The dingo is probably as iconic a symbol of Australia as the kangaroo and koala. These wild dogs excel at living in a wide variety of environments throughout the country, and it’s hard to imagine the Australian landscape without them. The only problem is, unlike the marsupial kangaroos and koalas, the placental dingo came from elsewhere — there are no placental mammals (apart from a few species of bats and rodents introduced from nearby Indonesia in the past 15 million years) evolutionarily native to Australia. Because the continent of Oceania was separated from the main line of mammalian evolution for so long — its last continental partner was Antarctica — Australian mammals followed the marsupial and monotreme evolutionary paths. Whenever we see a placental species on Australia, whether human, bat or dingo, we have to ask where it came from and when it arrived.

And this is where the dingo throws us a ‘curly one’, as Australians like to say of a difficult problem. Unlike bats, which can disperse over water fairly easily by flying, and rodents, which can stow away on floating mats of vegetation washed into the ocean during storms, larger animals like dingoes are more limited in their maritime migratory abilities. Consistent with this, the dingo doesn’t show up in the archaeological record in Australia until quite recently. The curly part, though, is when they seem to have arrived. Unlike mammalian species such as domestic cats, sheep, cattle and pigs, all of which were introduced in the past 250 years by European colonial settlers, the dingo has been in Australia for at least 5,000 years. It’s the precise timing of this introduction that’s so difficult to explain without a rethink of Southeast Asian prehistory.

Until recently, the advent of long-distance maritime interaction in the region was thought to have dated from the expansion of Austronesian sailors from their homeland in Taiwan beginning around 4,000 years ago. Driven by population growth enabled by the adoption of rice agriculture, these early Austronesians moved southward into the Philippines around that time. They aren’t thought to have started settling in present-day Indonesia until around 3,500 years ago, when their characteristic pottery and evidence of rice agriculture show up in the archaeological record at sites such as Gua Sireh and Liang Abu in Borneo. The accepted explanation for the introduction of dingoes in Australia has been — for decades — that the Austronesians brought them (ultimately from China, where dingo DNA traces back to) and introduced them on their early voyages south of Wallacea.

An emerging synthesis of genetics and archaeology now places the dingo in Australia between 5,000 and 12,000 years ago (kya), well before the Austronesians reached Wallacea, leaving this explanation abruptly adrift. But if not Austronesian sailors, with their celebrated long-distance navigational skills, who could have introduced dingoes to Australia from Asia so early on? The surprising answer comes from recently discovered archaeological and genetic evidence on the islands of Timor and Sulawesi, and a radical reinterpretation of the history of maritime navigation in the region.

Jerimalai rock shelter is located on the remote far-eastern end of the island of Timor in Wallacea. It is part of a group of caves in the region that have been studied extensively over the past 20 years by Sue O’Connor and her colleagues as part of an effort to understand the early peopling of Australia from Southeast Asia. The many fascinating discoveries include a human presence in Lene Hara cave from ~43kya, cave art dating to 29-24kya, and fascinatingly, overwhelming evidence of pelagic fishing dating from ~42kya in nearby Jerimalai rock shelter. Clearly, these people were fairly sophisticated sailors even at these early dates, not only to have reached Timor in the first place — which was never connected to the other islands nearby during periods of lower sea level during the Pleistocene — but to have routinely exploited marine resources like tuna in the deep waters off of Timor for tens of thousands of years.

The evidence for pre-Austronesian seafaring in island Southeast Asia is clear, but who were these early sailors? In my post on the arrival of early modern humans in the region I discussed the two-layer model of human settlement in the region. Recent finds, however, have shown the underlying complexity of this model. In 2015 a skeleton was unearthed at Leang Panange cave in southern Sulawesi. Dating to 7.2kya, she was named ‘Bessé’ by her discoverers, a term of endearment used by the local Bugis people for their newborn girls. She belonged to the well-documented Toalean hunter-gatherer culture of the region, which existed from ~8kya until ~1.5kya. ‘Toale’ means ‘people of the forest’ in the Bugis language, and these people lived for ~2,000 years alongside the newly-arrived Austronesians — the ancestors of the Bugis and other present-day inhabitants of Sulawesi.

In 2021, Adam Brumm and his colleagues at Griffith University in Australia published the analysis of Bessé’s genome — the oldest complete ancient genome ever sequenced from Southeast Asia. It revealed the first detailed glimpse of the pre-Austronesian inhabitants of Wallacea, which turned out to be rather surprising.

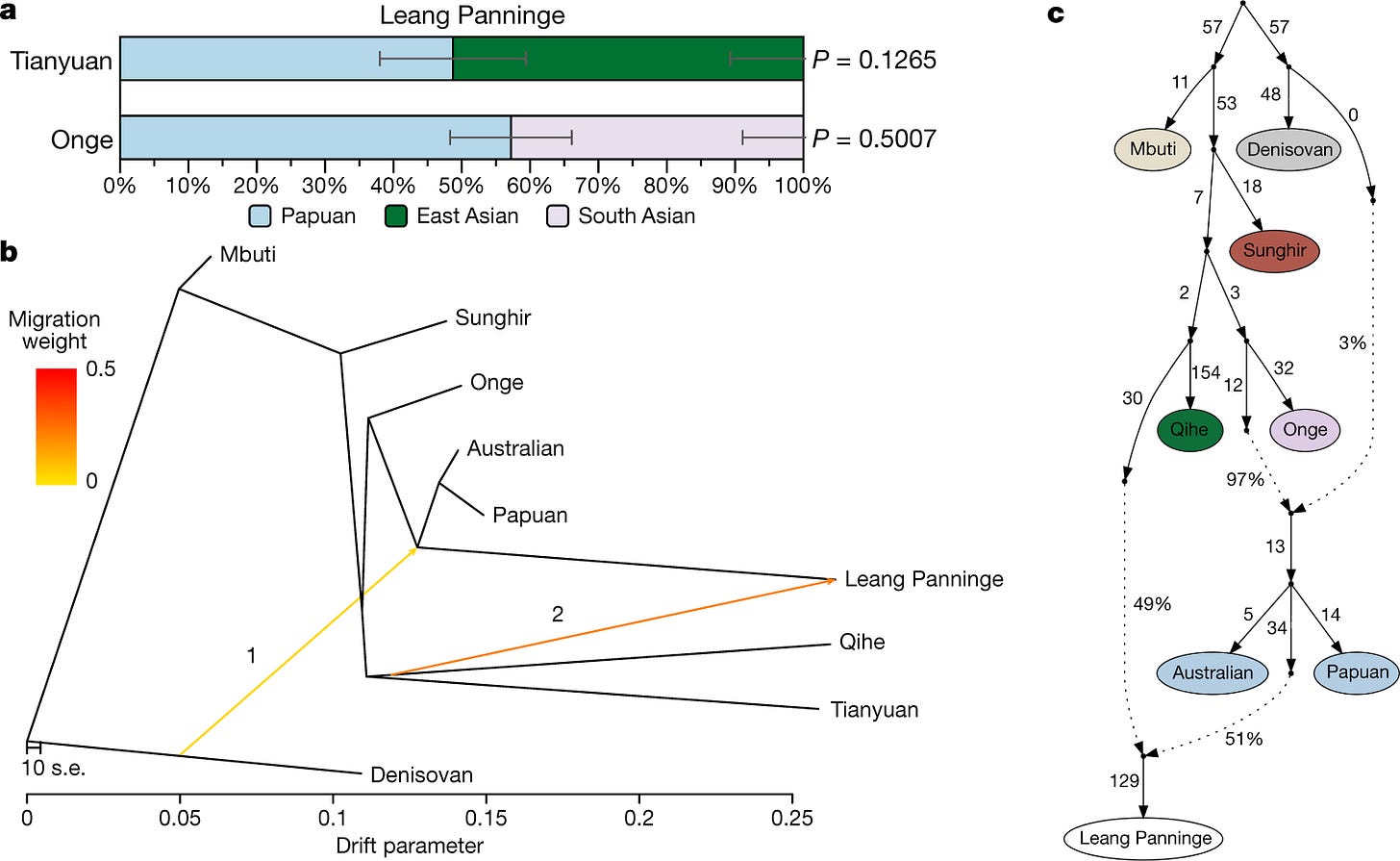

Using a methodology that modeled the admixture proportions from both ancient specimens and modern human populations, the analysis inferred that Bessé was a mix of approximately half Australian Aboriginal/Papuan and half East Asian. A priori, this is what you might expect from a modern inhabitant of Wallacea, after the Austronesian migrations of the past 3,500 years. To find such a high level of Asian ancestry at this early date though, thousands of years before the Austronesians appear in the archaeological record, is surprising. The closest match in the ancient genomes sequenced up to that point was to an early Neolithic individual excavated at Qihe cave in Fujian province, southern China, dating to ~8400 years ago. The Qihe individual is closely related genetically to the later Austronesians, who migrated to their homeland in ancient Taiwan from mainland southern China between ~10kya and ~6kya. Qihe appears to provide a genetic glimpse of these early Austronesians around the time of their genesis.

The analysis of Bessé’s genome suggests that there was contact between Wallacea and southeastern China by at least 8,000 years ago. As shocking as it might seem for Paleolithic cultures to have widespread maritime networks — previously thought to be the purview of Neolithic and later peoples — it is supported by a recent study of stone tools carried out by Sue O’Connor and her colleagues. In a recently published study of obsidian (a valuable volcanic stone used for making sharp tools) and polished adzes, she and her team found clear evidence for significant late Pleistocene trade networks of these commodities in both the Philippines and southern Wallacea, perhaps even connecting the two regions, dating to ~12kya. Her hypothesis is that rising sea levels at the end of the ice age served as a powerful impetus for cultures with preexisting maritime technology — such as those living in Wallacea — to expand the geographic range of their trading networks. It’s interesting to speculate that this might have led to early contact between the peoples of southern China and the Philippines, and perhaps even populations living in further away in Borneo and Sulawesi — including the ancestors of the Toaleans. Could these pre-Austronesian sailors have journeyed beyond Taiwan, into the Ryukyu Islands or even the main Japanese islands of Kyushu or Honshu? Intriguingly, the pre-Neolithic Jomon population of Japan shows genetic similarities to aboriginal Taiwanese and the Igarot population of the Philippines — both thought to be remnants of early Austronesian populations, though the genetic interaction is estimated to predate the Austronesians and is most likely part of a Pleistocene coastal migration.

The answers to these questions about the extent of late Pleistocene Wallacean voyaging and interaction can only be resolved with additional data, including ancient DNA analyses of older human remains from the region. Intriguingly, Brumm and his team have recently discovered the remains of a Late Pleistocene modern human on Sulawesi — hopefully the DNA of this individual will still be intact and shed light on the pre-Toalean inhabitants of Wallacea. The earliest stone tools on Sulawesi date to between 100-200kya, which suggests that hominins have been present there for a long time. Do these early tools belong to the Denisovans, as some have suggested, or are they evidence of yet another hominin in the region — perhaps related to the ‘Hobbits’ of Flores, who are thought by many researchers to have arrived on Flores from Sulawesi during the past 200,000 years?

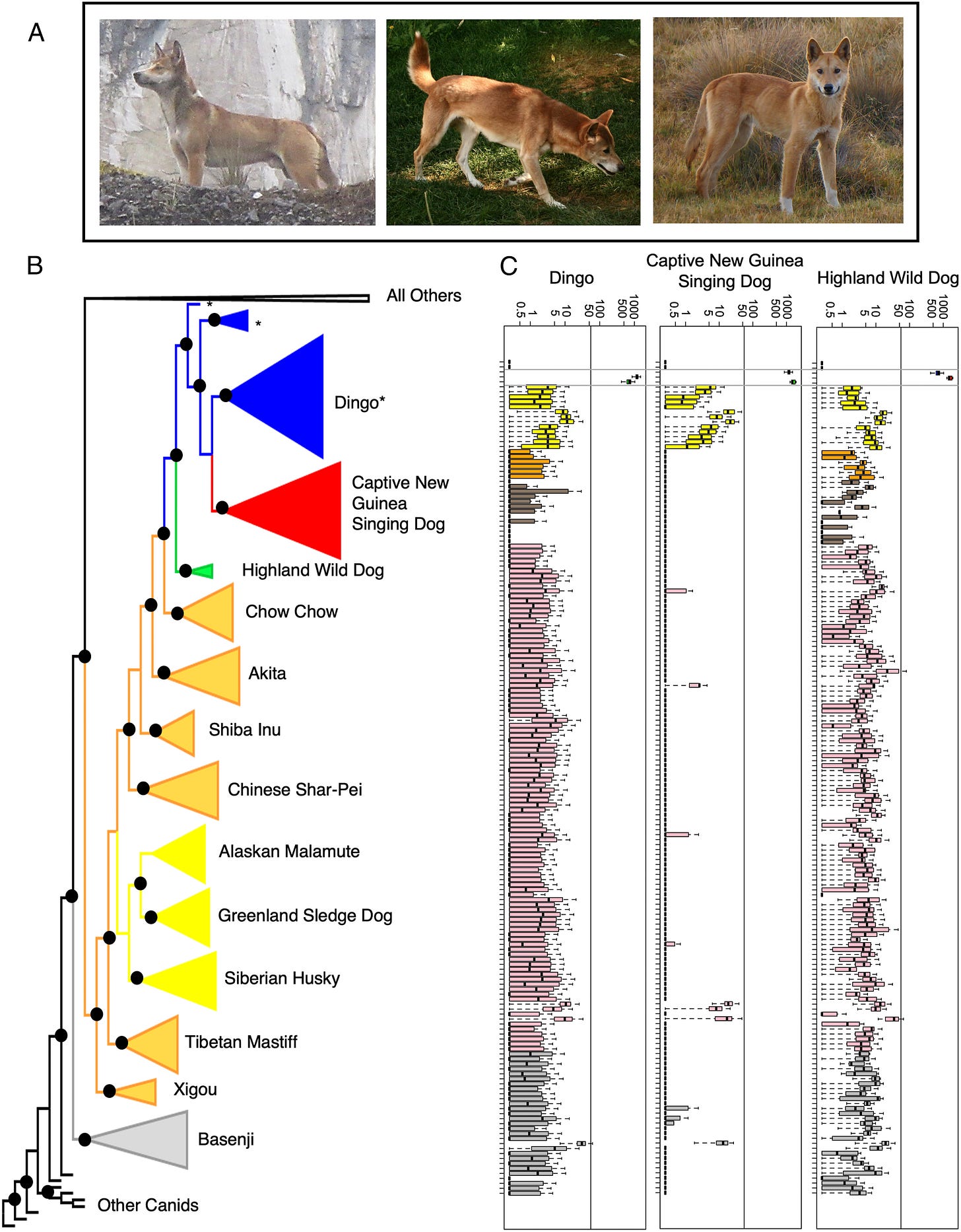

Finally, we return to the question of how the dingo got to Australia. Synthesizing the data from genetics and archaeology across this vast region of islands, it seems likely that late Pleistocene seafarers brought domesticated dogs from a pre-Neolithic population in China. Why pre-Neolithic? Because of the calculated genetic divergence between the dingo and East Asian dogs, and the fact that the dingo doesn’t show the duplications of amylase genes typically seen in dogs domesticated in farming populations as an adaptation to the increased starch in their diet from grains like rice. These hunter-gatherer canine companions likely island-hopped via the Philippines down into Borneo over many generations — the same route taken by the later Austronesians. Once in Wallacea it would have been fairly easy for these accomplished seafarers and their dogs to reach both Australia and New Guinea, where the New Guinea singing dog is a close cousin of the dingo. Quite a journey for ‘man’s best friend’ — domesticated dogs crossing the ocean thousands of kilometers from an ancient homeland in China to the continent of Oceania with these intrepid early Wallacean sailors, then returning to the wild once they arrived in their new homes.

Loved some Wildlife Zoology reads calms me perfectly.. https://kallolpoetry.substack.com/p/he-consumed-me-everyday-so-i-devoured