I stepped off the plane at Ashgabat airport and entered the passport control queue, uncertain about whether my e-visa would be valid. It was just before midnight on September 15, 2008, and I had made the short hop across the Caspian Sea from Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan. It was a flight I hadn’t intended to take, and had been hastily arranged based on bad weather and good advice.

Let’s step back for a bit of context. In the course of my work on the genetic history of humanity I’ve traveled to over 100 countries, from Peru to Namibia to Papua New Guinea. My first studies, though, were focused on Central Asia. In the summer of 1996, while a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford, I organized a five-week expedition to Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan. Among other things, the samples we collected that summer would lead to the discovery of the Y-chromosome marker M17 - the first stable genetic marker for the widespread male lineage we now refer to as R1a, spread by early Indo-European steppe nomads during the Bronze Age.

One thing was crystal clear from the early results those samples yielded: we needed DNA samples from a far wider swath of Eurasia to make sense of the patterns we were seeing. So, in 1998 I led another expedition to the region - but with a twist. Since we would need rugged transportation to get to many of the remote locations we planned to visit, and would be carrying quite a lot of equipment and reagents with us, an overland trip made sense. Because the journey we planned would take in some of the least-known parts of the world at that time, the nascent explorer in me thought it would a fantastic opportunity to undertake an epic, multi-month overland expedition, reported live on a website (which I coded myelf in tedious, text-editor HTML) with team updates from the road. Fundraising throughout 1997, greatly aided by my friend and London-based photographer Mark Read (who had accompanied me to Central Asia in 1996), we managed to cobble together enough support to undertake the expedition - including a brand-new Land Rover Discovery given to us by the company as sponsorship, and a featured section on the newly-launched BBC News website that spring. In late April 1998 we set out from London, aiming to drive to the Altai Mountains in southern Siberia via Turkey, the Caucasus, Iran and the ‘stans of Central Asia.

It was a very different era. Travel was much easier during that brief decadal window than it has ever been in my lifetime. The Cold War had ended seven years before and post-9/11 travel security restrictions were still three years away. Far fewer people were traveling at all - Chinese tourists were merely a footnote rather than a major force. No one even considered the possibility of a coronavirus pandemic erupting globally and bringing international mobility to a halt. Perhaps most importantly for us, the former Soviet Union was open to the West in a way it has never been before or since - we were lucky to be able to drive through all of the recently independent states on our own, welcomed with open arms. We had even been granted permission to collect DNA samples in Iran and Turkmenistan, which would be off-limits in today’s much more bitterly-divided world.1

I had come back in 2008 to see the changes that had taken place over the previous, rather eventful, decade. My original plan had been to retrace the route almost exactly, but geopolitics and Caspian Sea weather put an end to that. Russia invaded South Ossetia, an ethnically-distinct breakaway region in north-central Georgia, in August 2008, and despite a hastily arranged ceasefire the country was too unstable to risk a visit in early September. That meant flying directly from my starting point of Istanbul to Baku, with the intention of taking a ferry across the Caspian to Turkmenbashi, on the Caspian coast of Turkmenistan, as I had done in 1998 after a border fiasco kept me trapped in the country while the rest of our team conducted the sampling in Iran.

Unfortunately the weather in 2008 intervened and kept me in Baku beyond my planned departure. The winds whipping across the Caspian made a crossing too dangerous, especially in the decrepit Soviet-era ferries that hadn’t been updated since I took one ten years before. I also heard from several sources that there were often significant delays in docking on the Turkmen side - up to two weeks, on a sweltering piece of rusty metal not meant for passengers (you had to pay a crew member to sleep in his cabin, even when I made my crossing). I decided that time, comfort and safety considerations trumped authenticity, and booked a flight to Ashgabat. In the intervening ten years it had also become a requirement to book an entire itinerary with a travel agency, accompanied by a guide and driver, so it was going to be a very different experience even after I arrived in Turkmenistan.

After making it through customs and sleeping off the flight, I woke up the morning of September 16 and wandered down to the breakfast area of my hotel. The television was tuned to a Russian news station, and the announcer was talking about the collapse of Lehman Brothers. My Russian was a bit rusty from lack of use, so I only understood some of what he was saying. It seemed so remote, though, that I didn’t really think much of it from my vantage point in Ashagabat. I basically thought ‘OK, an American investment bank has gone under - surely that’s an isolated case of corporate mismanagement?’

My guide and I spent the next two days touring around Ashgabat, revisiting some of the same places I remembered from a decade before, and taking in the recent insanity bequeathed to the city by the late president Saparmurat Niyazov. Self-styled as Turkmenbashi (‘father of all Turkmen’) just before I visited in 1998, he really began to go off the rails soon afterward. In the years before his death in 2006 he renamed major cities and months of the year after himself and members of his family, replaced the Cyrillic alphabet with a modified Roman-derived one that he helped to create, abolished the Academy of Sciences we had collaborated with in our sampling there, outlawed western classical music and ballet, and wrote an appallingly bad mishmash of a book based loosely on Turkmen mythology interspersed with his own life advice that was made a required text for schools and driving tests. He even built a gold statue of himself holding his arms up to the heavens that rotated throughout the day so that it always faced the sun. Completely loopy.

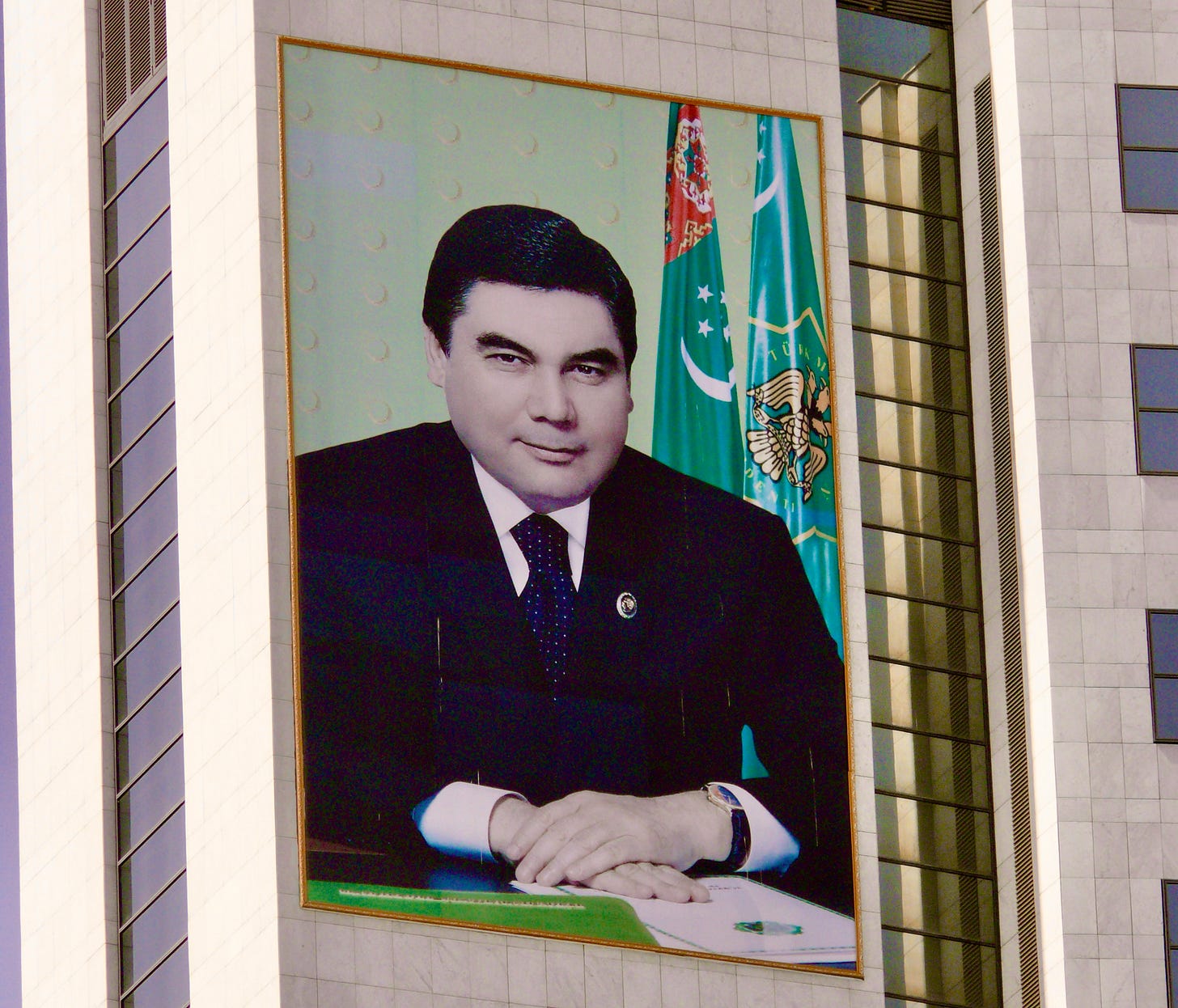

By the time I arrived in September 2008 he had been succeeded by Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov, a previously obscure dentist who had been made the Minister of Health in the late 90s, then Vice-President in 2001. He was rumored to be Niyazov’s illegitimate son, though this has never been confirmed. Sure enough, though, when I was in Turkmenistan in 2008 gigantic billboards of his stern visage were plastered over every major building in the city, in the same style begun by his purported father in the mid-90s.

The next few days we rode through the desert to the miserable enclave of Mary, a decaying ex-Soviet settlement that sweltered under temperatures exceeding 50°C in the summer. From our base there we visited the ancient ruins of Merv and Gonur Depe. The latter was the capital of the Bronze Age Bactria-Margiana culture, which built a thriving urban enclave in the harsh desert on a side tributary of the Murghab River in the mid-3rd millennium BCE. Gonur Depe was probably the earliest major center of interaction with the Indo-Aryan steppe nomads to the north before they expanded toward the urban settlements of the Indus Valley to the south, as part of their migration into the Indian subcontinent in the 2nd millennium BCE.

At my hotel in Mary the news continued to cover the teetering banking system in the US, with fears of bank runs and complete economic collapse as investors withdrew record sums from money market funds. It seemed so distant from my vantage point in a decaying backwater town in the middle of the Karakum Desert, with thoughts about the ebb and flow of empires from my archaeological explorations making it seem even more surreal. “No empire lasts forever,” I remember saying at dinner one night - something that resonated with those who remembered the Soviet era and the debilitating chaos of its breakup in the 1990s.

After Mary I made my way to the Uzbek border on the Amu Darya river, crossing over to the Uzbek side on foot among a group of Japanese tourists. There I met up with an old friend from the Uzbek Institute of Immunology in Tashkent who had collaborated with us on the DNA sampling in 1996 and 1998. I had managed to obtain grant funding to bring her to the UK to work in my small research group at Oxford (she’s now on the faculty at the University of Leeds), and she had flown back to Uzbekistan to accompany me to some of the same locations we worked in on those expeditions. Uzbekistan is probably the best-known country in Central Asia, so there’s no need to recount visits to its famous Silk Road cities of Bukhara and Samarkand, or the Aral Sea (which had shrunk considerably since my first visit in 1996). I continued on to Kyrgzstan and Kazakhstan over the next two weeks, taking in the glorious State Historical Museum in Bishkek and enjoying the gently-decaying Russian colonial town of Karakol (former Przhevalsk, named after the great Tsarist explorer who had died there in 1888). Back in the US, Washington Mutual bank had declared bankruptcy and the stock market had crashed, with the Dow falling 7% on September 29th. It was clear that something was deeply wrong, but it still seemed so far away, especially as the first snows started to fall in Kyrgyzstan’s Tien Shan mountains.

In early October I finally found myself in the Kazakh capital Astana, meeting with the Prime Minister, Karim Massimov.2 Dr. Massimov had requested a face-to-face meeting with me to discuss our planned Genographic Project sampling in Kazakhstan. I was worried that he wanted to personally give me a dressing-down for proposing such work, perhaps accusing me of attempted biopiracy and deporting me on the next flight to Europe. Needless to say, I was a bit nervous when I walked into his office. He introduced himself in fluent English (one of five languages he spoke, including Chinese and Arabic), and told me a bit about his time as a banker in Hong Kong. After about 15 minutes he stopped talking and looked me directly in the eye. “I suppose you’re wondering why I asked for this meeting?” I gulped and replied that yes, it was an honor to receive the request, and I was indeed curious. He then pulled out his Genographic DNA test results and asked me to interpret them personally. It turns out that he had been a fan of the project since we had launched in 2005, and was simply curious - as an ethnic Uyghur - to learn more about what they meant. I sighed in relief and smiled, and we spent half an hour discussing ancient migration patterns in Central Asia. When I left he told me that he would ask his staff to prepare an order immediately providing full government support for our proposed work in the country.

My flight back to the US was uneventful, but the country I was returning to had changed enormously in my six-week absence. It turned out that all of those surreal news snippets I had heard were in fact the horsemen of a US economic apocalypse. I was still trying to catch up on what it all meant - and recovering from a rough case of jetlag - when I decided to call a good friend who was a successful banker. “Frank, what the hell happened?” I asked, genuinely curious about his take. He cleared his throat and said tersely, “Some guys did some things they shouldn’t have, and it’s going to cost us all a lot of money.” That it certainly did.

The United States entered the 21st century with a budget surplus, the largesse of responsible fiscal management and a ‘peace dividend’ in the post-Cold War years of the 1990s. The Neoconservative-driven military adventures in Iraq and Afghanistan have since destroyed that 1990s largesse, abetted by an era of politically-driven cheap money in the form of historically low interest rates and poor regulation that led to the crisis and the ensuing bailouts of the global financial system in 2008-2009. The Covid-19 pandemic only served to accentuate this, leading to the largest US government debt levels since the Second World War. As interest rates have increased rapidly from historically low levels since early 2022 in order to combat high inflation, banks have seen their bond assets plunge in value, leading to the demise of Silicon Valley Bank, Credit Suisse, and others. It remains to be seen where this will lead long-term, but having witnessed the surreal events of 2008 playing out from the other side of the world, today’s crisis certainly sounds like a familiar tune when heard from afar here in Indonesia, even if the song itself is different. Time shall tell where the current chain of events ultimately leads, but as many said during the last time this tune played 15 years ago: buckle up.

I’m finishing up a book on the 1998 trip and our scientific findings, which needless to say are a bit too extensive to summarize in a short blog post…stay tuned.

Unfortunately Massimov was dismissed from the government and arrested during the Kazakh protests in January 2022. He remains under arrest for what appear to be politically-motivated, unsubstantiated offenses.

I will be back over your way before too long I am sure - armed with my stories

Enjoyed this article. Looking forward to reading your book when it’s published.