This is the first of several posts about my rail journey across Java last summer.

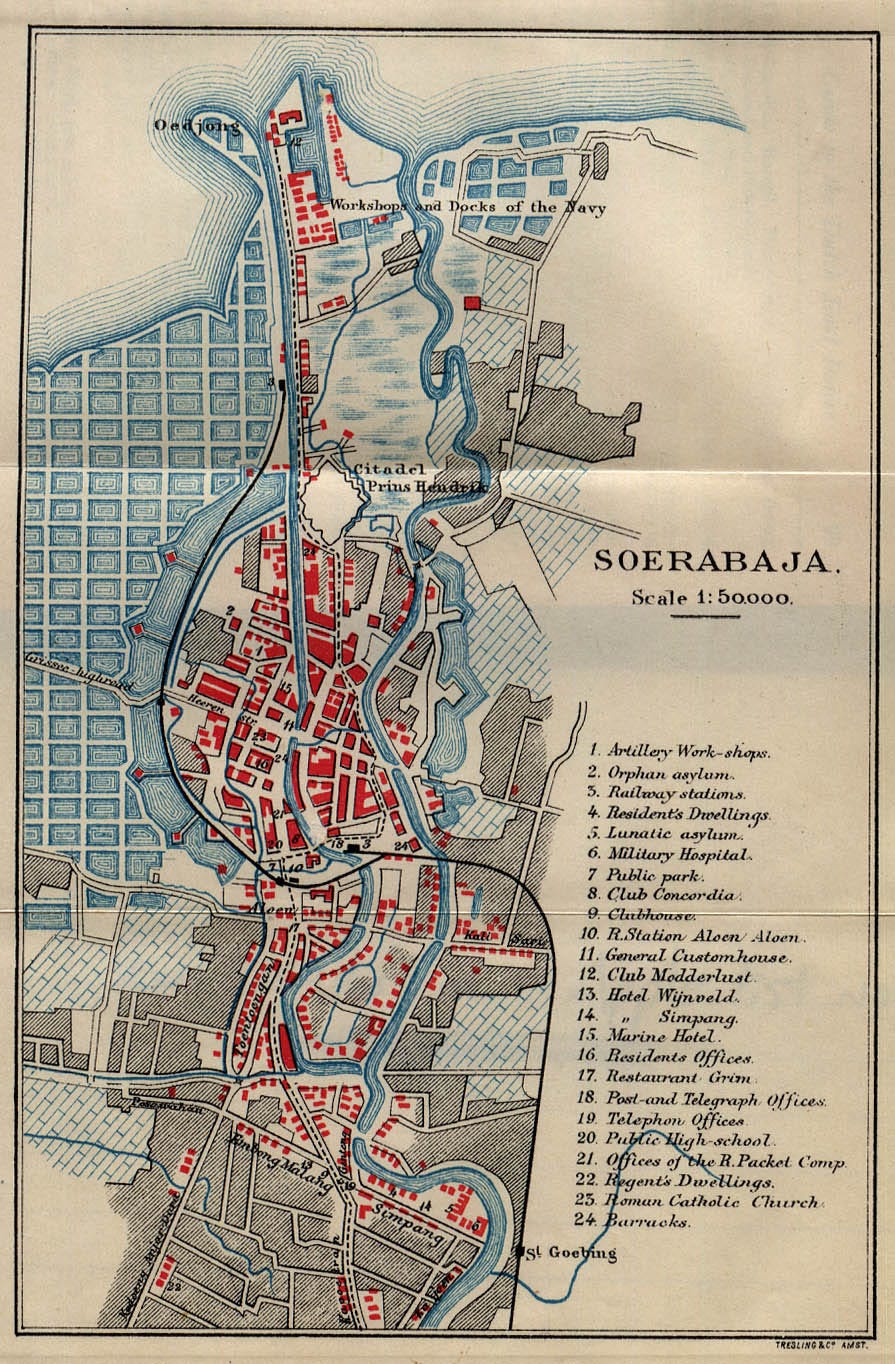

Surabaya is a river city, in the same sense as New Orleans or Shanghai — a port city built where a major inland waterway enters the sea (the Mississippi in the case of the former, and the Yangtze — longest river in Eurasia — in the latter). The canals cutting through today’s densely-populated Surabaya are the domesticated remnants of ancient river delta tendrils, artificially constrained so that a city could be built. With the shelter provided by the island of Madura, just off the coast in the Java Sea, Surabaya is a natural port — Indonesia’s second-largest, in fact. The Dutch recognized its strategic location in the 18th century when they seized the area and created the core of modern Surabaya, but it had been the gateway to the interior of eastern Java for nearly a millennium before that.

The river that feeds this ancient port is the Brantas, second longest on Java after the Solo. Flowing in an idiosyncratic circular direction, the Brantas arises on the slopes of the great volcanoes just south of Surabaya, coalescing into a river near present-day Malang. It then meanders southward and westward from there to Tulungagung, then turns northward along the western slopes of the volcanoes before heading eastward past Mojokerto to its delta on the Java Sea.

It’s difficult to navigate up the Brantas from bustling Surabaya by boat these days, but the railway traces roughly the same route. The journey is an easy one: I hopped on a train at Gubeng station, taking the Argo Wilis — overkill for such a short journey as it’s intended for comfortable trips all the way to Bandung in West Java, but there are several train options each day to choose from. About half an hour later I stepped onto the platform at Mojokerto. Renowned by paleoanthropologists as the location where the oldest Homo erectus discovered in Java was unearthed in 1936 (dated to between 1.5-1.8 MYA), my goal was not to see the ancient hominins that once lived there. Rather, I was headed for the nearby town of Trowulan, a 20-minute cab ride to the southwest from the station.

Trowulan is the site of the capital of the medieval Majapahit Kingdom, the most powerful empire in pre-modern Indonesia. It has a fascinating origin story, which I recounted in my post on the iron mines of Lake Matano:

Kublai [Khan] first sent emissaries to the court of Singhasari, the dominant power on Java, in 1289. One of several small Javanese kingdoms vying for control of the spice trade in the power vacuum left by the decline of the earlier Srivijaya empire (which had been based in Sumatra and was the most powerful regional kingdom from the 7th-11th centuries CE), Singhasari was ruled by King Kertanegara, a proud man who considered himself to be a divine reincarnation of Shiva and Buddha. He thought it laughable that the distant Mongol khan expected him to submit to Yuan rule and pay tribute, and promptly disfigured the emissaries by cutting off their ears and branding their faces before sending them packing, back to Kublai and the Yuan court.

Kublai, needless to say, wasn’t pleased. After three years of preparation, the invading Mongol army arrived at Kertanegara’s Javanese capital in 1292 aboard 1000 ships. In the meantime, though, Kertanegara had been killed by a rival kingdom, the Kediri, in a power struggle. The sole surviving heir to the Singhasari throne was Kertanegara’s son-in-law, Raden Wijaya. Sensing an opportunity to both defeat his Kediri enemies and the invading Mongols, Raden Wijaya agreed to Mongol demands for tribute if they would help him defeat the Kediri and install him on the throne as their vassal. The Mongol commander fell for the deception, and a bloody battle ensued in which the Kediri were defeated. After their defeat, Raden Wijaya’s forces turned on the remaining Mongol expeditionary force. Far from home in an unfamiliar land, depleted from the battle with the Kediri, confused by Raden Wijaya’s subterfuge, and conscious that the monsoon was about to shift (which would have left them standed in Java for another six months), they decided to cut their losses and headed back to China. Raden Wijaya had defeated both his Javanese rivals and the invading Mongol army.

Following this extraordinary series of events, Raden Wijaya established his capital at present-day Trowulan, naming the kingdom Majapahit after a tree that grew there with a ‘bitter fruit’ (maja pahit).

Today, very little remains of what must have been an impressive city. Based on surveys carried out in 1815 on the orders of then-governor of British Java Thomas Stanford Raffles (who would later found Singapore), it was thought to be a rather modest settlement of ~ 7.5 km2, inhabited by perhaps 10,000 people (it’s now thought to have been a more extensive settlement). But as the capital of a thalassocratic kingdom that drew power from its control of maritime trade routes, Trowulan likely would have been a largely residential and administrative seat for the king and his senior officials. The kingdom’s real power lay on the waves of the Java Sea and beyond, and in particular the trade connections to the vast network of vassal islands throughout the Indonesian archipelago: spices, iron and exotic forest products from Nusantara, as the Majapahit called their archipelago, commingled with silver, silk and ceramics from China, along with gold and ivory from India and Africa — a cosmopolitan empire in a world that was becoming ever more interconnected.

The remaining structures at Trowulan are a hodgepodge of architectural features — ornamental gates and statues, small water temples and a large reservoir. There is no overarching monument like Borobudur or Angkor Wat, no evidence of the true power of the Majapahit beyond what we know from written sources. Rather, it’s largely left to the visitor to imagine what it would have been like at its peak in the 14th century, particularly during the reign of King Hayam Wuruk and his powerful prime minister, Gajah Mada. The handful of structures standing today are just a hint of the capital city that must have existed seven centuries ago.

At the heart of the Majapahit empire was the mighty Brantas — ‘a continuation of the ocean’, according to Agni Mochtar in a wonderful presentation at SOAS, available on YouTube. This river connected the fertile inland areas, their rich volcanic soil refreshed by regular eruptions of ash nourishing vast rice fields that fed the empire. There were small harbors along the route (which changed course over time as the river meandered through the volcanic plains), but the main harbor was ~30km east of Trowulan, nearer the Java Sea close to Raos Pacinan, the site where Raden Wijaya hid before his attack against the Kediri army with the Mongols. Traveling up the Brantas from the coast to Trowulan took around two days, according to the Nagarakretagama manuscript (part of the Lombok treasure captured by the Dutch in 1894), and the river was potentially navigable all the way to Malang. Like the Srivijaya, a powerful thalassocratic empire on Sumatra that ruled from a capital in present-day Palembang (of which very little archaeological evidence remains), the Majapahit empire is perhaps best navigated — and understood — from an aquatic vantage point. Barring that, though, there is the modern railway snaking its way along a similar route.

After a day spent exploring Trowulan, I hopped on the train back to Surabaya for the night. My visit to the Majapahit capital was just a small part of my journey across Java. During this first part of the trip I hoped to get a sense of the places that had birthed this powerful kingdom and, via some sort of geographically-inspired conjuring of imagination, perhaps gain some insights into the characters involved. In order to do that, the next morning I boarded another train in Surabaya bound for the city of Malang.