The Spice Islands

My journey across Wallacea ends in the fabled Spice Islands of North Maluku

In mid-October I boarded a plane in Ternate bound for Lombok, via the cities of Makassar and Surabaya. My journey across Wallacea — from its southwesternmost point on Lombok, to its northeasternmost island, Morotai — was complete. After more than five months on the road, I was finally headed home.

In the course of my journey I’ve seen many things, but it was perhaps fitting for it to end in the Spice Islands, destination for traders, explorers and colonizers for over two millennia. I’ll be unpacking the major stops en route in a series of posts over the next few months, from the submerged medieval iron mines of Lake Matano to the mysterious megaliths of the Bada Valley. For now, though, let’s talk about spices.

The Spice Islands (Kepulauan Rempeh-Rempeh in Indonesian) are named for two species of tree that have been pivotal in world history: cloves (Syzygium aromaticum) and nutmeg (Myristica fragrans). Cloves are endemic to the small islands of Ternate, Tidore, Moti, Makian and Bacan off the west coast of Halmahera in North Maluku, while nutmeg — which I’ll explore in a future post — is endemic to the Banda Islands in Central Maluku. Although they are grown in many other places today (Madagascar, Zanzibar and Brazil are major exporters of cloves, and India and Sri Lanka of nutmeg), until a few centuries ago they could only be found on a small number of islands in Maluku.

Why here, in this remote location, rather than in the teeming, species-rich jungles of mainland Southeast Asia, Borneo or New Guinea? In short, Wallacea’s unique biogeography strikes again.

Cloves are fairly typical members of the plant family Myrtaceae, which also includes the distantly-related eucalyptus. The Myrtaceae are a widespread family of trees with evergreen leaves containing essential oil-producing glands, the flowers of which typically have a large number of stamens that create a brush-like appearance. Anyone who has been close to a grove of eucalyptus can attest to the unique odor produced by the essential oil in the leaves.

The Myrtaceae genus Syzygium, which includes the clove, is one of the most diverse in the Old World tropics, with more than 1,100 species distributed from Africa to Asia and Australia. This genus seems to have originated in Sahul (the ancient landmass encompassing Australia and New Guinea) and spread westward from there over the past ~30 million years to the other parts of the Old World. As part of this westward movement out of Sahul it has diverged into a huge number of species on the isolated islands of Wallacea. While a handful of species produce edible fruit such as rose apples and have been cultivated as food in Southeast Asia and Polynesia for millennia, most are not especially important economically. The clove, on the other hand, most definitely is. Clove flower buds contain high concentrations of eugenol, an aromatic chemical compound also found in cinnamon, nutmeg and basil. This aroma and the associated flavor — along with its anesthetic properties (toothache, anyone?) — have made cloves a sought-after commodity for at least two millennia.

Cloves were exported to China as early as the Han Dynasty (202 BCE-220 CE) where emperors required visitors to the court to chew on cloves in order to freshen their breath. The name for clove in Malay, Javanese and Balinese, cengkeh, derives from the ancient Chinese word for them,丁香 ding xiang (‘perfumed nail’, because of their shape) revealing the powerful impact of the trade with China on the Indonesian spice trade.

Cloves are an important component of Indian cuisine, appearing in a wide variety of curries, suggesting an ancient connection to the Spice Islands. Cloves were found at Terqa, in present-day Syria, dating to 1720 BCE, although this was a one-off find. The next-oldest archaeological evidence dates to 900-1100 CE in Sri Lanka, showing that the trade between South Asia and Maluku was well-established by the latter part of the first millennium CE, and probably much earlier.

The earliest long-distance East Asian trade in spices was probably carried out by the Yue people of southern China, who came under the control of the Chinese Qin Dynasty in the third century BCE. The Yue were described by ancient Han Chinese sources as powerful collection of tribes speaking a non-Chinese language (likely belonging to the Tai or Austroasiatic language family) with their capital in present-day Guangzhou. The Yue were famed for their seafaring ability: for instance, an early Han-era shipyard excavated in Guangzhou in 1975 by Chinese archaeologist Mai Yinghao was capable of building 30m vessels holding 60 tonnes of cargo.

It’s likely that the late-first millennium BCE spread of Dong Son bronze drums from their homeland in northern Vietnam throughout island Southeast Asia was carried out, at least in part, by Yue sailors. I’ll write more on these iconic symbols of early Southeast Asian bronze-making technology in a future post.

The Chinese harnessed the Yue maritime expertise to expand their access to the spice trading markets of the South China Sea, including Funan — an early first millennium CE state in the Mekong Delta that would later evolve into the Khmer Empire. It was from Funan that the Han Chinese likely obtained their cloves, and although they seem to have known that they were grown somewhere to the east in the Indonesian archipelago, the islands of North Maluku remained terra incognita.

How did the cloves chewed by visitors to the Han court make it from the remote islands of North Maluku to Funan? Early Indonesian trade routes to the east were probably already established in the latter centuries of the first millennium BCE, though perhaps in a relatively disorganized way. It’s likely that external demand from China, and later India and Sri Lanka, drove the expansion of the clove trade in the Indonesian archipelago. By the early centuries of the first millennium CE, spices from Maluku were a well-established commodity in both the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean. Some of these cloves even made it as far as Rome, one of the first food products to be traded from eastern Eurasia to the empires of the West (black pepper is native to southern India, so its journey was far shorter).

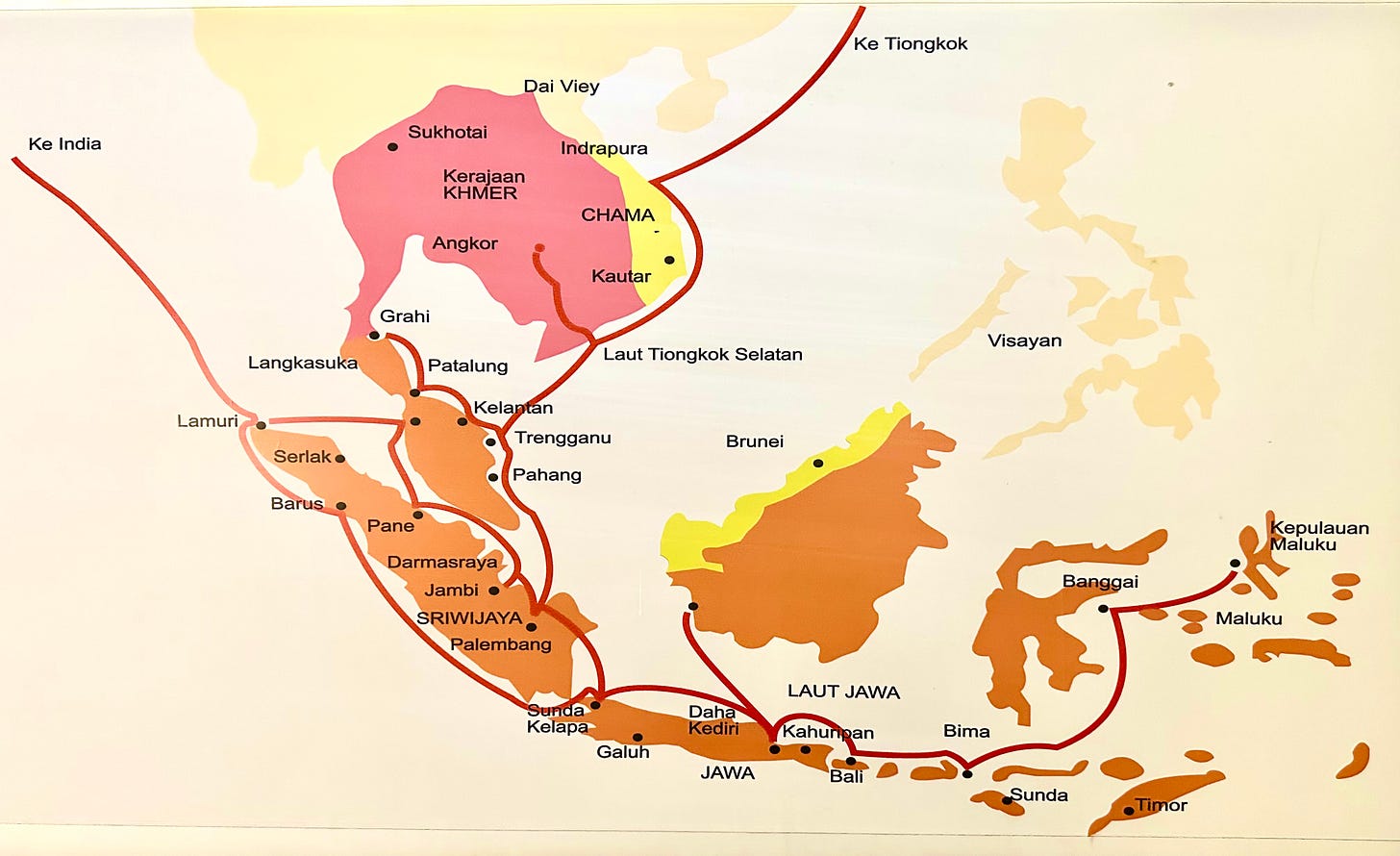

While some Austronesian vessels would make it as far as the island of Madagascar, which was initially settled by migrants from southeastern Borneo in the middle of the first millennium CE, likely using ships similar to those portrayed in the carved reliefs at the Buddhist temple of Borobudur on Java, most trading was within defined geographical centers of influence. By the end of the first millennium CE a stable pattern had emerged, with Indonesian sailors bringing spices (and other items) from the islands of eastern Indonesia to trading entrepôts in present-day Sumatra, Peninsular Malaysia, Vietnam and Cambodia, then Chinese vessels taking them onward from there to China and Indian vessels transporting them to southern India and Sri Lanka. Finally, Arab traders with their iconic dhows (which were influenced by the design of early Austronesian vessels) carried these spices westward to the markets of the Middle East, from where they made their way into the Mediterranean. This transcontinental trade network, dubbed the Maritime Silk Road, would remain (relatively) peacefully in place until the violent arrival of the Portuguese in the early 16th century — and later the Dutch in the 17th century — armed with inferior trade goods but superior weaponry. That’s for the future post about nutmeg, though.

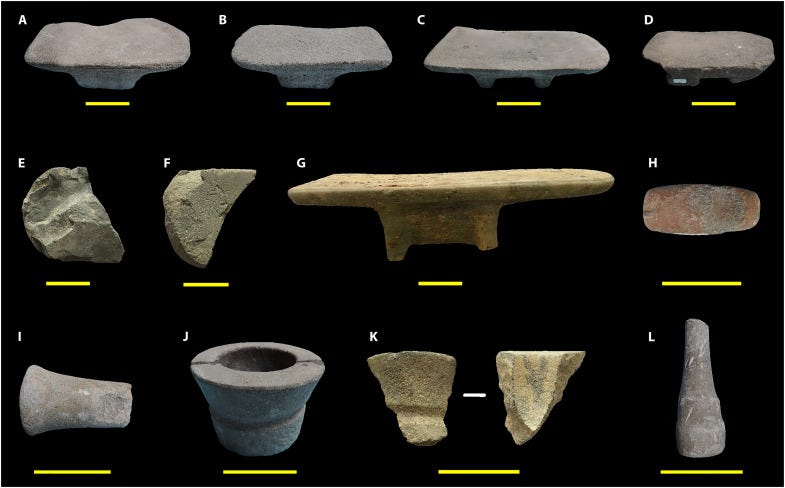

The arrival of large-scale trade networks linking Indian and Chinese civilizations in Southeast Asia in the early first millennium CE, coupled with endemic ingredients like cloves, nutmeg, lemongrass, ginger and galangal, combined to create the delicious fusion cuisines of the region we know today. A glimpse of the early culinary history of Southeast Asia was recently revealed by the analysis of 1,800-year-old grinding stones at Oc Eo in southern Vietnam, a region that would have been part of ancient Funan. The stones themselves appear to be of Indian origin, stylistically identical to those used in the subcontinent around the same time, but with no antecedents in Southeast Asia. The inference is that Indian traders, who began to make contact with ancient Funan during the early centuries CE, brought their cooking technology and ancient penchant for stews made from a combination of ground spices — which we refer to as curry today — and incorporated local ingredients into their preparation at Oc Eo.

Noel Hidalgo Tan, the curator of Southeast Asian Archaeology (well worth subscribing if you enjoy my posts on Southeast Asian history and archaeology), has recreated the type of curry that was likely made at Oc Eo nearly 2,000 years ago in this excellent post — a nice reminder that the spice trade we’ve examined briefly here ultimately comes down to enjoying delicious food created from the melding of ancient ingredients found along the Maritime Silk Road.

Thanks for the fascinating article: we just came back from Portugal and visited their Maritime Museum in Lisbon, where they proudly exhibit their great explorations during the 15th century and how they ascended to become the first global empire (conveniently left out the brutal atrocities they left behind to achieve "favorable" trading terms with their local "partners").

Another good article that sheds a different light on places I have visited previously as a tourist and done touristy or work things - Zanzibar, Madagascar and Wallacea - and been totally unaware of the history of the places. 👍🏻