Blowing up in Sumbawa

The FJ40 channels the spirit of Tambora en route to Flores

Holly and I pulled out of our driveway in Senggigi full of confidence after making it over the hurdle of packing up the FJ40. A torrential downpour the night before had flooded villages and homes on the western side of Lombok, but thankfully it left us relatively unscathed apart from an inconvenient loss of electricity — though this did mean packing while sweating profusely in the steamy final gasp of Indonesia’s rainy season. We were finally off, and the clouds slowly receded behind us as we cruised eastward across the island, making the seasonal break more palpable. Pulling onto the ferry at Pelabuhan Kayangan on Lombok’s northeastern coast, it seemed like we were finally escaping psychologically from the pandemic lockdowns and damp La Niña weather of the past three years. Cruising away from the harbor in brilliantly sunny weather, the ship set a course eastward toward Sumbawa where our Indonesian lives had started three years before.

The last time we were on this ferry route in April 2020 we were headed in the opposite direction, arriving in Lombok for the first time from our sojourn on Moyo Island off the coast of northern Sumbawa. I won’t go into the details here because I’ve covered them in previous posts, but Lombok has become our home over the previous three years. Making the crossing again after so long felt a bit like traveling back in time to those crazy early days of the pandemic.

Unfortunately, as we pulled onto the ferry the engine temperature had climbed into the danger zone. I attributed this to the long drive to the port followed by idling in the hot sun waiting to board, and quickly opened the hood to allow the engine to cool once were were parked onboard. We headed upstairs with some leftovers for lunch (a tasty batch of mapo tofu for me, my last Sichuan food for quite a while), watching Lombok and the enormous slopes of Mount Rinjani recede into the distance behind us, then gradually shifting our gaze toward the bow to see Sumabwa looming ever larger on the horizon.

Pulling off the ferry a couple of hours later, we were hopeful that the engine had rested enough to make it to our hotel, located a couple of hours’ drive away on a narrow channel facing Moyo Island. Our hopes were rapidly dashed when the temperature gauge climbed into the danger zone again. We steered the jeep onto the side of the road in front of a small family compound just to the east of the port, steam blowing out from under the hood with an angry whine. Our journey was done for the day.

The family that lived in the compound immediately ran out to see what was going on, equally curious and concerned. We opened the hood, and the husband — who assured me that he was a mechanic and knew what he was doing — used a long stick to release the radiator cap. The coolant spewed out in a burst of steam and boiling water like a volcanic eruption. More on that in a bit. The sun was starting to go down, and the lovely family helped us find a guesthouse for the night and call a driver to pick us up — Indonesian kindness shining through when you most need it.

The next day, with the help of two local mechanics, we managed to repair both the blown-out radiator hose that led to the volcanic coolant explosion, as well as the ultimate cause of the overheating engine. The upshot is that my mechanic on Lombok had adjusted the valve clearance on the engine too tightly, and as a result the engine had been running too hot since we left Senggigi. It’s amazing that it had survived the heat and pressure, to be honest, but the venerable 3.9L inline-six engine on the FJ40 is pretty bombproof — a major reason I wanted to take one on the expedition. The valve insight came from the second mechanic we found in the small town of Labuhan Alas in northern Sumbawa, who owned two old FJ40s of his own and immediately spotted the problem using a butter knife to measure the clearance. Everyone is a mechanic to a certain extent, I suppose — with plenty of opinions, like social media — but true experts are rare. We felt very lucky to find someone like Iwan in such a small town, and paid him well for his insight and effort before heading onward to our hotel, a day late but certainly better informed about FJ40 engines than we had been when we left Lombok.

We were staying at the Samawa Seaside Cottages, about half an hour north of Sumbawa Besar, the regional capital. A former plantation with a collection of standalone one- and two-bedroom wooden cottages scattered across many hectares of beautifully maintained lawns and gardens, it was the perfect place to rest after the stresses of the previous 48 hours. Located a stone’s throw from Moyo Island, it truly felt like we had come full circle.

On our first morning there we spied Mount Tambora peeking above the low coastal clouds, looking deceptively more benign than it had two centuries before when it burst flamboyantly onto the world stage. I wrote about Tambora in my 2010 book Pandora’s Seed:

Mount Kinabalu, on the island of Borneo, is [the highest mountain in island Southeast Asia at] 13,435 feet. Until 1815, however, Kinabalu…rested in the metaphorical shadow of Mount Tambora, the highest point on the small island of Sumbawa, just east of the tropical paradise of Bali. Reaching an estimated height of more than 14,000 feet, Tambora's huge, symmetrical cone soared out of the Flores Sea, which separates Sumbawa from Sulawesi. Navigators had used it as a landmark for thousands of years, and it was believed by the local people to be the home of their great god.

According to local legend, the events that reduced Tambora to a fraction of its former height happened as a result of divine retribution:

The cause was said to be the wrath of God Almighty, at the deed of the King of Tambora in murdering a worthy pilgrim, spilling bis blood, rashly and thoughtlessly.

On the evening of April 5, 1815, Mount Tambora, a dormant volcano, erupted. Actually, "erupted" is an understatement; it exploded, it roared, it destroyed, it belched forth demons. The sound was heard in Yogyakarta, 450 miles away, where the sultan rallied a detachment of soldiers to see if the capital was under attack. Over the next several days the eruption continued, reaching a climax on April 10, when the sound was heard in northern Sumatra, more than 1,500 miles away from Tambora. Sir Stamford Raffles, the colonial founder of Singapore who gave his name to the famous hotel, described it in his memoir from eyewitness accounts:

In a short time, the whole mountain…appeared like a body of liquid fire, extending itself in every direction. The fire and columns of flame continued to rage with unabated fury, until the darkness caused by the quantity of falling matter obscured it at about 8 p.m.

Stones, at this time, fell very thick…some of them as large as two fists.

Ash was thrown more than twenty-five miles into the sky, producing three days of darkness on the nearby islands. Perhaps the most powerful volcanic eruption since that of Mount Toba 74,000 years before, it spewed out more than twenty-five cubic miles of ash and stone, four times as much as its more famous Indonesian cousin, Krakatoa. The island of Bali, 150 miles to the west, was covered in nearly a foot of ash, and winds spread more ash worldwide over the next few months. The eruption reduced Tambora's lofty elevation to today's relatively paltry 9,350 feet — a significant drop in stature. It is thought that more than seventy thousand Indonesians perished as a result of the blast and its aftereffects, making it the deadliest volcanic eruption in history.

Despite the catastrophic effects of Tambora's eruption on Indonesia, the most long-lasting effect had little to do with its Hollywood-style pyrotechnics. Rather, it was the hundreds of millions of tons of sulfurous gas ejected into the stratosphere during the eruption. This, coupled with fine particles of ash blown high into the atmosphere, produced a haze that was seen as far away as London and New England. Although it resulted in some spectacular sunsets, its long-term effects were to be far more insidious.

As outlined in their fascinating book Volcano Weather: The Story of 1816. the Year Without a Summer, Henry and Elizabeth Stommel describe how the reduction in the sun's intensity caused by Tambora's stratospheric sulfurous belch created a global cooling effect the following year, 1816. The fact that the volcano was located practically on the equator made it easier for wind patterns to carry the effluent around the entire world, and the effect on the weather was pronounced. Amateur observers including several meteorologically-minded Ivy League scholars — who had been keeping careful records of daily temperature readings for many years — noticed a pronounced drop in June of that year. Local farmers saw the effects directly: a cold front that moved through New England between June 6 and 11 left several inches of snow on the ground as far south as Massachusetts and the Catskills of southern New York State, and a hard frost occurred in Pennsylvania and Connecticut. Two more frosts arrived in July and August, effectively destroying the New England corn harvest that season, despite attempts to replant after each cold front dissipated.

Things were even worse in Europe. An exceptionally cold and wet summer in 1816 battered wheat and corn crops in northern countries. The resulting famine contributed to a typhus epidemic in Ireland, and thousands died of hunger in Switzerland. France, having been defeated the year before at the Battle of Waterloo, erupted into riots over the high price of grain. Europe's problems would continue until the middle of the following year, when somewhat better temperatures allowed a harvest that was closer to normal. Overall, historians estimate that as many as 200,000 Europeans may have died as a result of the cold weather in 1816.

The local effects in Indonesia were far more extreme. The initial blast and pyroclastic flow on Sumbawa brings to mind that of Vesuvius in 79 CE, except far more powerful. As with Vesuvius, there even seems to have been a ‘Pompeii of the East’ that was buried underneath several meters of pyroclastic material. Furthermore, one of the villages lost in the blast spoke the westernmost Papuan language ever documented in the Indonesian archipelago — we only know of its existence because a small word list was compiled by Sir Stamford Raffles when he was Governor General of Java.

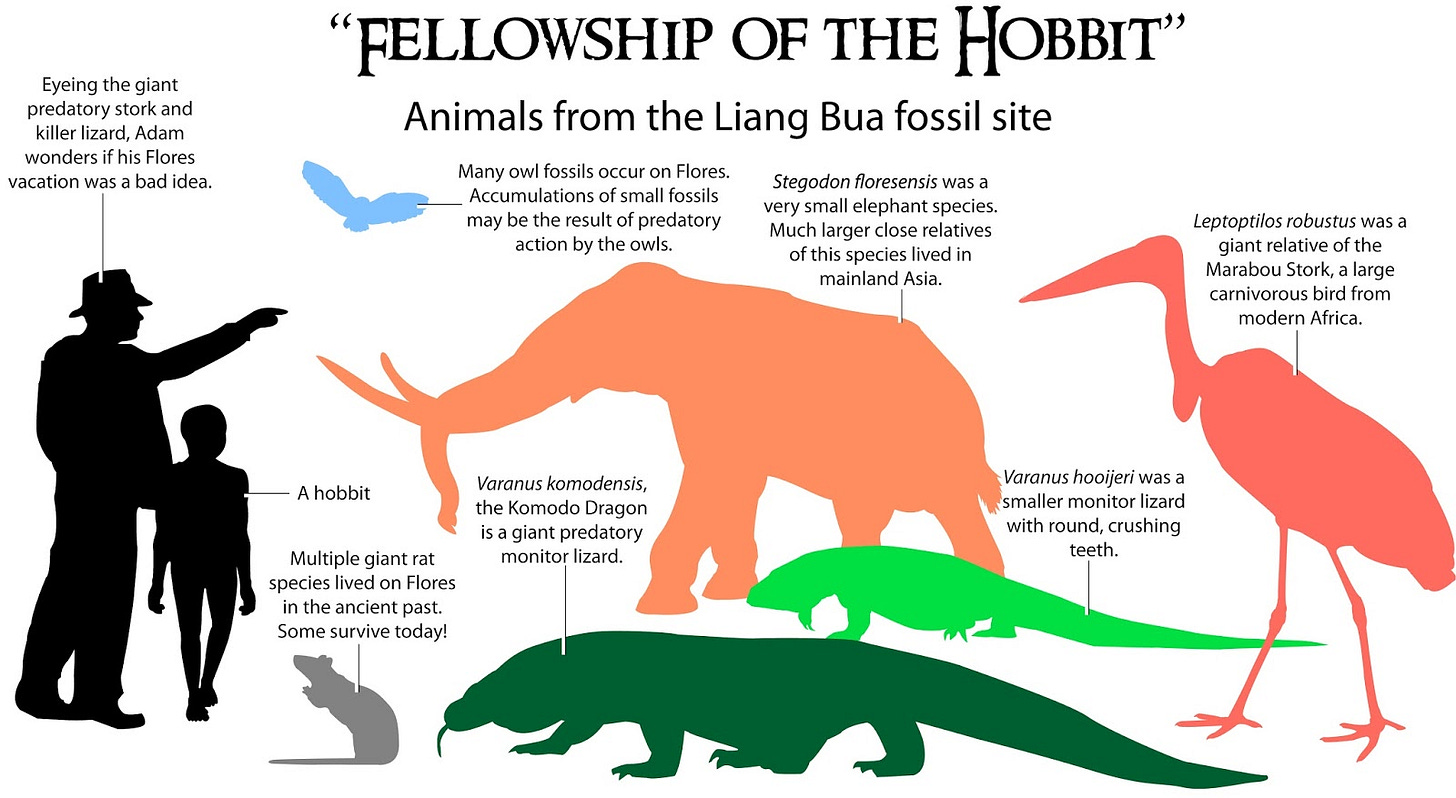

Some of the effects would have been more benign, but still quite extraordinary. Massive rafts of pumice entangled with tree stumps and branches clogged the Flores Sea for months afterward, disrupting maritime navigation. As large as 5km across, one was even spotted near Calcutta in the Bay of Bengal in October 1815. It’s interesting to speculate that huge rafts like these, riding the strong oceanic currents in eastern Indonesia, may have facilitated the migration of animal species between Wallacean islands. Could the Hobbits, or the diminutive Stegodon and giant rats they hunted, have hopped a ride to Flores on one of these at some point in the distant past — perhaps having been spurred to abandon their homes by an erupting volcano?

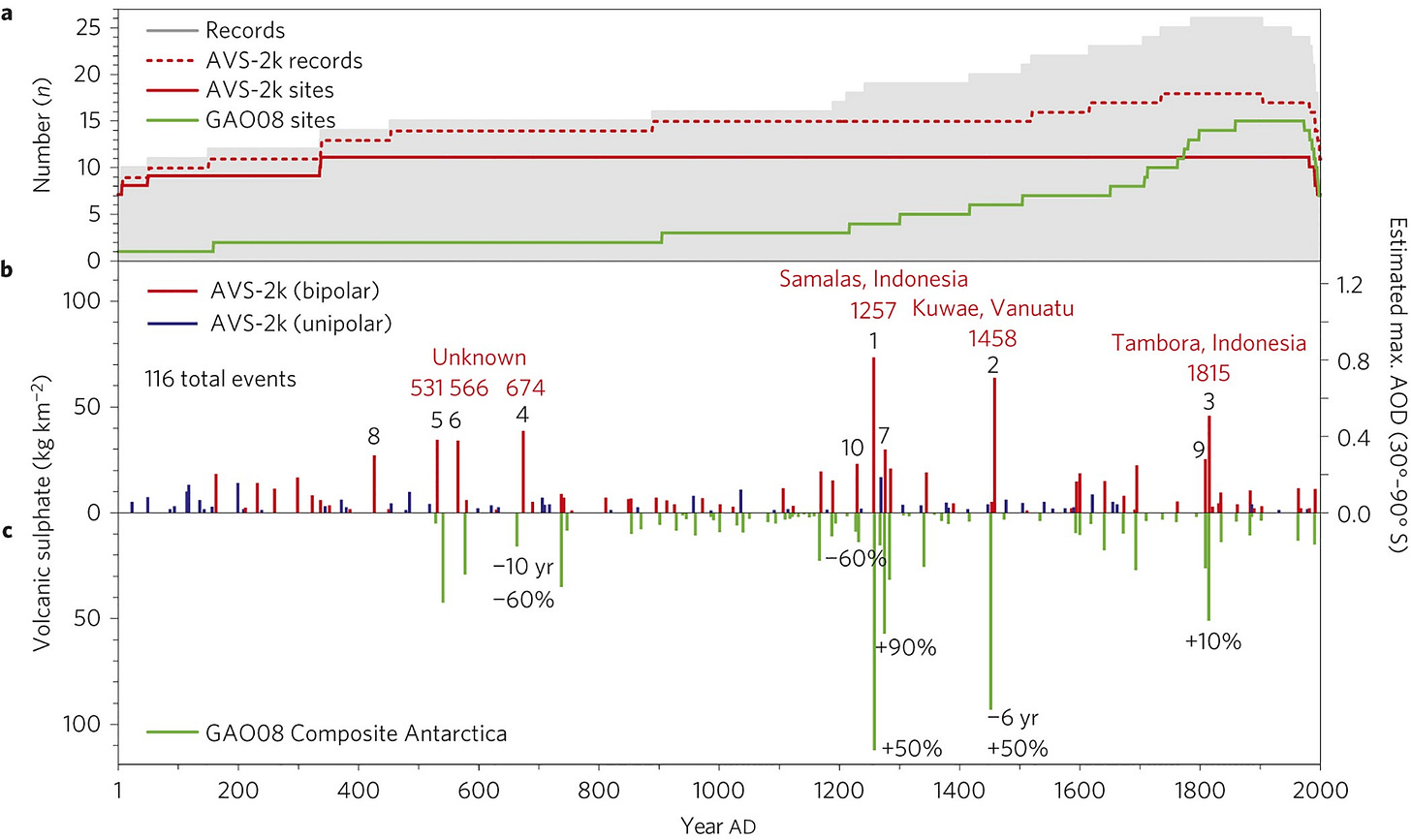

The scale of Tambora’s eruption is truly astounding — even more so, perhaps, because we now know that it wasn’t even the largest volcanic blowout of the past 1,000 years. That honor belongs to Samalas, the predecessor of today’s Mount Rinjani on nearby Lombok, literally in our own back yard. Rinjani/Samalas has erupted several times over the past century, but these have been relatively minor episodes of the sort that are fairly common in Indonesia. The last time it really blew up, though, was in 1257. How do we know this date with such precision? Through a fascinating synthesis of geological and historical information that has been pieced together over the past decade.

The sulfate signature has been known from ice cores collected in Greenland and Antarctica for many years — clearly a large volcanic eruption occurred around that time. Due to wind patterns, it must have been in the tropics to have dispersed its gases and ash worldwide. Apart from that, though, its identity remained a mystery until French volcanologist Franck Lavigne stumbled upon a medieval Indonesian manuscript written on palm leaves in Old Javanese, which described a massive eruption on Lombok in the middle of the 13th century that destroyed the island and its capital, Pamatan. Piecing these disparate souces together, along with studies of the pyroclasic flows on Lombok, Lavigne and his colleagues were able to confirm that Samalas was the culprit — arguably the largest volcanic eruption of the Holocene, and possibly the largest since Toba ~74kya.

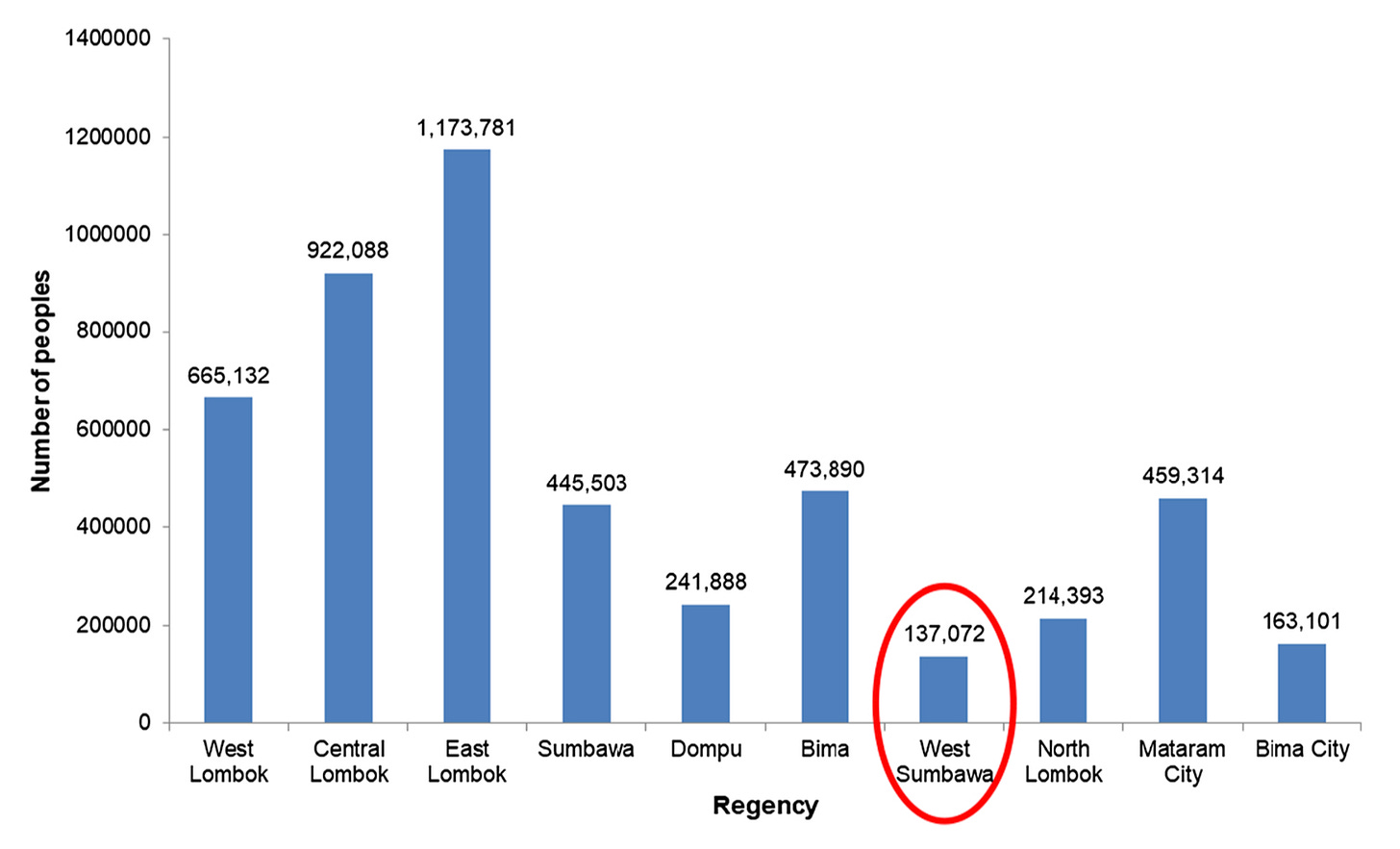

The location of Pamatan remains a mystery — this would certainly be the true ‘Pompeii of the East’ if discovered, especially since we know essentially nothing about the kingdom itself — but the legacy of Samalas lives on in the region today, according to Lavigne. In a 2021 paper he suggests that the reason western Sumbawa is depopulated relative to other parts of Sumbawa and Lombok is because of the perception that the land itself is cursed in some way due to the catstrophe. Especially as this perception would have been reinforced by the Tambora eruption, it certainly makes sense — and helps to explain the demographic patterns you see in the region today, especially driving through it rather than flying from city to city.

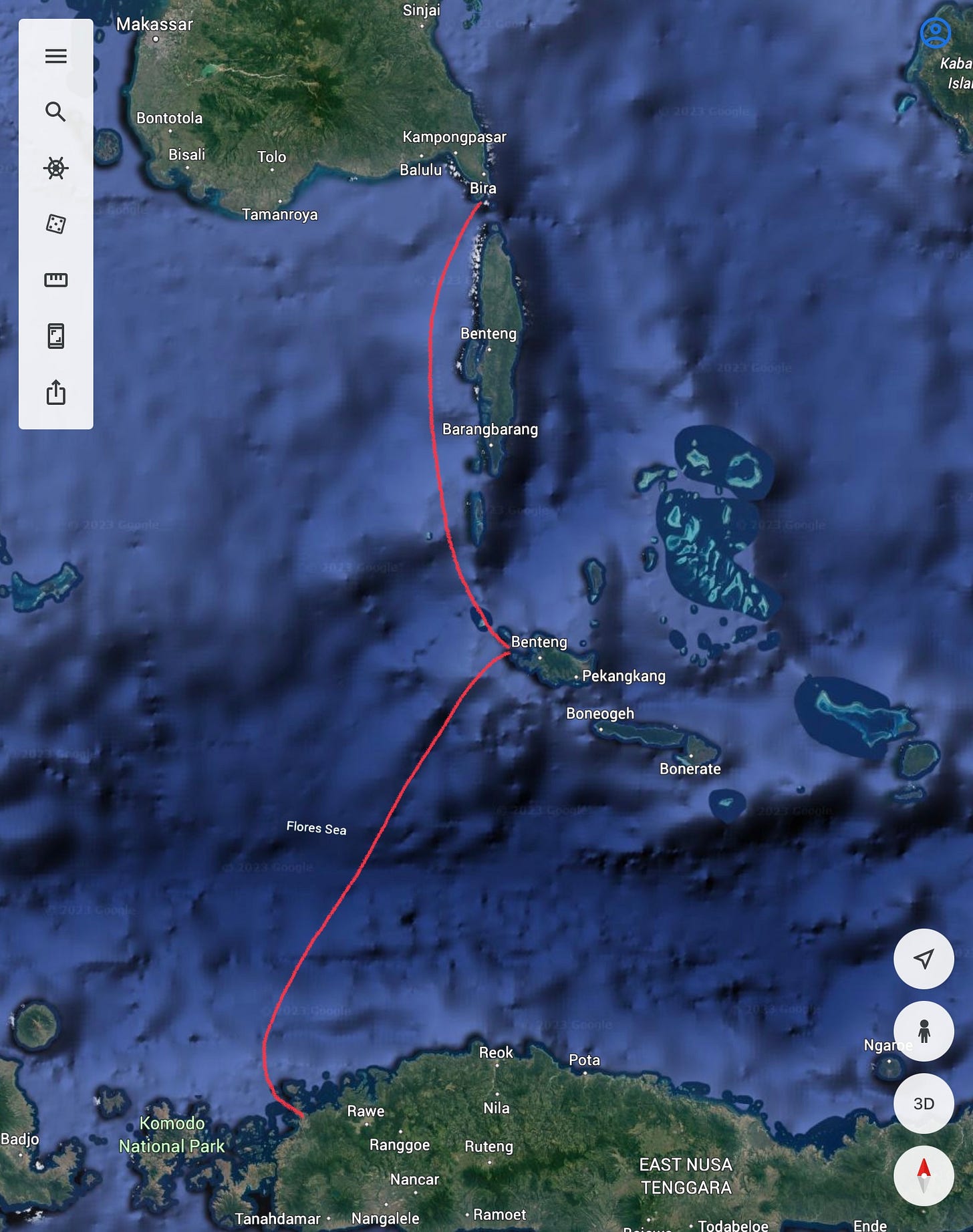

After resting for a couple of days at the Samawa Cottages, it was back on the road, pushing through to Bima for a quick overnight and then hopping the ferry to Labuan Bajo in western Flores. The drive took us past Saleh Bay, an enormous body of water on the north coast of Sumbawa enclosed by Moyo Island and Tambora to the north and east. This is one of the few locations in the world where a large population of whale sharks lives year-round, and along with climbing the Tambora caldera is one of the main tourist draws in the region.

The transition to eastern Sumbawa drove home how mountainous it is, a result of its tumultuous geological history. Essentially three huge volcanoes connected by ancient lava flows — Tambora, Oromboha and Diha, with a fourth, on the active volcanic island of Sangeang to the northeast, ready to join them soon — it made for a long, transmission-grinding drive to the port of Sape on the east coast.

Flores is famously home to the Hobbits, Homo floresiensis, which lived here up to ~50kya, as well as Komodo dragons — huge monitor lizards that have become gigantic on this unique island, with its mysterious evolutionary magic that makes species larger and smaller over time. Having visited both in March 2020, we left them in peace on this trip.

Now, having repaired a punctured tire and recovered from a foot injury sustained in Bima, swum in the Komodo Sea and relaxed on the beach while waiting for the weekly ferry to Sulawesi, it’s time to head off again on the ~30hr journey to Bira. Holly has flown back to Lombok, so I’ll be on my own until Makassar. Let the long voyage across the Flores Sea begin…