On our recent trip to Singapore, Holly and I had the opportunity to indulge ourselves with a rare culinary splurge. While we are pretty serious cooks at home, as anyone who follows me on Twitter or Instagram has probably gathered from our many dinner posts, we don’t get a chance to eat at world-renowned dining establishments that often here on Lombok. We do have excellent restaurants, ranging from local Sasak delicacies to Korean to Chinese to Tex-Mex to European - plus tasty Indonesian and Thai delivery - but we don’t have anything that would be on the radar of the team at Michelin. Our meal at Candlenut in Singapore rectified that, even if many Peranakans might balk at a ‘haute’ version of their cuisine.

Candlenut is the first Peranakan restaurant in the world to be awarded a Michelin star. As I mentioned in my post on world cuisines last month, there is a distinct bias among western food reviewers toward lauding food they are familiar with, often leaving Asian cuisines undervalued in global rankings. That’s why - despite having some misgivings about the details of how stars are awarded, especially at establishments in the rarefied two- and three-star categories - I have been excited to see the team at Michelin embrace Southeast Asia recently, first in Singapore and Thailand, and finally last year in Malaysia.

At this point I suspect most people outside of Southeast Asia are wondering what I mean by Peranakan. The Peranakans are the descendants of Chinese traders who moved to the Malacca Strait over the past 600 years, settling in entrepôts such as Melaka, Penang and Singapore. As I discussed in my post on the history of Singapore, this strait between Sumatra and Peninsular Malaysia has been the primary maritime trade route between the Indian and Pacific Oceans for millennia. Most of the Chinese traders who settled in the Strait in the early days were men, as you might expect, and if they decided to stay they often married local Malay women, creating a vibrant culture that combines both Chinese and Malay influences. The Peranakan Museum in Singapore, which reopened on February 17 after being closed for refurbishment for the past four years, celebrates the fascinating history of the Peranakans - it’s well worth a visit.

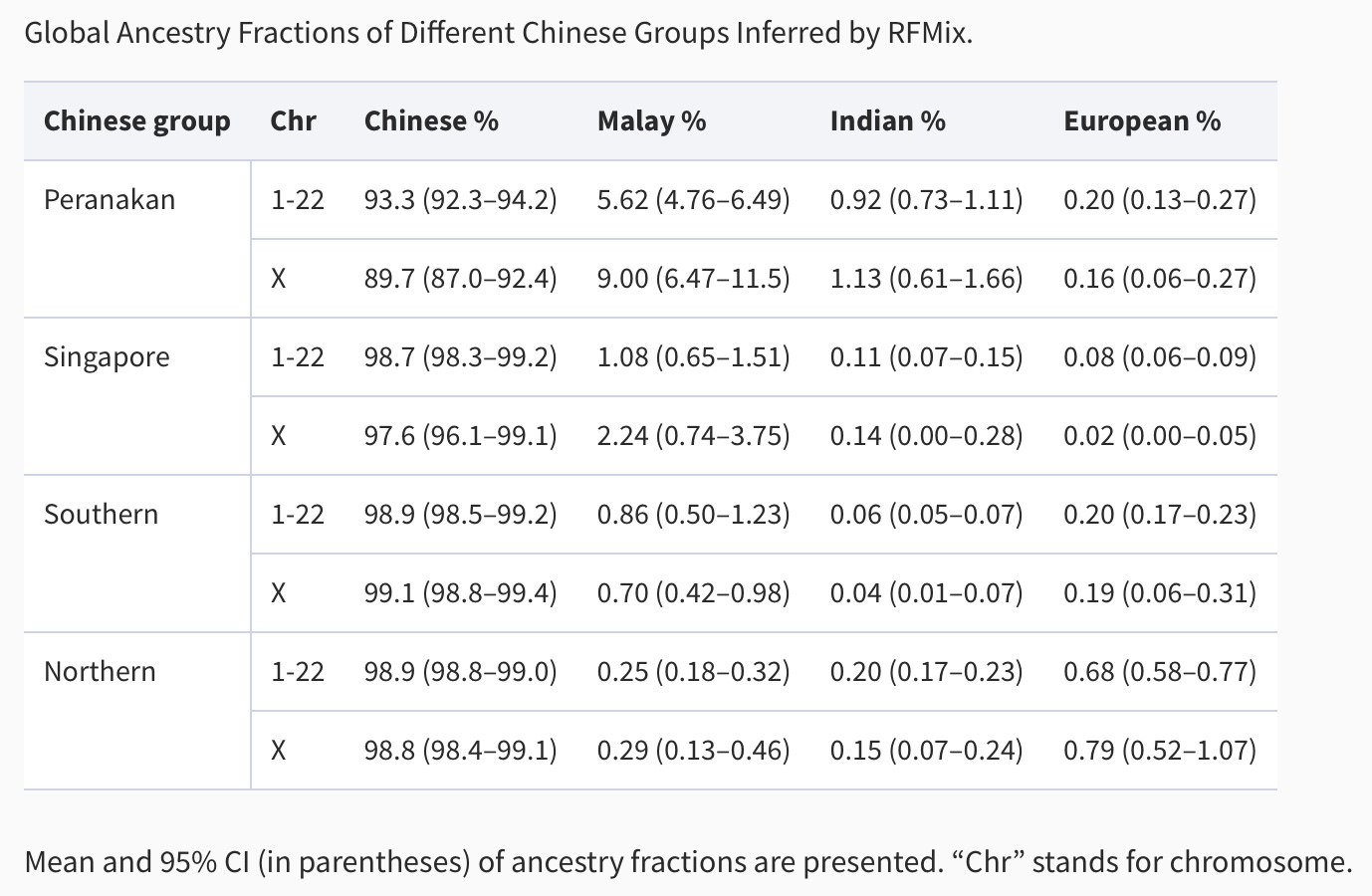

A recent study on the genetics of Singapore Peranakans has revealed the details of the biological mixing that happened in these communities over the past several hundred years. Whole genomes were sequenced from 177 Peranakans, and the data were compared to other populations around the world. The analysis reveals that the Peranakans have ~5.6% Malay ancestry across the whole genome, around 5x higher than Singapore Chinese. By looking at the X-chromosome and mitochondrial DNA (a maternally inherited piece of DNA that only reveals ancestry from your mother’s mother’s…mother’s side of the family), the study estimated that ~12% of Peranakan female ancestry derives from Malays. At the DNA level, then, the Peranakans are clearly a fusion of these two populations.

Although still predominantly Chinese genetically, and sometimes referred to as ‘Straits Chinese’, the Malay wives brought their own culture to the kitchens of the Peranakan families along with their DNA, creating a vibrant mix of Chinese and Malay dishes that are among some of the most delicious food to be found in Southeast Asia. The contributions of both Malay and Chinese ingredients & techniques to Peranakan cuisine are representative of their broader contributions to Southeast Asian food in general. Let’s dive into a recipe for one of the most iconic Peranakan dishes, Nyonya laksa (also called laksa lemak), to see what I’m talking about.

Nyonya is the Malay word for ‘woman’ or ‘wife’, and it is used in much of Malaysia to refer to the Peranakan cuisine of Melaka, though it is also used more broadly for all Peranakan food. Laksa is a noodle dish, and like all noodles in Southeast Asia, these were originally brought to the region by the Chinese. The noodles are typically cooked separately and combined in a bowl just before serving with a complex curry sauce. The sauce has an intoxicating mix of scents and flavors that reveal the many Malay contributions to the dish.

Nyonya laksa uses a coconut milk broth. Some varieties of laksa, like the one you find in Penang, are based on a sour fish & tamarind-based broth. Sarawak laksa, a specialty of Kuching in Malaysian Borneo that was dubbed ‘Breakfast of the Gods’ by Anthony Bourdain, uses a combination of tamarind and coconut milk, with star anise often added to give it a more ‘Chinese’ flavor (at least to my palate). Coconuts were first domesticated by the Austronesian ancestors of the Malays and Indonesians, and coconut milk is used in curries throughout the region, from southern Thailand through Malaysia and Indonesia. This gives the dish a creamy richness that’s absolutely delicious. Like many Malay dishes, it uses galangal, lemongrass and turmeric to provide a tangy acidity and vibrant yellow color to the broth. Belacan, or shrimp paste, is used to add umami and mild seafood notes to the broth. Finally, like most Malay food, it uses chilies - native to the Americas and originally introduced to southeast Asia by the Portuguese in the 16th century - for spiciness.

The broth ingredient that might be least familiar to those new to Malay cooking is candlenut, used to add depth of flavor and thickening. Candlenut (Aleurites moluccanus) is another species that was first domesticated by the Austronesians, probably in Maluku - the Spice Islands of eastern Indonesia - and it’s interesting because the uncooked seeds are slightly toxic. For this reason it’s only used for cooking, where the toxic compounds are inactivated through heating. The oily ground paste, similar to crushed macadamia nuts, is a critical addition to Malay curries.

Add all of these ingredients together and the result is an explosion of flavor that is undeniably Malay in origin, with a flavor profile that also connects it to other southeast Asian foods - particularly southern Thai curries. It’s not Chinese, but the noodles are clearly pulled from the Chinese diaspora. It’s a fusion dish that would be unthinkable in either culture in isolation, and it only exists because of the cultural mix found in the Strait of Malacca.

The uniqueness of Peranakan cuisine has been a touchstone for the people themselves, serving as an important way to define their culture. For a small diaspora population (there are probably fewer than 10,000 Peranakans in Singapore) living far from their paternal Chinese homeland and trying to create a cultural identity from disparate elements, food has often been a uniting element for the Peranakans. While largely Malay in style, Peranakan food has also served as a way to distinguish the fusion culture from its original cultural background. Khir Johari, author of Food of the Singapore Malays, has joked that the way to make a Malay dish Peranakan is to cook it with pork - something anathema to the predominantly Muslim Malays.

Historically, any Peranakan nyonya would be an expert in preparing food in this style for her family, but as times have changed - women have pursued careers and people have married outside of their cultural groups - many have lost the knowledge traditionally gained through long years spent apprenticing in the kitchen with their mothers and aunties. Cookbooks have been written in an attempt to preserve ancestral recipes, among the first being Mrs. Lee’s Cookbook - compiled by the mother of Singapore’s first prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, himself a Peranakan. More and more men have also learned to cook the recipes of the nyonyas, among them Malcolm Lee, founder and executive chef of Candlenut restaurant in Singapore.

What make’s Lee’s Candlenut so wonderful as an introduction to Peranakan cuisine for those not already acquainted with it is that he is a talented chef who is passionate about passing on his accumulated knowledge of Peranakan food culture using the best ingredients possible, showcased in a diverse collection of dishes. The tasting menu is a great place to start, and invites Google searches as the small plates are delivered to the table, even with the careful explanations from the wait staff. I’ve posted a photo of the menu from the night we visited below - feel free to scour the internet and start your own exploration of this fascinating O.G. Asian fusion cuisine, and check out the recommendations below if you want to learn more.

Adiditonal reading

The Food of Singapore Malays A magisterial, award-winning, lavishly illustrated exploration of Malay cuisine and culture from a Singapore perspective, including a section on Peranakan food.

Can Cultural Identity Be Defined by Food? A beautifully written and photographed introduction to Singapore’s Peranakan food culture published in the New York Times last November.

Laksa is absolutely one of my favourites here in Indonesia! My Chinese-Indonesian wife often gets it for lunch.

Brings back great memories.