ruled by King Kertanegara, a proud man who considered himself to be a divine reincarnation of Shiva and Buddha. He thought it laughable that the distant Mongol khan expected him to submit to Yuan rule and pay tribute, and promptly disfigured the emissaries by cutting off their ears and branding their faces before sending them packing, back to Kublai and the Yuan court.

Kublai, needless to say, wasn’t pleased. After three years of preparation, the invading Mongol army arrived at Kertanegara’s Javanese capital in 1292 aboard 1000 ships. In the meantime, though, Kertanegara had been killed by a rival kingdom, the Kediri, in a power struggle. The sole surviving heir to the Singhasari throne was Kertanegara’s son-in-law, Raden Wijaya. Sensing an opportunity to both defeat his Kediri enemies and the invading Mongols, Raden Wijaya agreed to Mongol demands for tribute if they would help him defeat the Kediri and install him on the throne as their vassal. The Mongol commander fell for the deception, and a bloody battle ensued in which the Kediri were defeated. After their defeat, Raden Wijaya’s forces turned on the remaining Mongol expeditionary force. Far from home in an unfamiliar land, depleted from the battle with the Kediri, confused by Raden Wijaya’s subterfuge, and conscious that the monsoon was about to shift (which would have left them standed in Java for another six months), they decided to cut their losses and headed back to China. Raden Wijaya had defeated both his Javanese rivals and the invading Mongol army.

The new king immediately set about consolidating his power on Java. The remainder of Raden Wijaya’s rule was spent battling Javanese rivals from his capital, which he named Majapahit. He died in 1309 and was succeeded by his son, Jayanegara. A weak king with a penchant for marrying his half-sisters who experienced several attempted rebellions during his rule, Jayanegara’s only lasting impact was to promote a soldier named Gajah Mada to a senior role at court. Jayanegara was eventually killed by his own court physician in 1328, perhaps in part as retribution for the king seducing his wife. With no heirs, the Majapahit court was in limbo for a few years until Gajah Mada was eventually appointed prime minister in 1336.

It was under Gajah Mada, especially during the reign of King Hayam Wuruk (1350-1389), that the Majapahit kigdom began an ambitious expansion — not only westward, into the ancient Srivijaya strongholds on Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula, but also northward into Borneo and into the many far-flung eastern islands of the archipelago. Gajah Mada famously took the Palapa oath, saying he would not rest (‘enjoy spice’) until he had brought the disparate islands of the Indonesian archipelago (Nusantara in Old Javanese) under Majapahit control. This he did, creating the first semblance of what would later become the country of Indonesia.

While controlling the trade in spices from Maluku was critical for international trade, the renowned iron from Lake Matano was also high on the list for domestic use. The Majapahit ability to harness all of the rich resources throughout the far-flung Indonesian islands made them the most powerful kingdom in Southeast Asia, their suzerainty extending from southern Thailand to the island of New Guinea.

The past few years have seen a renewed interest in the archaeology of the Matano region, led in large part by David Bulbeck’s group at the Australian National University. His colleague Shinatria Adhityatama has led excavations of several of the ancient sites around Lake Matano, most of which are underwater. Because of the nature of the lake, situated in the middle of an active tectonic fault, sections of the shore are shaken loose and settle underwater during earthquakes. Perhaps the most famous site, Pulau Ampat (‘Four Islands’), is found on the southwestern side in a few meters of water. Shinatria and his colleagues have found evidence of ironworking at the site dating to the 8th century CE, revealing the ancient tradition of iron working by the Rahampu’u people — long predating the Luwu kingdom, as well as the Majapahit.

One of my goals at Lake Matano was to dive the submerged archaeological sites. Unfortunately, many have now been picked over by treasure-seekers and the section of the lake where the richest sites are found, including Pulau Ampat, is off limits to divers. It is possible to get special permission from the Rahampu’u king (Mokole Wawainia Rahampu’u), but unfortunately he was in Jakarta during my visit lobbying for government protection for the lake. I did meet with his son, Tareh, who was incredibly generous with his time and took me out in his boat to dive some of the other locations where artefacts aren’t visible on the lakebed. I hope to return to the lake soon to dive Pulau Ampat, but even the dive I did nearby was interesting, and you can clearly see how earthquakes have dislodged huge sections of the former shore and submerged them — they look like vast staircases leading down to Matano’s murky depths.

Tareh invited me to visit his father’s home on the morning I was leaving Matano, in order to see part of the incredible collection of artefacts that have been recovered from the lake over the years. In a basement room are spear points, knives, arrowheads and other museum-worthy pieces. It was a rare treat, and contained many examples of the exquisite ironwork that the Rahampu’u have produced over the past twelve centuries, still intact after all those years of immersion in the lake — a perfect ending to my visit to this fascinating and beautiful place.

Cool... Now, we develop a geopark for this area called geopark matano & lake malili system

Fascinating stuff. Thanks Spencer.